Good afternoon and happy Easter.

Twitter and Substack

Yesterday, Twitter abruptly suspended the ability to interact (like, reply, retweet) with tweets containing Substack links. This is presumably in reaction to the announcement of Substack Notes, a social networking system that looks a lot like Twitter. Last December, Twitter pulled a similar stunt on competitor social networks before reversing it. I am hoping and expecting that this ill-conceived policy will be reversed soon as well. If not, then we’ll see …

Eroom’s Law

Moore’s Law, posited by the recently deceased Gordon Moore, holds that the number of transistors on a semiconductor doubles every 18-24 months. In 2012, Jack Scannell and coauthors introduced Eroom’s Law (Moore spelled backwards) to describe the apparent pattern of drug discovery becoming more expensive over time, doubling in price every nine years.

Why are costs going up? In light of major biotechnology advances of the past few decades—the Human Genome Project, cheap genome sequencing, CRISPR, AlphaFold, etc.—this trend all the more cries out for explanation.

The most obvious (to me, anyway) explanation would be that the discovery of drugs over time constitutes the picking of “low-hanging fruit”, and so the difficulty of finding new drugs becomes inherently greater. But I haven’t found much support for this in the literature, whereas quite a few articles, such as this by Scannell and Bosley and this by Rees, are dismissive of the low-hanging fruit story.

Instead, Scannell et al. posit four explanations.

The “Better than the Beatles” problem. At first glance this looks like the low-hanging fruit problem. It holds that, especially for common diseases, the success of past drugs sets a high bar for the efficacy of new drugs.

The “cautious regulator” hypothesis holds that, over time, agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have been more cautious, raising the cost per approval.

The “throw money at it” problem: over time, pharmaceutical companies have become less concerned about the efficiency of their research spending.

The “basic research–brute force” problem: over time, research has shifted to less efficient pharmacological methods.

Despite Scannell’s protestations to the contrary, it is unclear to me how the better-than-the-Beatles problem differs from the low-hanging fruit problem. Whether the FDA is overly cautious is an ongoing debate (whether the FDA has gotten more cautious over time, contributing to rising research costs, and whether they are too cautious are separate questions with possibly distinct answers).

Danzon argues that cartelization in the pharmaceutical industry explains rising costs.

Andrew Lo explains the paradoxical effect of biomedical innovation: new technological raises the complexity, and thus the cost, of research. He calls for funding models distinct from the traditional Big Pharma funding. It is interesting the observe that the shift toward academic spinoffs and startups financing drug discovery corresponds with the apparent breaking of the cost increase trend, though it is unclear to me that the two are related.

This paper argues that most of the apparent decline in efficiency is a result of research shifting to high-risk/high-reward projects.

On the subject of biotechnology advances, this paper argues that most recent advances have been most applicable to single-target drugs. But it is usually the case, as the aforementioned paper illustrates in the context of cardiovascular diseases, that diseases are the result of the interaction of many factors. This may explain why there has been a shift in research toward rare diseases, as these are more likely to have single-target explanations that are amenable to recent advances, such as AlphaFold. On that subject, Lowe explains that, while technically impressive, AlphaFold will do little to help conduct clinical trials, which are the main driver of costs, more efficiently, or to help with multi-target diseases, which are most of them.

This blog post details the inefficiency with which clinical trials are done. It is written by Lindus Health, a company that is trying to make trials more efficient.

Bloom et al. discuss drug discovery costs, and medical research more broadly, in their more general review of declining research productivity.

I’ve thrown out some explanations as to why drug discovery seems to be getting less efficient. There are several answers that seems compelling—particularly the “better than the Beatles” problems by which a high bar is set for new drugs, that regulators are overly cautious, and that the clinical trial process is dysfunctional—but no answer looks conclusive.

What can be done about this? Again, I will throw out a few ideas, though I am not sure how well any of these will work.

First, Jack Scannell proposes de-linkage, which would reduce or eliminate patent rights as the financial motivation for pharmaceutical companies to engage in research and development. In an extreme case, there would be no patent rights at all, and instead an international consortium would offer a set amount of prize money for developing a drug. This is proposed specifically for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The proposal comes at the end of a long article which is mostly about drug pricing rather than research costs specifically; there is a lot here that is interesting but tangential to this article.

Adaptive licensing is argued to help get around the cautious regulator problem. Under adaptive licensing, for diseases for which there are not otherwise effective treatments, new drugs could be approved on a limited basis on weaker clinical data. Here is one form of such a proposal.

More work on repurposing existing drugs for new conditions has been proposed. Because these drugs have already been approved for other uses, the evidentiary burden for safety would be reduced.

For all this talk of escalating research prices, Frank Lichtenberg has shown that drug discovery is still a good deal for society: he estimates the cost at $2837 for each quality-adjusted life year that the new drugs provide. In the United States, estimates of the value of a QALY typically run between $50,000 and $150,000 (layperson-friendly explanation).

Oregon Housing

Like most places around the world, the state of Oregon is suffering from escalating housing costs. A few years ago, there was legislation to force some upzoning in most urban areas. But the problem is far from solved.

On the cursed bird app, Michael Anderson of the urbanist Sightline Institute wrote this on H.B. 3414, a piece of legislation that would curtail the ability of municipalities to deny variances (in planning lingo, a variance is a grant to a developer to allow a project that would otherwise go against the zoning code). The legislation contains this clause, though, with bold mine.

SECTION 2. (1) Within an urban growth boundary, a local government may not deny an application for a variance from land use regulations for the construction of a residential development on lands zoned for residential uses, unless:

(a) The denial is necessary to address a health, safety or habitability issue;

(b) The variance request relates to the density, height or floor-to-area ratio of the development.

That seems like a major exception that would mostly defeat the purpose of the bill. Anderson says he is pushing for an amendment that would soften this language.

It would be very good to cut down on the use of variances, as this practice has been abused and is a source of corruption within cities. Knowing that they can issue variances, cities often deliberately write zoning codes that are stricter than what they intend in practice, and so when developers are forced to apply for variances, they can extract project-by-project political goodies such as community benefit agreements.

Broadly speaking, there are three solutions for high housing costs, each of which is difficult. The first solution, which is what urbanists such as the Sightline Institute have focused on, is upzoning and densification within urban areas. The second solution is extensification, aided by investment in transportation infrastructure. The third is more evenly distribute economic opportunity to economically depressed areas (see, for instance, Opportunity Zones as created in the 2017 tax bill).

All three approaches are necessary to mount an effective pro-housing agenda, but advocacy in Oregon has focused mainly on densification, ignoring, or sometimes coming at the expense of, other approaches. Oregon’s Urban Growth Boundary places strict limits on the ability of cities to expand and comes with counterproductive effects such as leapfrog development. Dealing with this is politically difficult, as shown in recent modifications to the UGB to attract semiconductor manufacturing.

Life Expectancy

There has been some disturbing news regarding life expectancy in the United States.

This chart presents data through 2021. With last year’s data, it was plausible to attribute the drop to the effects of COVID-19. This year, it is clear that there is more going on.

NPR wrote an article about the findings, citing higher childhood and adolescent mortality and higher maternal mortality. The former is based on a paper that shows that, for young people, car crashes, homicides, and poisonings have all made greater contributions to mortality growth among young people than COVID. But most of the NPR article is about a major 2013 report detailing that Americans have shorter life expectancies than citizens of most peer countries. This report might explain the persistent gap—based on the NPR article, I find the explanations to have varying levels of plausibility—but it doesn’t explain the recent drop.

Dr. Schmerling of Harvard Medical School, summarizing a CDC report, states that the two leading causes of the drop in life expectancy are COVID-19 and drug overdoses, with accidental injury coming in for a dishonorable mention. Heart disease, liver disease, and strokes are smaller explanatory factors. Deaths from some diseases were down, offsetting what would otherwise have been an even larger decline.

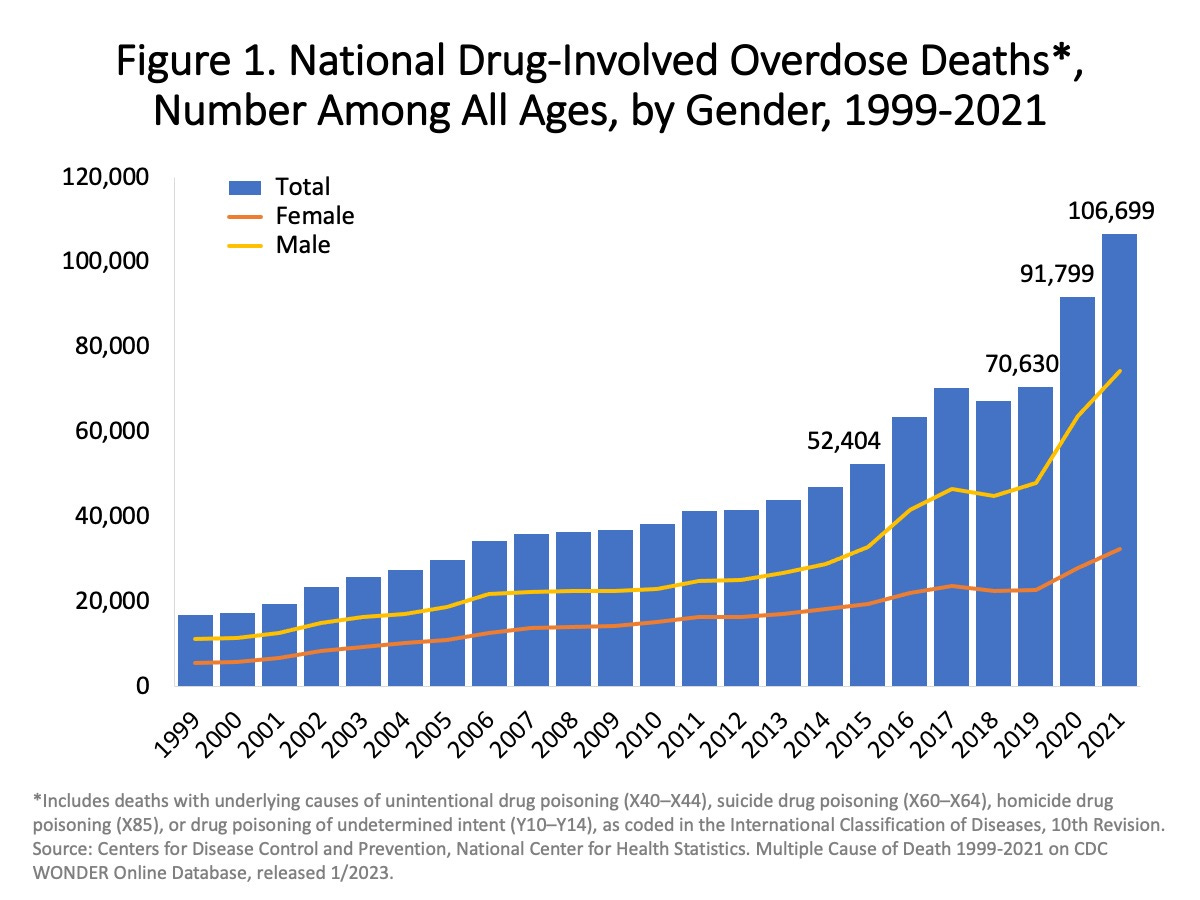

Here’s the NIH again with alarming trends in drug overdose deaths. Fentanyl is the most prominent drug driving this.

Alcoholism, which exploded in Russia around the fall of the Soviet Union, has been identified has a major cause of that country’s depressed life expectancy in the 1990s. Drug abuse is one of the most tragic manifestations of how large numbers of people can check out of meaningful participation in their societies, and drug abuse trends are a canary in the coal mine for social stability in the U.S. as well.

As of this writing, there have been over 100 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States and over 1.1 million deaths, making it almost as deadly to Americans as all wars in U.S. history combined. Several articles have asserted that the prevalence of vaccine hesitancy in the U.S. is a contributor to the high death tolls, though I haven’t found any reliable figures on that. Here’s a paper that looks at excess deaths by partisan affiliation. The breakdown in social cohesion that would motivate such destructive behavior is another warning sign whose gravity is not fully appreciated.

I won’t hazard a guess as to which way life expectancy numbers will go in the coming years. One can be optimistic that COVID-19 deaths are receding and drug overdose deaths are cyclic. One can worry that new hazards are around the corner. But in any case, American life expectancy numbers are very far from where we would want them to be.