Thoughts for October 2, 2022

Good afternoon evening for those of you on the West Coast of the United States. Today’s topics are historic economic growth, permitting reform, Italian politics, and some fun with Dall-E 2.

Historic Economic Growth

Last week I discussed the long-term economic impacts of the Black Death, and I referred to a Smithian (named for Adam Smith) conception of economic history that regards the agglomeration effect of an integrated economy as a major driver of growth. This week I would like to look further at this and related concepts.

This paper by Ortman and Lobo examines the Northern Rio Grande Pueblos in modern-day New Mexico and finds that Smithian growth applies from the period AD 1250-1650, after which point the influence of Spanish contact is no longer separable. The first half of the paper conducts a mathematical derivation of scaling properties. The authors, along with Luís Bettencourt, have done much to derive a rigorous formulation of urban scaling and agglomeration economies, and the mathematics in this paper are familiar from such past work. This is similar derivation at a superurban, societal level.

Here, the primary mechanism behind agglomeration economies is specialization; the more integrated over a large scale an economy becomes, the more opportunities there are for workers to specialize, increasing their productivity, as illustrated in Adam Smith’s parable of the pin factory. While the Pueblos became more economically integrated during this time period, they did not appreciably increase in population or technological capability. This helps separate the Smithian mechanism from other mechanisms.

The other paper I’ll highlight is Jack Gladstone’s Efflorescences and Economic Growth in World History: Rethinking the "Rise of the West" and the Industrial Revolution. It’s a good read if you want some preindustrial economic history, and I’ll share a non-exhaustive list of highlights.

Goldstone identifies three types of economic growth: extensive, Smithian, and Kuznetzian (named for Simon Kuznets) or Schumpeterian (Joseph Schumpeter) growth. Extensive growth is driven by an expansion of population and arable land, so that the size of an overall economy grows, but per-capita wealth does not grow, nor is there a change in technology. Smithian growth, as discussed above, is driven by agglomeration. Schumpeterian growth is driven by technological improvement.

The industrial age of the last two centuries is characterized by Schumpeterian growth: in excess of 2% annually, with rapid technological change. But this was not the norm prior to the Industrial Revolution.

Goldstone characterizes the traditional view this civilization, from the dawn of agriculture to the 18th century, is governed by slow, steady growth punctuated by crises, often provoked by Malthusian constraints. To counteract this view, Goldstone posits an “efflorescence”; if a crisis is a sudden period of substantial economic downturn, an efflorescence is a sudden period of economic upturn. Preindustrial progress, in Goldstone’s view, occurs mainly in these efflorescent periods. The remainder of history is a time of stagnation or crisis.

Examples of efflorescent periods include Britain from 1760-1830, on the eve of the Industrial Revolution (which Goldstone puts later than most historians); the Dutch Golden Age (1570-1670), the High Middle Ages in Northwestern Europe (which he also calls the Cathedral Age, 1150-1250), and the high Qing period in China (1680-1780). He refers in passing to other efflorescences going back to the thriving of Mesopotamian civilization after the advent of writing.

Goldstone’s four examples are from what many historians would characterize as the early modern period, but he seems not to be impressed with this term. He does not find a fundamental difference between these efflorescences and other, earlier ones in history, and stretching modernity back that far pushes the concept far past the point of usefulness.

Goldstone identifies as a pattern that an efflorescence tends to last for a few generations (he chooses to label three of them as a century), most likely to occur when a new social order takes root, evoking Mancur Olsen’s concept of distributional coalitions. If you were studying the statistics in 1830, it might appear that Britain’s efflorescence was not fundamentally different from past ones, but unlike in the past, Britain’s golden age continued on and on, accelerated, and spread around the world, changing society beyond recognition.

What made Britain’s efflorescence different? Goldstone identifies two factors. The first is energy. Previous efflorescences, especially in the Cathedral Age and the Dutch Golden Age, have been characterized by an expansion of the quantity and nature of energy available, but Goldstone argues that neither biomass or water power nor wind power could sustain the indefinite prosperity that fossil fuels did. Second, while the Scientific Revolution has begun centuries earlier, it is only with British industrialization that scientific observation came to be applied rigorously to economic production.

There is much more I want to do on this topic, and I expect that I will revisit it in the future. For now, my intuition is that the Smithian growth mechanism remains greatly underrated in modern growth, and also that it underpins modern technology to a much greater extent than is generally appreciated.

Permitting Reform

Few things are less interesting than a piece of legislation that has recently failed, but here goes. To secure Senator Manchin’s needed support for the recent Inflation Reduction Act, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer offered in exchange permitting reform. The permitting reform could not have been part of the IRA because that was done through the reconciliation process, and … well, that’s just how the Senate works. Instead reform was attempted through the spending process, which Republicans and a few Democrats opposed. I wonder if this deal could have attracted sufficient Republican support if it was a separate bill.

Ted Nordhaus wrote a piece on the values within traditional environmentalism, which differ from the ecomodernist approach, that motivated opposition to the deal. Traditional environmentalism focuses on opposition to development, even development that will reduce environmental harms, and it remains mired in concepts such as “Limits to Growth”, or its updated analogue, “planetary boundaries”. This piece follows up on another, The Death of Environmentalism, by Ted and Michael Shellenberger, which was an important influence on my own thinking on the subject.

In a recent newsletter, James Pethokoukis referred to a proposal that President Carter made in 1979 for an Energy Mobilization Board, which would have been modeled after the War Mobilization Board to accelerate procurement during World War II. Carter discussed this as part of his notorious “malaise speech” on energy; here is the relevant passage. The political scientist Sidney Plotkin discussed the legislative failure of the EMB a few years later and echoed many of the same themes discussed in the pieces linked above. Carter had difficulty convincing environmentalists that the EMB’s fast tracking could be done without compromising environmental quality, and after initial support, Republicans turned away from the EMB in favor of the more deregulatory approach espoused that their presidential candidate, Ronald Reagan. The fact that we are having the same discussion more than 40 years later does not make me optimistic that a solution is at hand. More recently, the Trump administration attempted to streamline NEPA timelines through the regulatory process, but that was mostly undone after Biden took office.

Why do most environmental organizations oppose permitting reform? I’ll give four answers, in ascending order of cynicism.

At least since Silent Spring in 1962, a “David versus Goliath” tone has been set, where environmentalists like to imagine themselves as the public interest-minded David fighting against the moneyed Goliath of corporate interests. Most environmentalists believe this sincerely; I once believed it too. The permitting process is the most important arena on which these fights take place.

There is a division of labor in policy advocacy, where most environmentalists see their job as protecting the environment, and industrial development is someone else’s job. They simply don’t see energy security, economic prosperity, or job creation as their concern.

As discussed in the aforementioned piece and quoted in a Rolling Stone article,

“Look, I want to get carbon out of the atmosphere,” [environmental activist Jamie] Henn continues, “but this is such an opportunity to remake our society. But if we just perpetuate the same harms in a clean-energy economy, and it’s just a world of Exxons and Elon Musks — oh, man, what a nightmare.”

The article leaves the details of “remake our society” to the imagination, but I have to assume that it refers to some form of ecosocialism. Advocates of this ideology don’t want to see environmental challenges be addressed in the context of a capitalist, growth-oriented system, and so they oppose addressing challenges. Instead they use the economic dislocation caused by regulatory sclerosis as a vehicle for pushing through broader changes, an analogue of the immiseration thesis.

The Shirky Principle applies: entrenched environmentalism, like most entrenched lobbies, is more concerned with protecting their own position than they are with protecting the environment. Opposing projects through the permitting process is an excellent fundraising tool that they don’t want to give up.

Italian Politics

There were elections in Italy a few days ago, where Giorgia Meloni, characterized as the most far-right prime minister-to-be since Mussolini, came out on top. Although her party, Brothers of Italy, has roots in the fascist movement of the 1920s-40s, Meloni rejects that label for reasons that should be obvious.

I have never lived in Italy, and my qualifications for commenting on Italian politics are that I visited Rome for a week about five years ago. But since that’s a week longer than most pundits who have weighed in, here we go. In trying to understand what is going on, the first place I would look is here.

Western Europe as a whole is performing poorly economically, and Italy is one of the worst performing countries in Europe. One shouldn’t be surprised that this poor performance would fuel public resentment against immigrants and the European Union, planks on which Meloni’s party ran, especially given the EU’s chronic inability to turn around the economic situation across the eurozone.

The term “right-wing populist” has been coined for a worldwide phenomenon of political movements that have, as general characteristics, opposition to transnational movements, dislike of immigrants, nationalism, and populism (opposition to “The Establishment”, whatever that is). Purported members of this movement include Viktor Orbán of Hungary, Jair Bolsanaro of Brazil, Nigel Farage of the United Kingdom, Donald Trump of the United States, Andrzej Duda of Poland, Marine Le Pen of France, Meloni of Italy, and many others.

Before any of these people took power, there was Silvio Berlusconi of Italy, the on-again-off-again prime minister since 1994. Since then, Italy has also seen the Five Star Movement and Matteo Salvini. The astute observer will notice that nearly 30 years of mostly populist right government have shown no evidence of improving the economic situation.

Describing this as a worldwide movement elides important differences. For example, Orbán, despite Hungary being a NATO and EU member, has quasi-supported the Russian invasion of Ukraine, while Poland under Duda has been one of the staunchest supporters of the Western Alliance.

Describing the aforementioned movement as “fascist” gives them too much credit. Slogans from Meloni such as “God, fatherland, and family” make me roll my eyes, since what I see for the most part is a lot of grandstanding and airy ideology that has little relevance to problems that people are actually facing. It may seem that I complain a lot, but what I ask for is quite simple. Give me tangible, workable solutions to actual problems. Otherwise, this movement will go down in exactly the same way as those they criticize.

Fun with Dall-E 2

Dall-E 2, the image generator neural network, is now available for the general public. I had some fun with it this week. Here are a couple of the images I made from it.

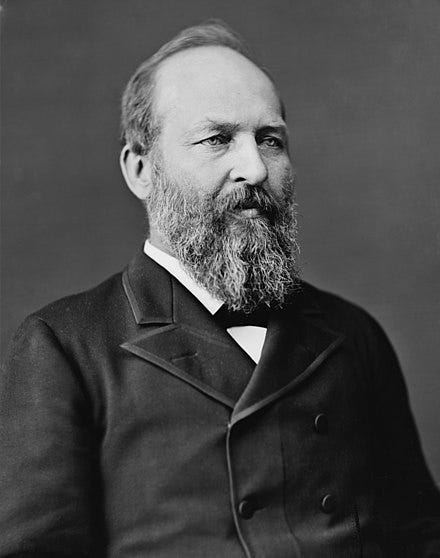

How does the system handle potentially ambiguous words? For example, “Garfield” might refer to the Garfield comic strips about a fat, orange, lasagna-eating cat by Jim Davis, or it might refer to James Garfield, the 20th President of the United States.

Not bad. The face is off though, and something is wrong right the right hand. And what’s going on with the microphone? The guy maybe, sorta looks like James Garfield … if you squint hard enough.

The other thing that’s weird is that black border. The shape looks a little bit like a cat head. Garfield the cat? Whoa, mind blown.

Each prompt generates four images. Here’s another one.

The coloration looks a little bit like a late 19th century photograph, which would be appropriate given the subject matter. That’s pretty neat. But that’s the Capitol Building behind him, not the White House.

I tried a historical event, the negotiation of the Oslo Accord. Dall-E 2 choked on this one.

I don’t know if Dall-E 2 uses any commercial or copyrighted material in its training set, but based on the following, I’m guessing not.

I could go on, but this is getting long and it’s getting late. Overall, while this was fun and a very impressive illustration of the power of deep learning, it feels like we’re a long way from anything useful. The failures of Dall-E 2 to perform as hope were many, and some of the successes could have been pareidolia as much as real successes. Most of my prompts have been adversarial, in that I am trying to find ways to make the system choke. Maybe if I tried to work with it and got some practice, I could make it perform as desired.