The Legacy of Jimmy Carter

As you have probably seen in the news, Jimmy Carter died last Sunday at the age of 100. Carter was the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 and the last surviving president from the Cold War era. Much has been written about him this week, but seeing as Carter is one of my favorites, I will attempt to add to that. In this short space and with limited time, I cannot attempt a comprehensive overview of the Carter presidency. For that, I would recommend Burton Kaufman’s and Scott Kaufman’s The Presidency of James Earl Carter, Jr., as part of the University Press of Kansas’ American Presidency series. Nevertheless, I am glad to see that in recent years, the importance and value of the Carter administration’s accomplishments is coming to be more greatly appreciated, and this focus is not just on the shortcomings, which are real. Today, we’ll look at both.

Human Rights in Foreign Policy

An outsider to Washington politics and a devout Christian, one of Jimmy Carter’s goals upon assuming the White House was to make human rights a central focus of American foreign policy. He understood it to be the morally right thing to do, and he also understood the importance of human rights as a source of Western strength in the Cold War. Furthermore, a newly assertive Congress after Watergate and NGOs such as Amnesty International had helped bring human rights, especially in Latin America, to the forefront of public attention. Daniel Fried, who served in the State Department at the time, recounts the policy. In his Inaugural Address, Carter stated,

Because we are free, we can never be indifferent to the fate of freedom elsewhere. Our moral sense dictates a clear-cut preference for those societies which share with us an abiding respect for individual human rights.

A human rights focus would entail consideration of human rights in foreign aid and trade deals, and it meant public statements against human rights abuses in other countries. Several administration initiatives culminated in Presidential Directive 30, issued on February 17, 1978, which stated,

In promoting human rights, the United States shall use the full range of its diplomatic tools, including direct diplomatic contacts, public statements, symbolic acts, consultations with allies, cooperation with nongovernmental organizations, and work with international organizations.

During the Cold War, it was too often the case that the United States would overlook atrocities in other countries, so long as they were anticommunist. Bradley (2021) discusses the limitations of the human rights focus in Argentina. In 1976, a right wing military junta took power and committed severe atrocities in its effort to root out leftist guerrillas in what came to be known as the Dirty War. Breaking with the tradition of unqualified American support for anticommunist governments during the Cold War, regardless of their human rights record, Carter publicly condemned the Argentinian junta and withheld military aid.

Much of the bureaucracy at the State Department resisted the human rights focus, and the internationalization of the Dirty War into Bolivia and other countries raised the perceived geopolitical stakes of the human rights policy, which seemed to be of low cost when the junta’s focus was domestic. Carter was furthermore distracted by other foreign policy issues, especially the Iran hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, during the second half of his term, and the administration’s human rights pressure on Argentina eased. When Ronald Reagan reverted toward a traditional policy in Latin America, it was no longer a great shift.

Behind the Iron Curtain, the Carter administration’s human rights advocacy in Poland found limited success, as illustrates Tyszkiewicz (2022). It had been U.S. policy since Dwight Eisenhower to cultivate good relations with Poland and cultivate liberalism there, as Poland was seen as a weak link in the Soviet bloc. Carter’s national security advisor, the Polish-American Zbigniew Brzezinski, urged Carter to use human rights as an ideological tool against the Soviet Union. During the Carter years, Karol Józef Wojtyła was elected as Pope John Paul II, and the trade union Solidarity was founded under Lech Walesa. Both would go on to play major roles in the collapse of communism in Poland and eventually the entire Eastern bloc.

However, Tyszkiewicz notes that the Carter administration had to walk a fine line, not promoting Solidarity too strongly, for fear of provoking Soviet repression as happened in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Carter’s record on human rights promotion is a mixed bag at best. The goal was motivated by deep-seated Christian faith and revulsion at what he perceived as the cynical realpolitik of the Nixon/Ford administrations. But stung by harsh geopolitical realities, Carter moved away from human rights rhetoric in the second half of his term. In the 1980 election, Ronald Reagan argued that Carter’s idealistic thinking was responsible for the advance of left-wing movements in Latin America, the rise of an anti-American theocracy in Iran, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and other geopolitical crises. It is not clear to me if Carter’s were right instincts that failed to play out as hoped, or if critics were right that human rights advocacy is ultimately naiveté. I find the latter possibility distressing, if it means that we must accept evil in the world for the sake of geopolitical advantage. The matter is no more settled today than in the 1970s or, for that matter, in the time of Klemens von Metternich.

Reagan, it turns out, despite his sharp criticism of Carter’s foreign policy in the 1980 campaign, would not shy from his own idealistic rhetoric and policies. He famously described the Soviet Union as an evil empire, and he expanded on Carter’s support of the mujahideen rebels in Afghanistan. Many leading neoconservatives built their careers under Reagan and would shape the foreign policy of the George W. Bush administration after September 11, with democracy promotion in Iraq as their central project. The perceived excesses of the War on Terror has led to a renewed cynicism about the propriety of human rights in foreign policy. My prediction that the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 would lead to a renewed interest in military strength and moral clarity has, at least so far, not appeared to have materialized.

Other Foreign Affairs

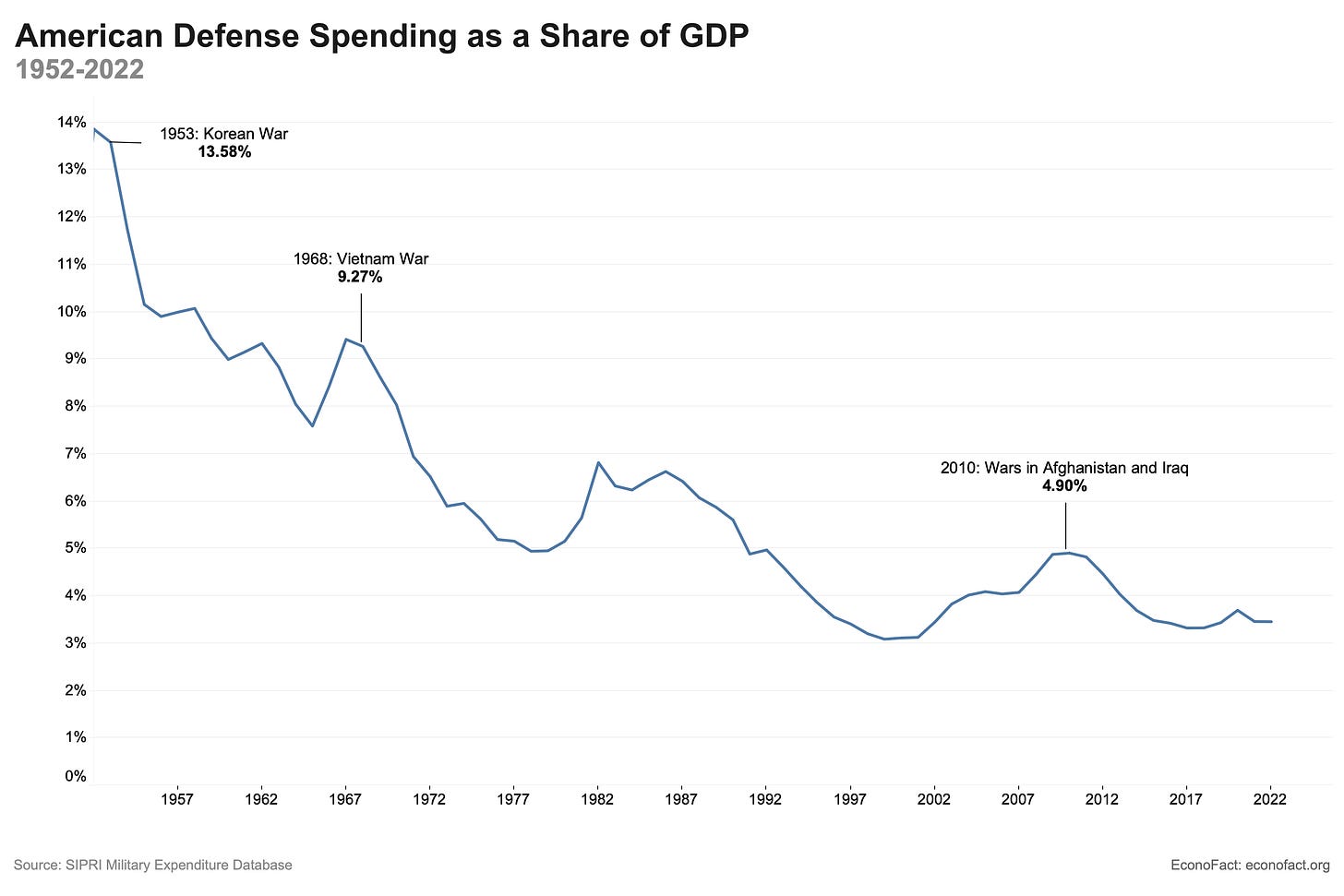

American defense spending, as a share of GDP, reached post-World War II lows under Carter.

In 1979, the Defense Department and the RAND Corporation produced the docu-drama “First Strike”, simulating a successful Soviet nuclear attack against the United States that is allowed to occur because the U.S. had underinvested in key weapons systems. The video’s main purpose was a sales pitch for more defense spending, which as you can see from the above chart, Reagan delivered on. Whatever the foreign policy goal, it is hard to succeed without the resources to back it up.

Carter’s greatest success was the Camp David Accords. From September 5-17, 1978, Carter brought Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin to Camp David and began building a framework that would lead to a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel in March 1979. The treaty was a long shot; Begin represented the hardline Likud party, which opposed any peace treaty which would relinquish land claims. For this treaty, Sadat was assassinated by Islamist extremists in 1981.

Deregulation

Ronald Reagan’s economic policies are strongly associated with a deregulatory, free-market agenda, but many important deregulatory policies were instituted under Jimmy Carter.

In 1978, Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act, the first major deregulatory policy since the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated the National Recovery Act in 1935. The bill eliminated the authority of the Civil Aeronautics Board to set airfare, and it greatly freed the ability for new airlines to begin operation, which led to the advent of low-cost carriers, among other provisions. Alfred Kahn, writing in the early 1990s, finds that the act lowered airfare by 10-18% relative to what it would have been without deregulation. Additionally, the act led to more efficient operations and improved safety.

In 1980, Carter signed the Motor Carrier Act, which deregulated the trucking industry. Similar to the Airline Regulation Act, the Motor Carrier Act phased out price controls and greatly reduced the barriers to entry for new trucking. The bill additionally relaxed restrictions on what commodities truckers could carry and the geography in which they could operate. That same year, Carter signed the Staggers Rail Act. Jerry Ellig finds that these two bills both greatly reduced the cost of trucking and rail transport. Because of the enhanced freedom of competition, the number of trucking jobs increased from one to two million. Especially telling is that since the Carter administration, there have been no serious proposals to reverse the deregulation.

In some ways, Carter turned away from the New Deal style of policy that had dominated Democratic politics since Franklin Roosevelt and advocated welfare and tax reform. In 1977, Carter submitted a welfare reform proposal which, among other provisions, would have instituted work requirements for most recipients of federal aid who can work. The proposal never passed, but elements of the proposal were incorporated into the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act. Carter also proposed to lower taxes, particularly on lower brackets, but that too did not pass.

Overall, many of Carter’s economic policies look more like what Ronald Reagan did than what John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, Carter’s Democratic predecessors, would have done. Carter’s turn from Democratic orthodoxy provoked a serious primary challenge from Ted Kennedy, which Stanley (2009) argues failed more for the weaknesses of the Kennedy campaign rather than a philosophical shift in the party at large.

Much of the attempted realignment under Carter would be attempted again, this time more successfully, under Bill Clinton. Center-left leaders around the world in the 1990s and 2000, including Clinton, Tony Blair, and Gerhard Schroder, comprised the Third Way position. The ideology exists today in the Center for New Liberalism.

Legacy

As Kaufman and Kaufman recount, one of Carter’s greatest weaknesses as a leader was an inability to prioritize. He would send long lists of proposals to Democratic leaders in Congress, and when asked which were the highest priories, he would say, “all of them”. He vetoed what he characterized as wasteful pork barrel spending, was unable to get key priorities through Congress, and refused to take part in the wheeling and dealing that his predecessors were more comfortable with. In 1976, Carter’s honesty and morality were welcome in the wake of Watergate, but by 1980, his image had morphed into scolding and moralistic.

Nothing sums it up better than A Crisis of Confidence, or the “malaise speech” (despite that word never occurring in the speech) of July 15, 1979. There are many commendable proposals in the speech, such as a permitting reform proposal which, unfortunately, has yet to become a reality 46 years later. However, the speech is not delivered very well, and it comes across as blaming the public for the various problems that were besetting the country.

Ronald Reagan won the 1980 election in a landslide. One wonders, if Carter had been more politically savvy, what more his administration could have been.

Carter’s post-presidency lasted for nearly 44 years, shattering the previous record of 32 years set by Herbert Hoover. During that time, Carter gained deep respect, including from many of his political opponents, for his work building houses with Habitat for Humanity and democracy and peace promotion through the Carter Center—work for which we won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002—making his the most active post-presidency up to that time. However, Carter did not shy from criticizing his successors, including Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump.

Jimmy Carter might not have been the greatest president—though I think he was better than the negative historical record would suggest—but he was a great role model. He exemplified honesty and integrity, hard work, and a commitment to doing good that lasted for as long in his long post-presidency as his health would permit.

Quick Hits

Happy New Year. Last week I pointed out that 2025 is a perfect square, but also the square root, 45, can be expressed as 20+25. So 2025 = (20+25)². Pretty neat.

Vaporwave is one of my favorite niche musical genres. When any cohort reaches a sufficient age, it develops a certain nostalgia genre of art that is a highly idealized, or a highly distorted, image of the time period it is meant to represent. Vaporwave is a style of music based loosely on elevator, R&B, and lounge music from the 1980s and 1990s. Recently the YouTuber Aluminum Oxide released the 2:20:50 T W I N T O W E R S I I I, with imagery of our favorite buildings from that time. As the name implies, there is a Part 2 and a Part 1. FallingAsleep to the Weather Channel is another mix, dedicated to all those people who thought they were the only ones who liked classic Weather Channel. There is Welcome to the Lobby!, a tribute to all those shopping malls that have closed. The most famous might be News At 11, an 1:11:09 mix that features vaporwave tracks interspersed with television clips from the morning of September 11, 2001, before the breaking news of the day had started. I used to roll my eyes at the older generations whose aesthetic tastes seemed to be stuck hopelessly in the past, but now I am becoming that.

https://pjmedia.com/matt-margolis/2024/12/31/the-left-goes-full-orwell-to-rewrite-jimmy-carters-legacy-n4935558