April 22, 2023: Technological Unemployment

Good afternoon. Welcome to the new readers, of which there are quite a few this week. Every week, I write about a few topics that are of interest to me, though I am experimenting with focusing on one major topic per week and a few smaller topics. This week’s main topic is technological unemployment, or the idea that the world may face severe, chronic unemployment as a result of technologies that can automate most work. Also, I will be traveling next week and am not planning a post.

Technological Unemployment

Fears of technological unemployment, or the idea that advancing technology could render large shares of the workforce obsolete, go back to the ancient world. And yet, after centuries of innovation, the unemployment rate in the United States stands at 3.5% as of March 2023. It would be easy to write about how technological unemployment is as irrational a fear as that of ghosts, though that is not quite what I will do here.

In the 19th century, when economics as a science came to maturity, the dominant, though by no means universal, view was that unemployment resulting from innovation should be only a temporary phenomenon, and full employment should return after a period of adjustment. The notion that economic production should be a function of productive capacity, and that demand is virtually unlimited and would follow from production, was formalized by Jean-Baptiste Say in Say’s law. Prominent dissenters from this view include David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx.

The fear gained more traction with the Great Depression, during which the co-occurrence of high unemployment, idled factory capacity, and poverty challenged Say’s law and other established dogmas of economics. Even before the stock market crash of 1929, chronic rural unemployment in the United States was a serious problem.

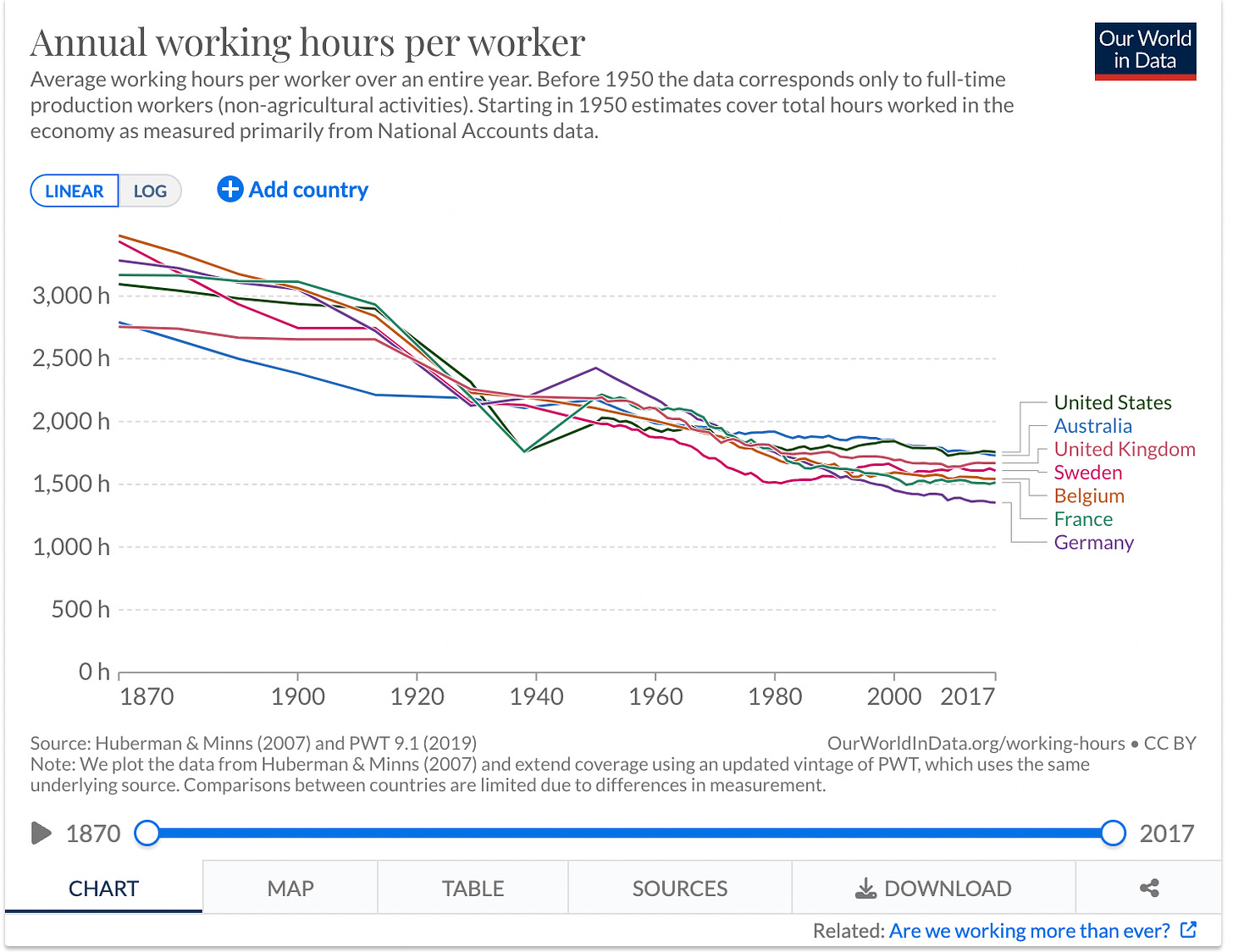

John Maynard Keynes’ Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, an essay published in 1930, is the best-known work on the subject from this period. He forecasts that, 100 years hence, “[t]hree-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week” may be widespread. Now seven years from the end of Keynes’ forecast window, it does not look like this prediction will be quite right, but there has been a long-term trend in the reduction of working hours.

To get to this point, Keynes posited that four things would be needed:

our power to control population, our determination to avoid wars and civil dissensions, our willingness to entrust to science the direction of those matters which are properly the concern of science, and the rate of accumulation as fixed by the margin between our production and our consumption; of which the last will easily look after itself, given the first three.

World population growth has slowed and is forecast to reverse in the 21st century, and the phrase “control population” is no longer considered to be politically correct. Although the most calamitous war in world history began nine years after Keynes’ essay, war deaths have been below historical norms since 1945. “[O]ur willingness to entrust to science” remains contentious. Keynes’ last point sounds like a formulation of Say’s law, and the reason for the apparent chronic economic slowdown in wealthy countries since the 1970s remains unclear. The normative aspect of Keynes’ essay are the most interesting, and we’ll come back to it later.

Recent worries about technological unemployment center on computerization, or the ability of modern machines to perform cognitive tasks as well as physical tasks, such as outlined by Wassily Leontief in 1983. Recent books by Martin Ford and by Brynjolfsson and McAfee (1,2) outline these fears. In 2013, Frey and Osborne made a widely cited forecast that 47% of jobs in the United States were vulnerable to automation. In 2023, similar work found that 47-56% of jobs were vulnerable to automation from large language models such as GPT. In 1989, Paul Samuelson made an argument for technological unemployment in a more general sense.

The most important principle to understand is that of compensation effects. These are mechanisms by which technological innovation will create employment as well as replace it. Mechanisms include labor to service the new innovations, stimulated demand for good through reduced prices, new investment, declining wages, greater real incomes, and new product creation. Those knowledgeable of energy economics will recognize compensation effects as analogous to the rebound effect, mechanisms by which some, if not all, of expected energy consumption reduction benefits from energy efficiency are instead directed to increased consumption.

Can technological unemployment be observed empirically at present? The evidence is weak. This study says no, that compensation effects continue (as of its publication in 2011) to counterbalance the productivity gains of technology. This study argues that this will remain true for the foreseeable future. This study confirms that the classic view holds: that unemployment from technology is a temporary phenomenon that is eventually corrected. However, this study finds that chronic technological unemployment is real. I would add that proponents of technological unemployment also usually overestimate the speed at new technology will diffuse, and underestimate the capital costs required, the time and skill needed to operate new technology, and social and political hurdles to technology.

Ills from labor-saving devices might manifest themselves in other ways than unemployment. Low-salary jobs requiring less education are generally the most vulnerable. Acemoglu and Restrepo find that technological innovation is, by this mechanism, a driver of economic inequality, though a recent study by Gilfoyle is more nuanced.

The most compelling, though far from convincing, explanation for the fall of working hours is that it doesn’t represent technological unemployment, but rather a voluntary and rational trade of money for leisure time that occurs as a result of the declining marginal utility of wealth that comes with more of it. Robert Gordon makes an argument to this effect, as does Dietrich Vollrath. Manfroni et al. discuss this phenomenon as a major cause of economic stagnation, a subject which I discussed a few months ago.

Modern scholarly proponents of technological unemployment are not so naive as to neglect compensation effects. Thus the lump of labor fallacy, or the Luddite fallacy, is a bit of a strawman. Nevertheless, I would assess that the balance of evidence is against them so far. Maybe this will change if great advances in artificial intelligence occur, as some enthusiasts expect in the near future.

Insofar as technological unemployment is concern, what is the appropriate response? There is the classic response of trying to ban labor-saving technology. Job automation is among the grievances cited in the recent AI Pause letter, about which I wrote critically.

Slightly more realistic is the idea of using the wealth generated from automation to finance welfare to people who lose their jobs. For example, a universal basic income was the centerpiece of Andrew Yang’s 2020 presidential campaign. To thoroughly discuss the merits of a basic income is beyond the scope of this post, though I would recommend this paper by Nguyen which highlights problems with the idea.

Believers in imminent technological unemployment are called pessimists, and skeptics (unless their belief is motivated by a lack of belief in future technological progress in general) are called optimists, reflecting the widespread view that technological unemployment would indeed be a bad thing. For example, from the Catholic Church, Popes St. Paul VI, St. John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis have all affirmed the dignity and value of work and the need to protect the rights of workers as such.

Coming back to Kenyes, though, a famous phrase from his essay is “[b]ut this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment”. He is not referring to compensation effects and the expectation that full employment will remain in the face of advancing technology, but in his predilection for long-term visions of the future, to the “economic problem” itself. Keynes believed that by some future date (2030 in this essay), humanity would transcend the need to couple meaning and survival to paid employment. Such is a prominent feature in utopian visions of a post-scarcity economy. Under these ideas, technological unemployment would in fact be an optimistic view.

But for now, I find it difficult to get excited about any policy response to technological unemployment because this is a hypothetical problem that may or may not (I lean toward ‘may not’) exist in the foreseeable future. Focus your attention instead on real problems that exist today.

Quick Hits

I recently came across this article by Adam Thierer on “Japan Inc.”. The article highlights the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), created in 1949 to govern that country’s industrial policy. Enthusiasm for Japan-style industrial policy, as well as fears that Japan was going to take over the world, reached a crescendo in the early 1990s, but since then it has become clear (in Thierer’s view) that Japanese-style industrial policy has been a failure. This is valuable historical context for evaluating contemporary enthusiasm and anxiety around the rise of China.

Christian Britschgi recent wrote about a proposal in the California legislature, AB 68, that would streamline approval for housing in “climate-safe” areas while add further process for what is derisively referred to as “sprawl”. Since most new housing is built in suburban/exurban settings, this bill would likely reduce the state’s housing production overall and raise costs. This highlights a fatal problem with the YIMBY movement. It is a coalition of urbanists, environmentalists, and low-income housing advocates. These groups are collectively responsible for most of the dysfunction that plagues California’s housing market, and thus the YIMBY movement cannot deal with the problem except in a very tangential way, lest it alienate a coalition member.

A few years it was found that social media is not associated with political polarization. Looking at various demographic groups, the authors compared measures of polarization among those groups with social media usage, and found that the two anti-correlate. This does not prove that elements of social media, such as filter bubbles, are not responsible for polarization, but it does make this idea hard to believe.

Relatedly, on the recently settled Dominion/FOX lawsuit, it was revealed during discovery that the network’s leadership and prominent hosts knowingly lied about fraud in the 2020 election. The rationale for these lies is that this is what the viewers wanted to hear. Yet most of discourse on misinformation focuses on anxiety around anonymous speech, deepfakes, and so forth. Efforts targeting supply of misinformation, and ignoring demand, will be ineffective.