Good afternoon, and to make up for being out last week, here is an extra long post. This week’s theme is on some major trends that will define the future, with emphasis on geopolitics and technological development. For the former, I will discuss the work of Seán Cleary, executive vice-chair of the FutureWorld Foundation among numerous other achievements, and for the latter, that of Dale Buxton, an investor whose portfolio includes OpenAI, Formula E, and much else.

But before we get into that, I skipped my usual post last week because I was in Egypt for a reunion for a travel fellowship I did in 2014. The fellowship is East-West: The Art of Dialogue, an initiative of M. Shafik Gabr, who is the chairman of the ARTOC Group for Investment and Development. There is far too much to say about the fellowship to attempt to do so here. Seán and Dale were among the speakers this week. By way of disclaimer, since I am going from in-person presentations, I will try my best to represent their work accurately but do not guarantee success.

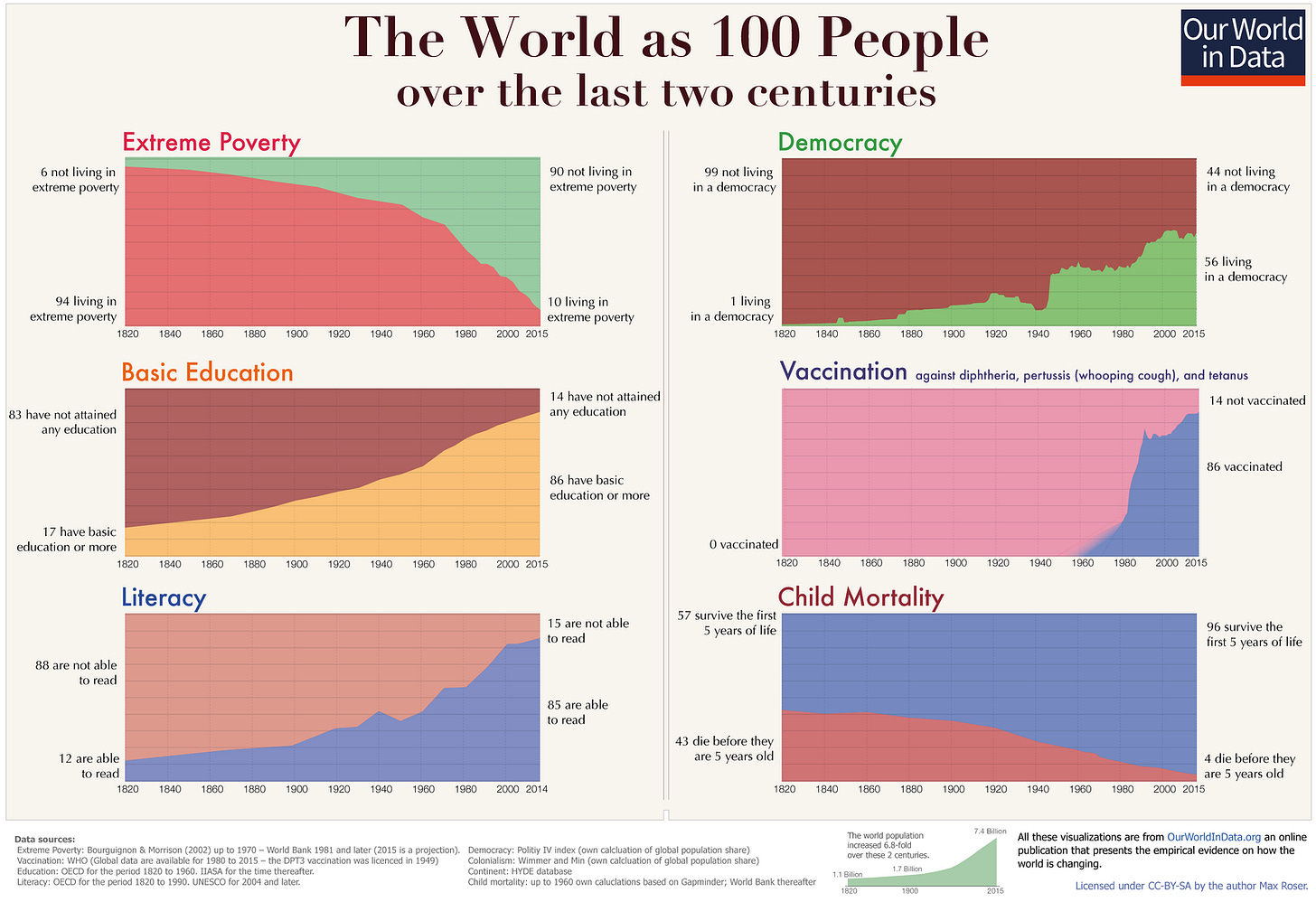

Seán’s presentation was entitled “Strategic Foresight in an Age of Disruption”. If there are ten houses on one’s street, and one of them is on fire, then it is very natural to pay more attention to the house than is burning than to the nine houses that are not. Likewise, when we consider geopolitics, it is natural to pay more attention to what is going wrong than what is going right. But this can give a distorted picture. For that, Seán opened with these important macrotends.

He emphases connectivity, including shipping, air travel, and Internet access, as vital factors that drive these trends. It must be emphasized that, while improving standards of living are long-standing world macrotrends, they are neither automatic nor inevitable. Good statecraft is about ensuring that these trends continue well into the future.

A major governance challenge is that there are three central priorities—global integration, national sovereignty, and democratic accountability—that exist in tension. On many important questions, it is necessary to recognize trade-offs. In Global Trends 2040, a work of the U.S. National Intelligence Council, much uncertainty at that date revolves around which priority will be dominant.

Seán spoke at length about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. While he and I would disagree on several points, we would agree that the invasion is a violation of the UN Charter, Article 2, that the invasion is morally indefensible and characterized by severe war crimes, and that it has been a serious strategic miscalculation for Russia.

Why Vladimir Putin thought this was the right decision will, I am sure, be discussed for many decades. Seán highlighted two factors: the expansion of NATO, about which I wrote last year, and the deployment of Aegis Ashore in Romania and Poland. Aegis Ashore, the land-based version of the ship-borne Aegis, is is a central component of American missile defense, about which I have written several times before. Russian leaders—not just Putin—clearly don’t like NATO expansion or U.S. missile defense. But I am more skeptical that these considerations played a significant role in the decision to attack Ukraine.

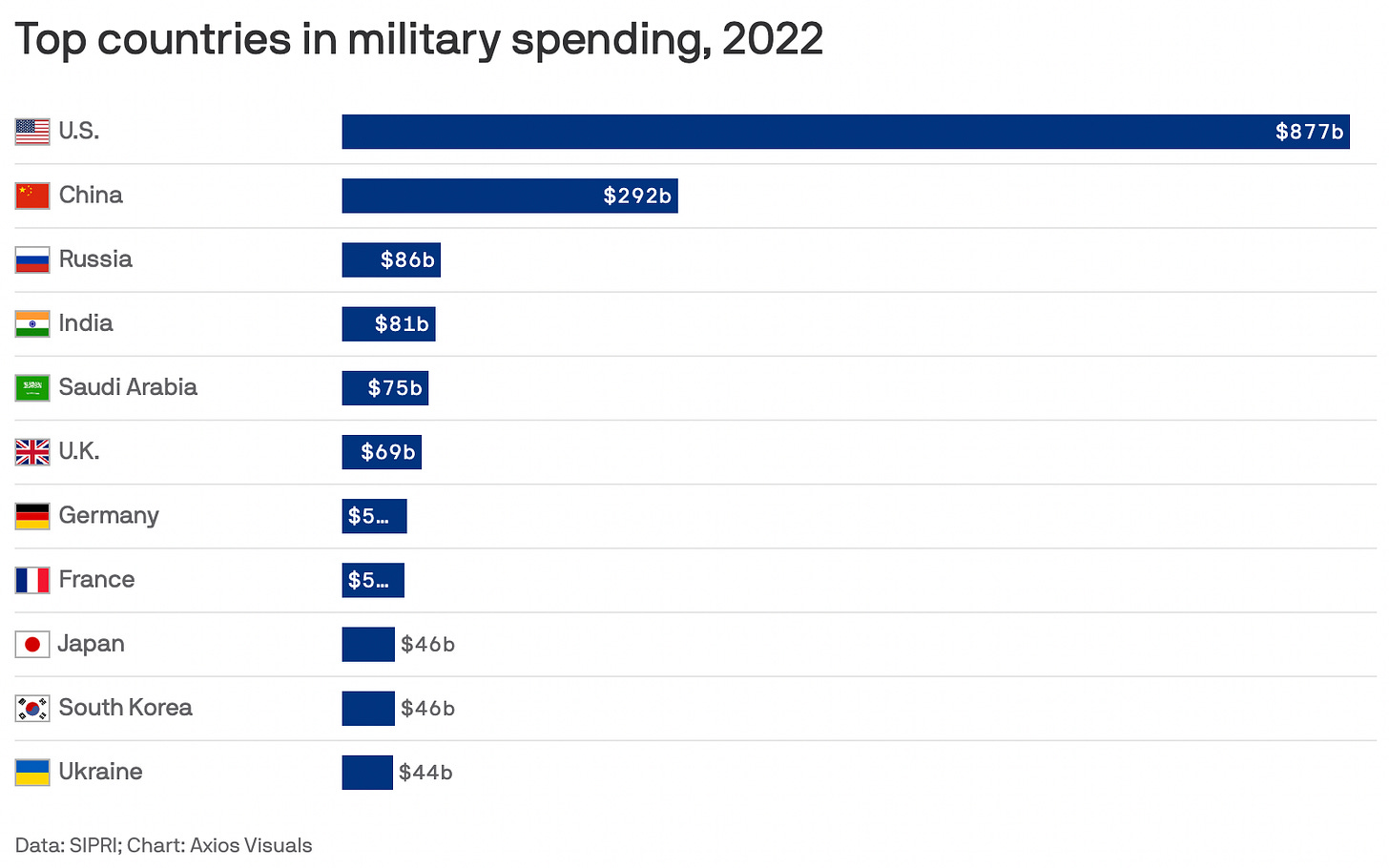

Broadly speaking, there are two schools of thoughts regarding foreign policy: realism and idealism, though I dislike these terms because they falsely imply that idealists aren’t canny and that realists are cynical and amoral. With caveats about the risk of oversimplification, I would characterize Seán as in the realistic camp and myself as in the idealist camp. For Seán, security rests in every nation, including Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Finland, and so forth, feeling that their security needs are met and in exercising a balance of power. In my view, security is best achieved when a single responsible power has disproportionate strength, which in today’s world would be the United States and allies—the Pax Americana vision. To illustrate that all sides can muster evidence, consider this on military spending from Seán’s presentation:

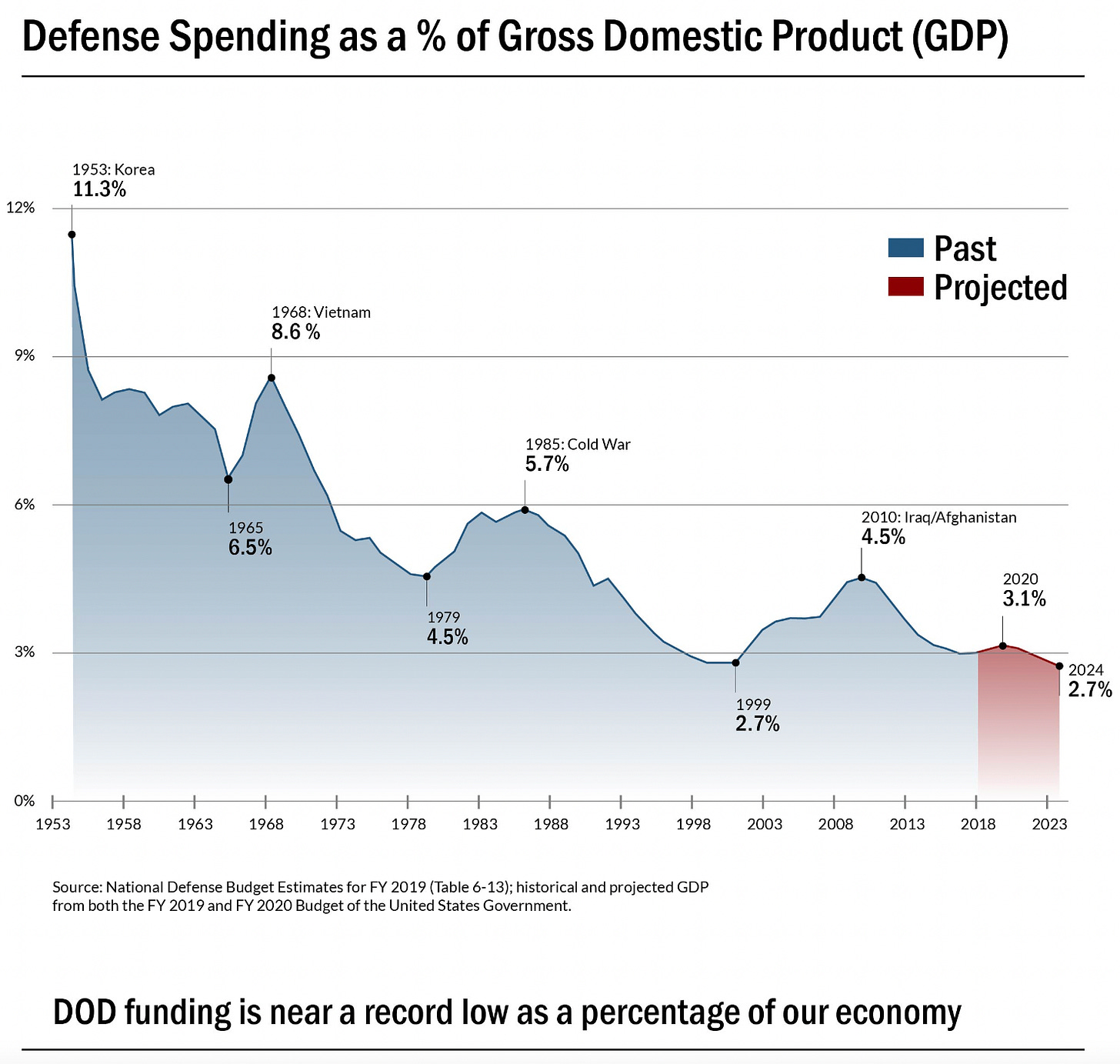

And a chart I prefer to highlight.

Two charts, both with accurate data (as far as I know), tell very different stories.

Seán discussed climate change as of great international importance. On that front, progress since the Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1997 has been disappointing. He also highlighted growing tensions between the United States and China. Here, while Americans have to acknowledge that we have real, well-based problems with the Chinese Communist Party, I see potential for positive engagement. China’s brokering of a restoration of relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran and their peace proposal in Ukraine are two recent positive moves.

The last few years have seen (supposed) democratic backsliding, a topic on which I wrote recently. Seán suggested that democracy, as we understand it now, is an institution of the Industrial Age, and that new institutions, perhaps such as a form of more direct democracy, may be appropriate for the current technological milieu.

I could say much more, but I want to move on to Dale’s presentation, entitled “World Changing Technologies for Good and Bad”. Before we get to specific technologies, Dale posited some general investment principles which I think are very important (my apologies for wonky formatting).

How Do I Choose Financial Investments

• Invest in what you understand or are willing to learn

• Look for companies that identify a need first before building a product or service (Hire a salesman first)

• Invest in people

• Look for leaders that inspire those around them

• Look for the crazy inventor leader that also has business sense or a strong partner in business

• Look for leadership that seeks to hire people smarter than themselves

The second point, “identify a need first before building a product or service”, is so important, yet I cannot say how many times I have seen people, including myself, fail to follow this principle.

Dale highlighted four world-changing technologies for the next five years: quantum computing, artificial intelligence, Internet of Things, and genomics.

Quantum computing is a computing paradigm that uses quantum superposition to speed up computation much faster than a classical computer could ever achieve. While quantum computing is not magic—NP-complete problems would remain unsolvable in polynomial time with a quantum computer barring an unexpected algorithmic breakthrough—a quantum speedup would enable many things such as drug and materials discovery, faster machine learning, and more. I wrote on quantum computing a few months ago. Dale is optimistic that commercially useful quantum computing will be available within the next five years. Others, such as Gil Kalai (my thesis grandadvisor), are skeptical that it can be done at all.

Quantum computing also poses a security risk by potentially being able to crack widely used cryptography algorithms. Efforts are ongoing to develop quantum-safe encryption. I suspect that the transition will be like Y2K or IPv6: it needs to be done, and because the problem is known well in advance, it will be done without major disruption. The level of risk depends greatly on how quickly fast quantum computers are developed.

Dale’s second trend, artificial intelligence, surely belongs on the list. There is a great deal of excitement around large language models, such as ChatGPT, image generators such as Dall-E 2 (with which I had some fun) and Midjourney, and many, many others. Those with a long memory will recall several waves of progress and disappointment with AI since the 1950s, and it is hard to predict how the current wave will develop.

Naturally, any discussion of AI must entail AI safety, and there was quite a bit. Dale stated that he regards the AI Pause to be a bad idea, on which I concur. Generally speaking I think that contemporary views on risks associated with AI are greatly overblown, but there are some and I would like to better address the topic later.

Internet of Things is a concept that appears to have passed the crest of the hype cycle and triggers plenty of (often well-deserved) cynicism. Growing pains aside, in my view, this is the one of Dale’s four areas that is now underhyped. I see IoT as a general platform integrating cloud robotics, neurotechnology such as Neuralink’s under-development brain-computer interface, and maybe even the dreaded semantic web, a vision now perhaps reincarnated as the latent web, to be developed with large language models.

As for genomics, the last few decades have been exciting for the advancements in biotechnology. However, despite (because of?) these advancements, the efficiency of drug discovery has been falling in a phenomenon known as Eroom’s law, as I discussed a few weeks ago. Unfortunately, due to time pressures, we had to speed through the discussion of IoT and genomics.

Dale had also planned to talk about access technologies (satellite constellations, cryptocurrency, remote job platforms), metaverse, nanotechnology, space, and ocean floor mapping, though these too were glossed over due to time limitations. Energy, especially deep-bore geothermal, advanced nuclear, and fusion is another important area that was not part of the presentation.

All this talk about technology raises an obvious question, known as the productivity paradox. How do we square the fact that we are apparently in an era of rapid technological advancement with the fact that productivity statistics, especially among wealthier countries, has been chronically disappointing? I know of no good answer to this, but I think the least bad answer is that technology is in fact having a significant effect on productivity, but that this effect is neutralized by factors such as population aging and regulatory sclerosis. I hope to address this topic more thoroughly later.

From my perspective, the most important common theme to Seán’s and Dale’s presentations is that there are many question marks about the future. Here my libertarian-ish instincts kick in. It would be folly to try to predict, let alone control, the future. But there are some timeless principles that we know will hold no matter what. One of them is the vital need to maintain dialogue, and for people of different cultures and experiences to find common ground rather than conflict. It is in this spirit that I am grateful to have gotten to know Seán and Dale last week, to have met or reconnected with the ~60 fellows at the reunion, and the opportunity to participate in this program.

Quick Hits

Michael Magoon’s YouTube Channel, From Poverty to Progress, documents how progress, defined particularly by rising standards of livings, came about. It would be worth checking out the book reviews and material on this channel.

The Risk Monger (David Zaruk) wrote about Greenpeace’s role in the recent Philippines Supreme Court case on golden rice. Criticizing Greenpeace is hardly sport nowadays, but the article highlights an interesting dynamic whereby activist organizations like Greenpeace are driven by the most ideological wings. Greenpeace had to pursue the cases against golden rice and Bt brinjal, lest the most strident activists would bolt and establish rival organizations, but they couldn’t celebrate their wins too loudly for fear of alienating everyone else. One recognizes a similar dynamic in many other legacy activist organizations, and I regret that by now, Greenpeace is too far gone to be salvaged.

Will sexbots cause further drops to fertility rates? This essay by Glenn Harlan Reynolds argues so. If Reynolds is right, then it would be another, less appreciated risk of AI development. I tend to think not, and that interest in sexbots, pornography, etc. is more of a symptom of the failure of family institutions than a cause, but I don’t know. One wonders how much farther the trend of falling birth rates can go before there is serious interest in widespread use of ectogenesis.

Caspian Report discusses (15 minutes) a leaked Russian document to annex Belarus by 2030. According to the video, the West may have missed an opportunity by sanctioning Belarus since the Russia/Ukraine War broke out to pull Belarus away from Russian influence and toward Western influence.

The Institute for the Study of War asserted that the recent drone attack against the Kremlin may have been a false flag operation. The truth is not yet firmly established, and ISW made a mistake in my view of putting forward speculation without solid evidence. Nathan Ruser wrote a thread on the damage that speculation causes. I rely heavily on ISW for my understanding of the war, and I hate to see that reliance thrown into question like this.

Also on the war, a few days ago Ukraine successfully shot down a Kinzhal hypersonic missile. This is, to my knowledge, the first successful interception of a hypersonic by any country, and it is encouraging news. Just a few days ago, the Congressional Research Service prepared a brief on hypersonic missile defense. But to throw some cold water on all this, Popular Mechanics ran an article suggesting that the Kinzhal is not all it is cracked up to be.

In my post two weeks ago on technological unemployment, it was an oversight not to discuss Karl Marx’s understanding of the centrality of automation to achieve the surpluses that will enable full communism. Contemporary leftists who are more technology-skeptical differ from Marx. A close analogue to Marx’s vision is Peter Joseph’s Zeitgeist Movement.

Unemployment in the United States is now at 3.4%, the lowest in decades. Productivity is down again this quarter and is doing historically badly. I don’t know if these trends can be pinned on population aging, but both are what one might expect from demographic trends.

Brian Clark’s story (47 minutes) of his escape from the 84th floor of the South Tower of the World Trade Center is most fascinating. He concludes with a personalized version of a lesson that I want to highlight for the world scale: we can and should set goals and make plans, but also recognize that our lives will ultimately be defined by the unexpected events.

Thanks for the shout-out for my YouTube channel. I appreciate it.