Thoughts for January 29, 2023

Good evening. Today’s topics are labor markets for the trades, AI and “real” art, democratic backsliding, and renter protection.

Labor Market for the Trades

In several past entries I’ve discussed some issues around the labor market and why I regard the idea of a widespread “labor shortage” to be false. Here I want to look at the market around building trades, and in particular, electricians. I think that trying to zero in on a particular profession will better help clarify the issue than trying to look at the market as a whole.

It is not difficult to find assertions of a labor shortage for electricians. This article is fairly typical. It comes from what I guess is an industry trade group. It asserts that there is a shortage of electricians for three reasons:

High rate of retirement.

Fewer entries into the field.

Rising demand.

So it gets the supply and demand factors right, or at least presents something that is plausible.

Here’s another article that asserts that there is a shortage of electricians, though it doesn’t offer much evidence. It’s an HVAC business in Pennsylvania, not a serious think tank, so at least I didn’t have high expectations. If you mosey over to the jobs page on the same site, you find

We are looking for certified technicians with:

3 Years Experience

Relevant licenses and certifications

…

This article claims that there is a stigma against the trades, which keeps the market perpetually undersupplied. The issue should be of concern to climate hawks as well, since electrification is viewed as a major part of the pathway to reducing emissions, and electrification will be hampered by a tight workforce.

The basic problem with the labor shortage idea, which I’ve discussed before, applies in this context as well. “Shortage” is subjective. In a reasonably free market, if a shortage emerges in a particular market, the price should arise, attracting greater supply and reduced demand and bringing the market back into equilibrium. The Border States article linked above asserts that this shortage has persisted for at least two decades, more than enough time for this process to occur. And so an explanation for why this doesn’t happen is needed.

First, regarding salary. I put this together quickly and was not able to find proper statistics in a reasonable time, but consider that from 2004 to 2021, median wages in the United States (nominal) increased 56% from 2004 to 2021, while the average federal salary for electricians increased 37% from 2004 to 2021. Yes, these are electricians employed by the federal government, not the job market as a whole, and we’re comparing average with median, but I find it to be more than enough to cast doubt on the idea that electrician salaries are rising faster than salaries as a whole, which is what one would expect in the event of a labor shortage.

The second fishy point relates to occupational licensing. This is a big, complex issue that I cannot adequately discuss today. Occupational licensing has emerged as a major concern in recent years. Here’s a 2015 Brookings article on the subject. Electricians are one of the most heavily licensed professions, and this article, though critical of the growth of licensing in general, seems to endorse strict licensing for electricians.

A study commissioned by the BLS found that electrician occupational licensing generally grew more stringent from 1992 to 2007. I’d be curious to see if these trends persist with more recent data. On the subject of safety, ostensibly the purpose of licensing, the study finds

Finally, the results obtained for the incidence of injury and death and for the severity of injury rates and death rates show that the impact of occupational regulation on deaths and injuries is statistically insignificant or indeterminate in the multivariate analysis.

Most studies, as well as common sense, suggest that licensing should raise salaries by reducing the labor supply, though this study claims otherwise for electricians and some other professions. If there was a really a labor shortage among electricians, one would expect more pressure to reduce occupational licensing restrictions, especially given the lack of evidence that they actually help with safety.

Far be it for me to be cynical, but what I suspect is going on here is that trade organizations are hyping up the idea of a labor shortage because they want more public money for trade schools.

AI and “Real” Art

There is much hype right about about large language models (e.g. GPT-3, ChatGPT) and generative content (e.g. Dall-E 2, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney), prompting much discussion in the popular press that would benefit from historical context. There are plenty of issues to consider; today will be the question of whether art generated with the aid of deep learning should be consider legitimate art.

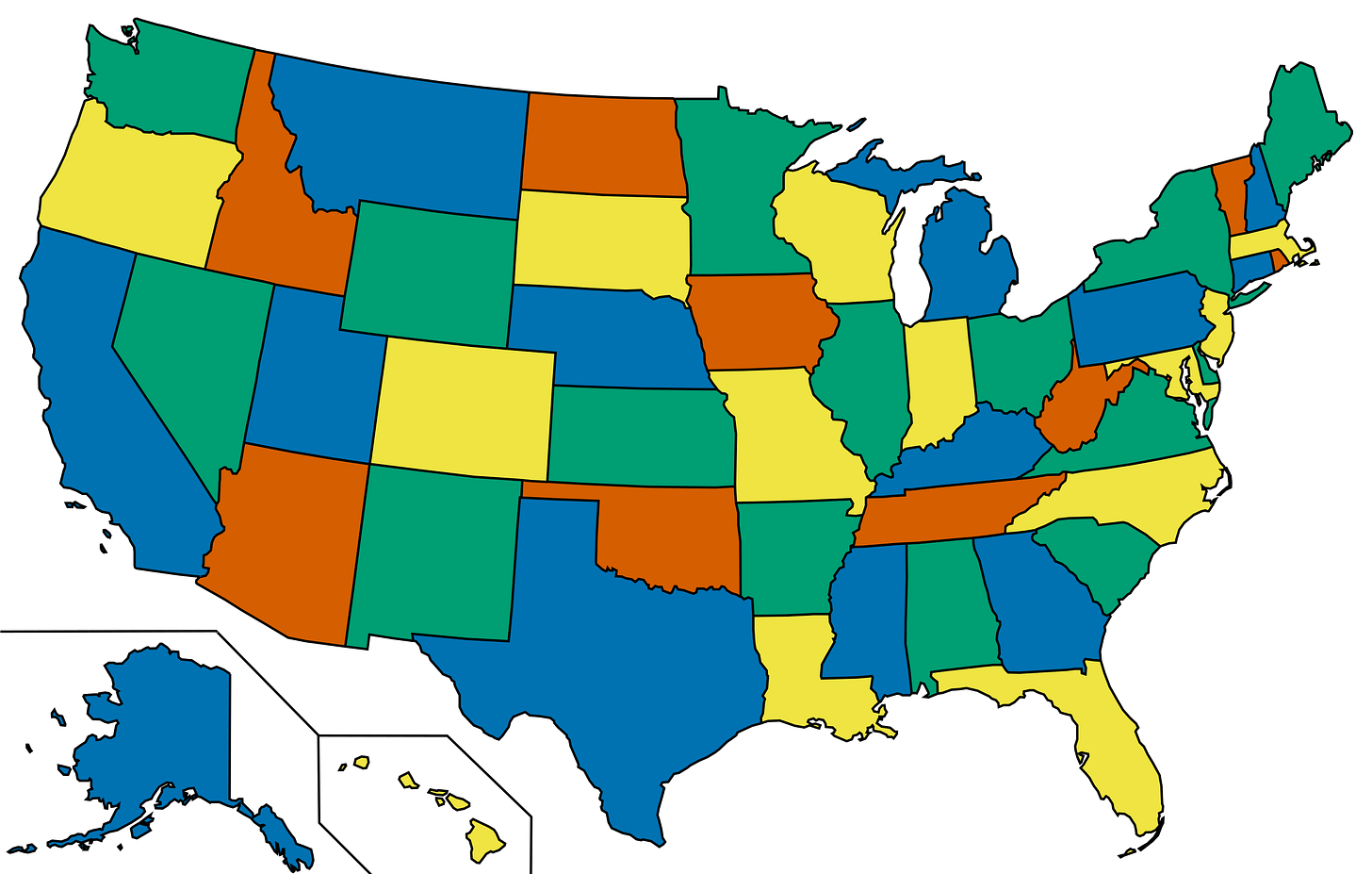

A relevant context comes from the four-color theorem. In graph theory, the four-color problem is the question of, given a planar graph, is it possible to assign colors to the vertices, from a set of four colors, so that no two vertices that share an edge are assigned the same color?

The four-color problem was outstanding for a long time until proven by Appel and Haken in 1976. Some errors were alleged in the original proof, and Appel and Haken corrected them later. Georges Gonthier has since formalized the proof for the Coq theorem prover, and so the theorem is now as established as we trust the Coq kernel. Robin Wilson tells the story in this book.

Aside from being an interesting, if not terribly useful, mathematical result, the four-color theorem is notable for being the first major theorem to be proven with a computer. The nature of Appel and Haken’s proof involved so many distinct cases that they could not feasibly be checked by hand. As explained by Wilson, many mathematicians in 1976 felt uneasy that a proof reliant on computer code was “legitimate”, and it didn’t meet the standard of elegance and simplicity that most mathematicians, then and now, look for. By the time I was in graduate school (2004-2010), the controversy around computer-assisted proofs had disappeared, and I didn’t understand what the fuss was about. I still don’t.

The implicit (now to be explicit) purpose of reviewing this anecdote is to wonder if doubts about AI-generated art are driven by fear of the unknown, to be dispelled once tools such as Dall-E 2 become established. I suspect that this will be the case.

Democratic Backsliding

A few months ago, I wrote about trends in democratic backsliding, or the democratic recession, based on the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) data set and Freedom House. I asserted that, while different data sets differ somewhat on the democratic status of a nation, they all paint the same picture of a rollback in democratization that began some time around 2007.

But this paper argues otherwise. The problem, argue the authors, is that V-Dem and Freedom House rely on expert coding to determine various points of democratic status, coding which may be subject to bias. Instead they attempt to measure democratization through entirely objective data. The measures they use are

How often do incumbents lose elections?

To what extent are elections contested in a multiparty setting?

How often is the party of the executive also the party of the majority of legislators?

How competitive are elections?

How often do executives attempt to evade term limits, and how often are they successful?

How many journalists are jailed and murdered in the line of duty?

Among these metrics, journalists being jailed is the only one which shows a clear bad trend. For all others, the trend is either flat or improving.

Why the divergence between these objective metrics and subjective coding? It could be that coders bring biases to the table, including a subtle raising of standards that makes it look like there is backsliding. It could also be that there is genuine democratic backsliding that is captured by the coders but not by the objective metrics. This paper will surely not be the last word on the subject.

Renter Protection

The White House recently released some new actions on renter protections. Major items include some anti-discrimination provisions and rent control (er, “limits on egregious rent increases”) for public and subsidized properties. The follows a fairly modest set of proposals last year to increase the supply of housing, particularly subsidized housing.

Pro-housing advocacy generally falls into the following categories, or some combination thereof: increase supply through liberalizing zoning and streamlining processes; renter protections, including rent control; and more money for subsidized housing. Advocates of the various approaches are often in conflict with each other.

Diane Yentel wrote this in enthusiasm for the new renter protections. She heads the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which advocates for the second and third of the housing approaches. On increasing supply, the NLIHC wrote a report that contains the following dismissive remarks about filtering, or the idea that the construction of expensive housing will improve affordability for all income groups.

Yet in fact the filtering process fails to produce a sufficient supply of rental homes inexpensive enough to be affordable to the lowest-income renters. In strong markets, owners have an incentive to redevelop their properties to justify asking for higher rents from higher-income households. In weaker markets, owners have an incentive to abandon their rental properties or convert them to other uses when rental income is too low to cover basic operating costs and maintenance.

But in another blog post, the NLIHC made some tepid remarks that seem to favor allowing more market-rate housing. It’s probably fair to characterize the NLIHC’s position toward zoning reform as favorably disposed, but outside of their areas of interest. As will quickly be observed with any involvement with municipal housing politics, many low-income housing advocates opposed market rate development.

I think it is fairly obvious that there cannot be a solution for housing affordability without increasing supply. Renter protections, rent control, and subsidies, without increasing supply, simply shuffle the problem from one group of people to another. Then why the opposition, or at best indifference, from most groups? It would be easy to point to the Shirky Principle, the idea that institutions attempt to preserve the problem which they were created to solve. It would be foolish for a pro-housing group, which derive their raison d'être from the shortage, to alleviate that shortage and undermine the source of their funding and influence.

But I’ll offer a slightly less cynical explanation. Over the decades, there have been numerous efforts to relax zoning restrictions that constrict supply. Federal efforts go at least as far back as HUD, under Jack Kemp, trying to roll back zoning rules and NIMBY opposition to affordable housing. Yet the problem continues to get worse, seemingly without interruption. Advocates such as Yentel may have concluded that mere symbolic actions are the best possible. And they may very well be right.