Thoughts for September 11, 2022

Good afternoon. Today’s topics are democracy trends, the EU energy crisis, ecologism, and space migration.

Democratization

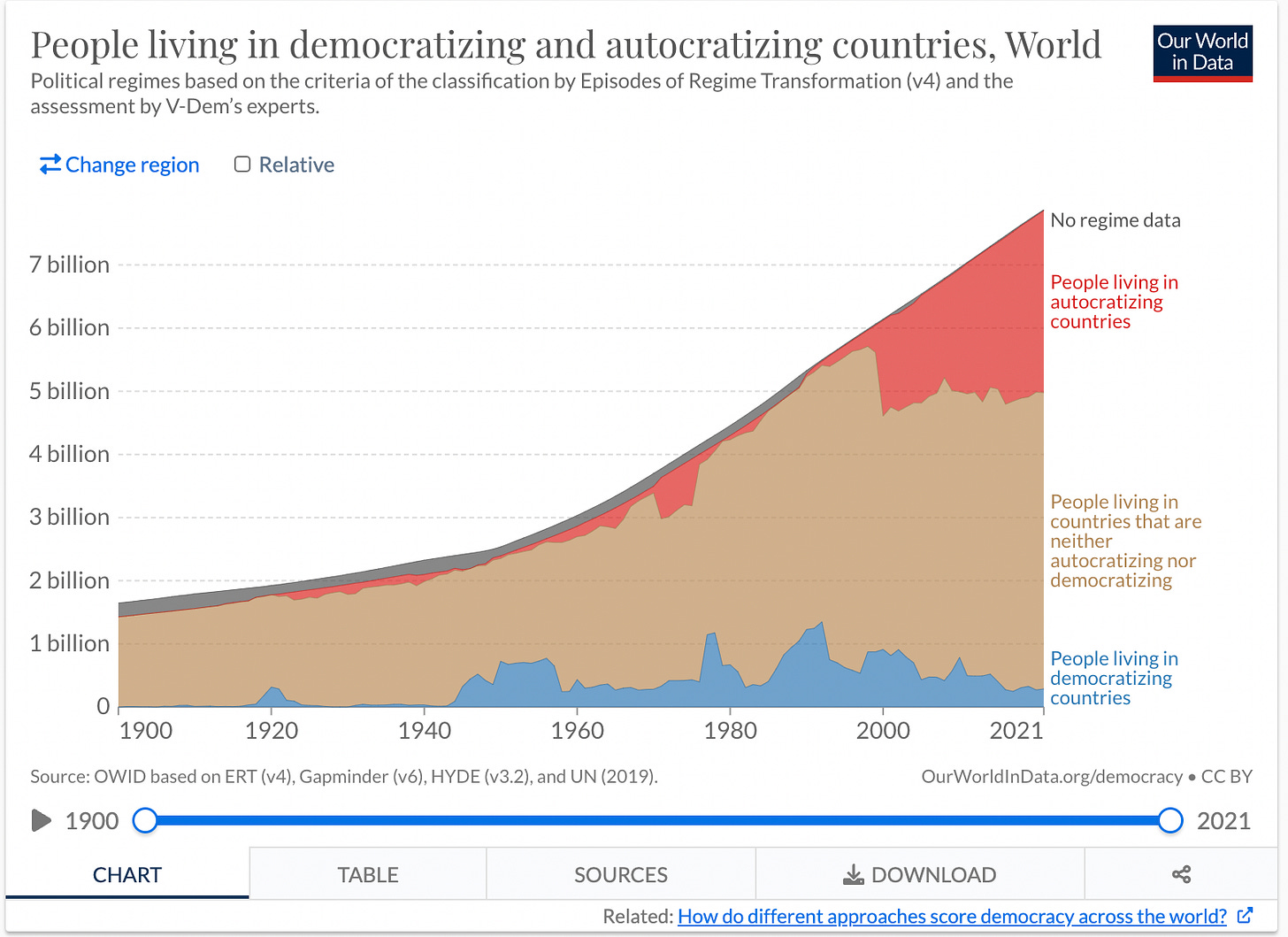

Our World in Data has a new article on the “democratic recession” of recent years. They rely heavily on the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) data set.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the concept of democracy, its sometimes abuse in political discourse, and in particular the problems with the Freedom House data set, which is often used to measure democratization. But the V-Dem data set, as well as others that the OWID articles refers to, all paint similar pictures.

One observes periods of autocratization in the 1930s and 1970s, which were followed by periods of democratization. But the current wave of autocratization looks to be more severe and more durable, even when accounting for population growth. According to V-Dem, overall world democracy level is now back to 1989 levels. OWID takes pains to emphasize the long-term democratization trend, and it implies that like past autocratization waves, the current wave will be temporary and in time we will see the world reach new heights of democracy.

In American political discourse, I notice a growing willingness to discuss nondemocratic political arrangements. Such views are still minority views, and they are driven mainly by factions that are frustrated at their inability to attain power through the electoral process.

One factor that makes the V-Dem data set look worse than the reality actually is is that the rate of autocratization in recent years is generally slower than pre-1994 episodes. We have a Cold War-era image of autocratization looking like a military strongman launching a coup and establishing a dictatorship. While that has happened in a few instances recently, such as in Myanmar, most of V-Dem’s autocratization is of the form of democratically-elected rulers proceeding to weaken institutions such as an independent media, the rule of law, an independent judiciary, civil rights, etc., such as we have seen in Hungary, Brazil, India, Poland, Serbia, and Turkey. Would-be autocrats cannot move too quickly, for fear of triggering domestic or international backlash.

The above-linked article, and this paper by the same authors, emphasize that there is plenty of room for trends to change. They identify a wave of autocratization shortly after Francis Fukuyama declared an “end of history”, in which liberal democracies would permanently be the normal form of government. They argue that declaring an “end of democracy” would be equally premature.

The characterization above notwithstanding, there were five military coups (Chad, Guinea, Mali, Myanmar, and the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan) and one self-coup (Tunisia) in 2021, much greater than the recent average of 1.2 coups per year. This suggests that autocrats may be becoming bolder.

It isn’t clear to me why this trend is happening. As outlined here, the story of democratic backsliding is different in different countries, but I haven’t yet seen an accounting for the global trend, though it isn’t hard to notice a severe aimlessness in the leadership of many democratic countries and international institutions. Still, whatever the shortcomings are to liberal democracy, there is no alternative that has demonstrated that it can deliver long-term prosperity.

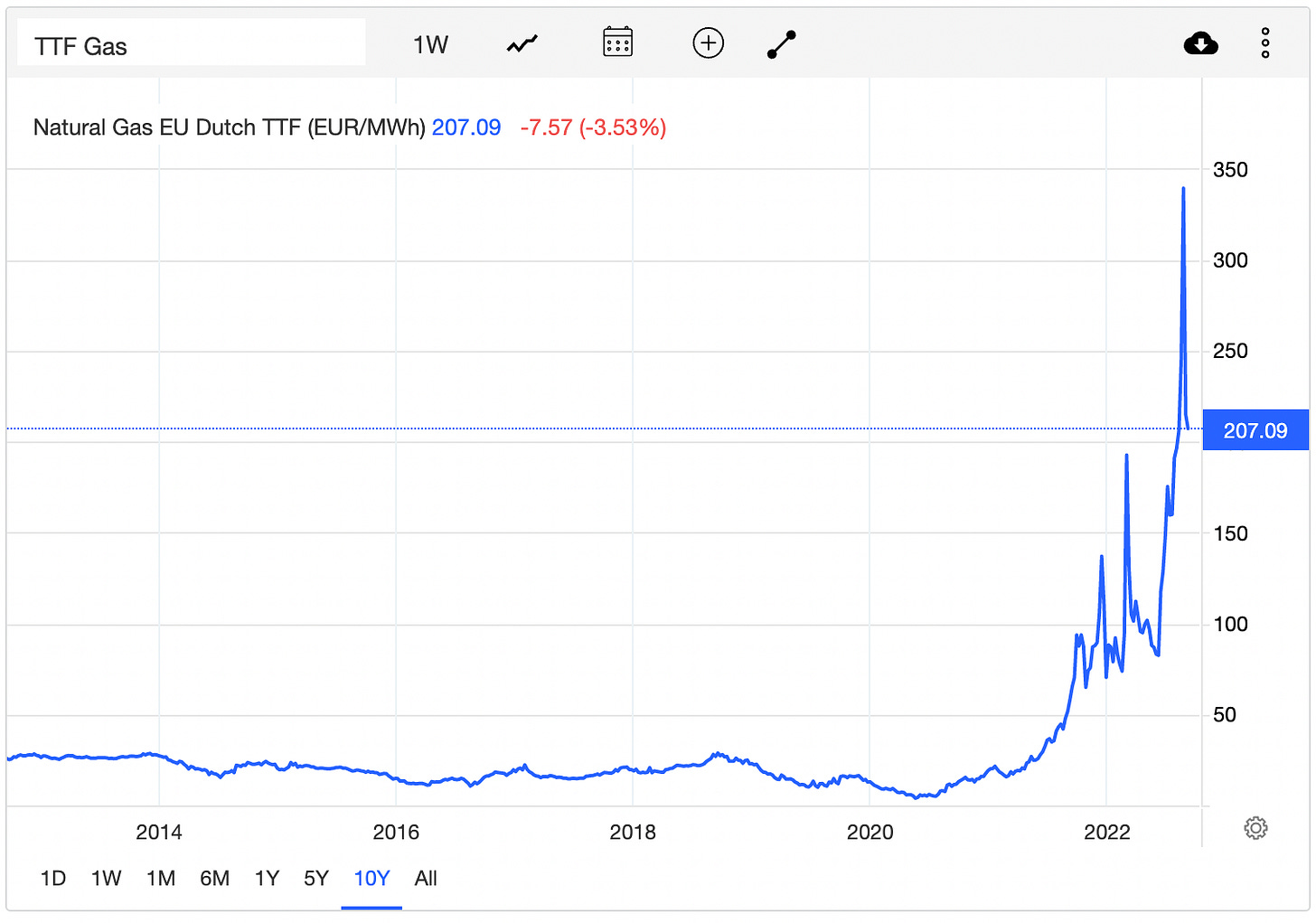

EU Energy Crisis

The European Union is in the midst of a severe energy crunch. The proximate cause for this crunch is the dispute with Russia over natural gas supplies, but the problems have been building for years.

In 2011, Germany made a decision to shut down their remaining nuclear power plants, and the energy crisis has not compelled them to reverse that decision. The rest of the EU is frustrated at Germany’s refusal to change course. So committed is Germany to shutting down the nuclear plants that they instead reopened some coal plants this summer to address the energy crunch. Though it does look like they have finally decided to extend the operation of two of the plants by a few months (article in German).

Europe has abundant natural gas supplies, but France, Germany, and several other European countries have banned hydraulic fracturing, and elsewhere fracking is stymied by protesters, taxes, and regulation. While these bans were instituted for ostensibly environmental reasons, the comparative environmental impact of burning coal, or importing gas from Russia and financing their wars of aggression, were evidently not considered. Russian support of these anti-fracking movements has long been understood. For their pro-Russia energy policies, the German Greens have been rewarded with a surge at the polls.

Thus the European energy crisis should be understood as a self-inflicted crisis, not the result of any genuine limitations on available supply.

Energy is foundational to economic health. However, it could be that an extended period of prosperity has brought Europe, and Germany in particular, into a state of complacency about the importance of energy, leading them to neglect their supplies and security. This thread paints a chilling picture of how the crisis, left unaddressed, threatens Germany’s status as a prosperous country. Extended high energy prices could devastate the country’s manufacturing sector, the main source of the country’s wealth. This, together with the political imperative of subsidizing energy for consumers, could end Germany’s ability to finance the arts, higher education, and other priorities. Once they have lost their manufacturing base and talent, it will take generations to rebuild, and by the time the political leadership is finally compelled to change course, it is too late. You might say, “Germany’s political class wouldn’t do something so foolish”, but if they were in a habit of governing responsibility, the country wouldn’t be in such a fix to begin with.

Success of the Degrowth Movement

In the first half of the 20th century, two major ideologies emerged to challenge liberal democracy: fascism and communism. Following World War II, fascism was too discredited to remain a major ideology, and by the Brezhnev era in the Soviet Union, communism had ceased to have major ideological power.

In the second half of the 20th century and so far in the 21st, environmentalism is the one major ideology to emerge and have significant worldwide policy impacts. But not just environmentalism, but a particular strand of environmentalism that has been termed ecologism. Ecologism has two major distinct but related planks.

The non-human world merits moral consideration independently of its utility to humans.

Degrowth—a deliberate lowering of gross domestic product—and population control.

(Ecologic ideas have roots as far back as the Classical period, and they were prominent in 19th century Romanticism. Almost all ideas have origins far earlier than you first realize.)

While there hasn’t been an example of what I would call a genuinely ecologic government, in the way that there have been fascist and communist governments, ecologism has made significant inroads into governance. Examples include Sri Lanka’s recent experiment with organic agriculture, Germany’s energy policies as described above, China’s One Child Policy, forced sterilization in India, among many others that could be cited. Ecologic thinking has also become central to a large number of NGOs that operate internationally and transnational institutions such as the International Energy Agency.

Some critics write off degrowth as an unworkable idea that will never attain political influence. Only the first half of this assessment is correct. It would be a mistake to be so dismissive.

One can imagine alternate histories. In our timeline, ideas such as Julian Simon’s The Ultimate Resource, whose title refers to human ingenuity, have not gained traction in mainstream environmentalism. Perhaps in an alternative universe, such views constitute mainstream environmentalism, and anti-capitalism and degrowth occupy anti-environmental niches.

Space Migration

A few days ago, Human Space Program published an editorial I wrote on the need to approach space migration with urgency. Go read it there; I won’t rehash the points here. And while you’re at it, HSP publishes weekly by different authors that are worth taking a look at.