Thoughts for April 10, 2022

Good afternoon. Today’s topics include direct air capture, congestion pricing, and NATO expansion.

Direct Air Capture

The International Energy Agency issued a report recently on direct air capture (DAC). DAC is a technology that remove carbon dioxide from the ambient atmosphere, and it is one of several carbon dioxide removal (CDR) tools on the table. It differs from ordinary carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) in that it operates on the ambient atmosphere rather than a concentrated industrial waste stream. Since the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is much lower than a waste stream, DAC is more expensive and energy intensive than most others forms of CCS.

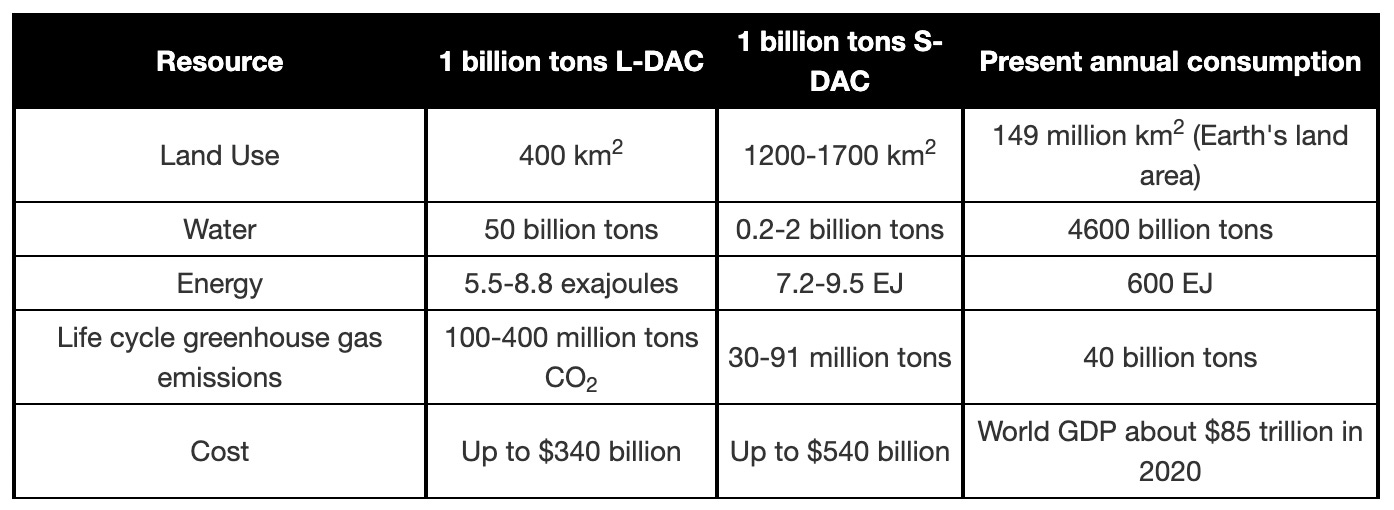

There is a minuscule amount of DAC today, but it appears that the technology is at an inflection point and poised to take off. The IEA estimates that we could see 980 million tons of CO2 removed by DAC every year by 2050. This contrasts to present world emissions of about 40 billion tons per year of CO2, plus a bit more methane, nitrous oxide, and other greenhouse gases. Based on the report’s numbers, here is what would go into removing a billion tons per year.

Under the L-DAC route, water usage could be an issue. The report estimates that if an L-DAC facility had to desalinate its own water, that would add $3.50-9.50/ton to the cost of CO2 removal.

The report estimates that with more maturity, the cost of DAC should go lower than $100/ton. This would put it in line with other established carbon mitigation measures and the social cost of carbon, albeit on the more expensive end of both. But DAC is appealing because its potential is effectively unlimited, creating an affordable backstop on the price of CO2 emissions, much as desalination is a backstop on water shortages even if not used widely.

A side note about geological storage. Captured CO2, whether from DAC or from more traditional CCS methods, can be used for products such as synfuels or stored in caverns. The potential for storage is hundreds, if not thousands, of years of CO2 emissions at present rates, so there is no concern about there being enough. The leakage rate is estimated at less than 0.01% per year, which should make geological storage secure over relevant time scales.

As a carbon mitigation tool, DAC will be more expensive than other carbon offsets for the foreseeable future. But traditional carbon offsets have several problems that raise doubts about their effectiveness. These problems include

How durable are offsets? Afforestation is only good until the next forest fire.

For conservation offsets, was there a risk that the plot of land would have been developed anyway? Probably not if it was cheap to acquire.

If it would have been developed, does the offset simply move development to another site?

DAC doesn’t have these problems, and it offers us confidence that actual CO2 removed will be as advertised.

Congestion Pricing

It is impossible to complain about traffic without being part of the problem. In economics-speak, traffic congestion is an externality, meaning that a driver imposes this cost of other drivers and doesn’t ordinarily account for it in driving decisions. Congestion pricing is a system that uses tolls to internalize this cost. It differs from ordinary road tolling in that the purpose is to manage congestion, as opposed to finance roads or other purposes, though functionally the two may be similar.

There are several congestion pricing systems in the world. The earliest, and arguably the most developed, is Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing system. There are also notable systems in London, Stockholm, and other places.

Designing an effective congestion pricing system is quite challenging. Oregon Metro, the government body behind the (Oregon-side) Portland Metro area, is in the early stages of studying and possibly developing and implementing congestion pricing. They are still working on basic questions, such as whether to implement a cordon (a charge is assessed for driving in and/or out of a designated area) or tolling certain roads.

Needless to say, congestion pricing is politically difficult, which is why so few cities have done it so far. Congestion pricing is often perceived as regressive, in that low-income citizens pay a higher share of their income; this perception is accurate according to an OECD report. Congestion pricing, as with market rate parking pricing discussed last week, is often seen, with some justification, as an anti-automobile measure, even though it doesn’t have to be. Nevertheless, as also discussed in the aforementioned OECD report, congestion pricing usually becomes popular once it is established. Maybe what is required is far-sighted politicians who are willing to take a short-term hit for long-term benefits.

NATO Expansion

Bill Clinton had an interesting editorial this week, defending his policy of NATO expansion. This policy has come under the microscope in recent months as having possibly inflamed Russian nationalism and contributed to the grievances that are behind the war.

Clinton presents his stance toward Russia as having two goals: first, to insure good relations, which were very much in doubt in the aftermath of the Cold War, and second, to insure European security in the event that the first goal failed. NATO expansion was very much in line with the second of these goals. Had NATO not expanded after the Cold War, or even dissolved as some strategists argued for, Europe would be much less secure against Russian aggression than it is now.

The historical analogy might be overdone, but aspects of the debate around NATO expansion are reminiscent of the debate about whether the punitive aspects of the Treaty of Versailles, especially the War Guilt clause, inflamed German nationalism in the interwar period and were among the grievances that led to Hitler’s rise and World War II. History has not been very kind to Versailles; see this post for a decent overview of the subject.

Still, to any “but what about Russia’s security interests?” comment, I would counter with the security interests of Eastern European NATO members. No country was compelled to join NATO against their will; expansion occurred just as much because former Warsaw Pact countries and Soviet Republics wanted to join as that older NATO members were willing to have them.