In Defense of Operation Cyclone

Thanks for bearing with me the last few weeks. I have had some medical issues which prevented me from writing last week, and kept me to a late and short post the week before. Those issues are now hopefully resolved. Two weeks ago, I had intended to write about Operation Cyclone, which was the American program to support mujahideen rebels in Afghanistan against the Soviet invasion of that country in the 1980s. And so here it is now.

I wrote about this issue briefly a few months ago in the context of the ideological origins of the September 11 attacks, and since then I have wanted to revisit the subject in greater detail. The role of the mujahideen and Afghan Arabs plays prominently in most narratives on the subject, such as in Lawrence Wright’s The Looming Tower: Al Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. And yet, there is much about Operation Cyclone that is misunderstood. Today, I want to look at how the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the resistance to it came about, how the war proceeded, and what role it may have had in stoking violent jihadism.

Why did the Soviets Invade Afghanistan?

The first set of misunderstandings about Operation Cyclone revolve around the reasons for it in the first place, and so we’ll start with how the invasion came about.

By the 1970s, the revolutionary fervor that had animated the Soviet Union during the Vladimir Lenin era was long gone, but Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev felt compelled to defend communism in those countries that the Soviet Union regarded as of vital interest. To that end, the Brezhnev Doctrine was declared in 1968 to retroactively justify the invasion of Czechoslovakia that year. The doctrine declared that a threat to communism in any Warsaw Pact country was a threat to all of them, calling for a Soviet response.

Afghanistan was not in the Warsaw Pact, but the Soviets had in them a lukewarm leader in Mohammad Daoud Khan, the long-term prime minister who took power in a coup in 1973. In his five year reign, Khan drifted toward a stance of non-alignment and sought to sideline communist elements in Afghan society. Khan also took an irredentist Pashtunization policy toward Pakistan, then an American ally, rejecting the Durand Line which had long been the internationally recognized border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Khan himself was deposed and killed the 1978 Saur Revolution, which brought the openly communist Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, established by the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The party was split into two factions, Khalq and Parcham, neither of which had much popular support. The government came to be dominated by Hafizullah Amin, a ruthless leader who sought to emulate Lenin’s Red Terror.

Communist revolutionary fervor and Amin’s reign of terror did not sit well in Afghanistan’s religiously conservative society, and a coalition known as the mujahideen (strugglers or strivers, doers of jihād) emerged to, in their view, defend Islam and traditional Afghan culture from communism.

Alarmed with Amin’s incompetent rule and the widening insurgency, the Soviet Union invaded on December 24, 1979, to install a leader from the Parcham faction, Babrak Karmal, and to put down the insurgency.

Was the Soviet Invasion Provoked?

Now we come to the first major controversy about Operation Cyclone, which is whether it was the policy of the United States in 1979 to provoke a Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and thereby deplete their resources. There are two dimensions to the question: whether it was the goal of the United States to provoke an invasion, and whether American policy actually did so. I am skeptical on both fronts.

Operation Cyclone is very much associated with Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy, but it began under Jimmy Carter, specifically on July 3, 1979, nearly six months before the Soviet invasion, when Carter signed a secret directive for the first round of aid to the rebels at an amount up to $695,000 of non-lethal equipment. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski had supposedly hoped that American assistance to the rebels would induce the Soviets to respond militarily, dragging them into a quagmire not unlike the American involvement in Vietnam a decade earlier.

White (2012) also highlights March 1979 comments by Defense Undersecretary Walter Slocombe, who pondered the value of “sucking the Soviets into a Vietnamese quagmire”.

Against this view, Tobin (2020), citing documents that had since been declassified, finds that the Carter administration had neither the desire nor the expectation to induce a Soviet invasion. Rather, the first round of aid was provided in 1979 in response to growing Soviet influence in Afghanistan and in preparation for a possible invasion. Haslam (2022) argues against Tobin’s thesis and that the Carter administration has indeed set up an “Afghan trap”, though he doesn’t offer much more than circumstantial evidence to support this view.

Riedel (2014) concludes that the U.S. intelligence community did not expect a Soviet invasion in 1979, and that a main purpose of the aid was to improve relations with Pakistan, which has been soured over nuclear proliferation and a U.S. attempt to improve relations with India.

Also relying on documents that were later declassified, Gibbs (2006) assesses that the primary Soviet motivation for the invasion was the fear—probably correct—that the establishment of an Islamic theocracy in Afghanistan would destabilize bordering Soviet regions in Central Asia with high Muslim populations. Sallee (2018) finds little evidence to support the view that the invasion of Afghanistan was part of a plan to build Soviet influence in the Middle East or to counter Western influence.

In short, the evidence that there was an “Afghan trap”, or a deliberate effort to provoke a Soviet invasion, is circumstantial at best and does a poor job to explain the Carter administration’s motivations or Soviet motivations.

The Conflict

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan lasted from 1979 to 1989. As indeed might have been predicted, the Soviets expected the operation to last for no more than a year. An estimated 620,000 Soviet troops participated in the invasion, with as many as 120,000 participating at a given moment. The Soviets suffered 14,000 to 26,000 troops killed, compared to 58,000 Americans killed in Vietnam. Recognizing the war as a quagmire, Mikhail Gorbachev planned to withdraw as early as 1987 and took nearly two years to do so. Getting in was indeed much easier than getting out.

Operation Cyclone lasted from 1979 to 1992, outlasting the Soviet invasion and even the Soviet Union itself. After the Soviet withdrawal, the USSR continued to support the communist Afghan government. With that support gone in 1992, the PDPA was no longer a viable entity and collapsed that year.

Key proponents of the operation in the United States were Congressman Charlie Wilson (D-TX), Michael Vickers of the CIA, and CIA regional head Gust Avrakotos. The story is told in George Criles’ 2003 book Charlie Wilson’s War and the 2007 film adaptation, which have come in for considerable criticism for their historical accuracy. It was the largest CIA program to support an insurgency. Support from all nations—principally the United States and Saudi Arabia—to the mujahideen cost $6-12 billion, which contrasted to $36-48 billion spent by the Soviet Union. American support consisted of the distribution of weapons and other supplies, which primarily went through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence.

In 1986, the Reagan administration rather belatedly decided to supply stinger surface-to-air missiles to the mujahideen, which gave them the capacity to shoot down Soviet Mi-24D helicopter gunships. The Stinger was not the first SAM to be used in the conflict, but it was by far the most effective. The Mi-24D was the workhorse of the Soviet invasion, and while initially devastating, pilots learned to defend against Stingers. Walter Kunkle at Small Wars Journal assesses that it was faltering Soviet will and ability to prosecute the war, rather than the Stinger, that was decisive in a mujahideen victory.

The war in Afghanistan became a cause celebre throughout the Arab world, attracting around 10,000 volunteers, known as “Afghan Arabs”, to fight against the Soviets over the course of the war. This contrasts to 200,000-250,000 Afghan mujahideen fighters, and so we should be careful not to exaggerate the importance of foreign fighters. Among the Afghan Arabs were Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the principle architect of 9/11; Ayman al-Zawahiri; and Osama bin Laden.

Contrary to myth, there is no evidence that the CIA had contact with bin Laden or provided him with any support. One could argue that a war effort is fungible and that it doesn’t matter very much, or that documented CIA support for Jalaluddin Haqqani, founder of the Haqqani terrorist network, or for Gulbuddin Hekmatyar doesn’t look much better.

An estimated one to three million civilians were killed, and as many as five million were displaced as refugees, creating a severe crisis in neighboring Pakistan. The country’s infrastructure was mostly destroyed during the invasion, and ongoing conflict has prevented new construction and maintenance. Human Rights Watch claims “both sides” engaged in human rights abuses, but those committed by the Soviet invaders and their client in Kabul were far worse.

A Question of Blowback

Blowback is CIA lingo for undesired consequences arising from a covert operation. It is also the title of a book by Chalmers Johnson, arguing that blowback is the norm for American foreign policy.

As some Afghan Arabs who joined the mujahideen in Afghanistan went on to careers in al Qaeda and the Taliban, critics of American support for the mujahideen assert blowback as part of this effort. Such claims should be considered critically.

Derryl Li of the Middle East Research and Information Project discusses several problems with this argument. First, it is simply not accurate to conflate the mujahideen, the Taliban, and al Qaeda. The Taliban began as an insurgency in 1994, well after the PDPA was out of power, while al Qaeda was formed in 1988.

Second, the article questions the narrative of radicalization. It is generally assumed that conflict zones attract idealistic adventurers who become radicalized by their experience and also equipped with military skills, a combination that they might then turn against erstwhile sponsors. An alternative narrative is that these fighters were already radicalized, hence their going into a conflict zone to fight in the first place. I am not aware, for instance, of a similar phenomenon among international volunteers in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939.

This is not to suggest that the CIA was blameless for the problems that occurred in the 1990s and up through 2001. The 9/11 Commission Report documents extensive intelligence failures in the years leading up to the attacks, most infamously the poor communication between the CIA and the FBI that caused them to fail to recognize clear dangers. It is for this reason that many intelligence agencies were placed under the new Department of Homeland Security in 2003, though neither the CIA nor the FBI were moved there.

Another failure, discussed by Kotarski (2018), was that the CIA relied too heavily on Pakistan’s ISI, which preferred to fund more radical fighters rather than the moderates that the CIA would have funded. The CIA should have asserted more control over the funding process.

But the biggest failure would have to be that, after the PDPA was defeated, the CIA declared victory and went home. In 1992, Afghanistan was only concluding the first of three phases of civil war that raged from 1989 to 2001. Following the fall of the PDPA, mujahideen groups established the Islamic State of Afghanistan (not to be confused with the contemporary Islamic State), an ineffective government that was characterized by the second civil war. The Taliban emerged victorious from that in 1996, from whence the ISA became the Northern Alliance, a government in exile.

Ahmad Shah Massoud, who the CIA should have backed, was one of the leading mujahideen commanders. Unlike Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Massoud supported the Peshawar power sharing agreement that established the ISA. Massoud created the Northern Alliance in 1996 after the Taliban seized control in Kabul. In 2001, Massoud spoke at the European Parliament about the threat that the Taliban and al Qaeda posed. Massoud was assassinated by al Qaeda agents posing as journalists on September 9, 2001, two days before Massoud’s warning came to pass.

Aftermath

As discussed above, there is little evidence to suppose that the Soviet Union was goaded by Operation Cyclone into invading Afghanistan, nor that this was the Carter administration’s intention. If it was, though, then it would have been a major success. According to Kramer (1989-1990), writing just as the Soviet invasion was ending, the bad experience in Afghanistan contributed to Gorbachev’s decision not to intervene when communism was threatened in Poland and East Germany, thus playing a major role in the collapse of the communist bloc and soon after of the Soviet Union itself.

Afghanistan, tragically, has been mired in continuous warfare since 1978, including the PDPA coup, the Soviet invasion, the three-phase civil war from 1989 to 2001, the American invasion in 2001 and long Taliban insurgency, the Taliban reconquest in 2021, the ongoing Republican insurgency, and the Taliban-ISIS-K conflict.

The United States abandoned Afghanistan once before in the 1990s and was forced by foreseeable events to return. As I’ve said many times before, the United States abandoned Afghanistan a second time in 2021 and will once again be forced by foreseeable events to return at some point in the future.

Quick Hits

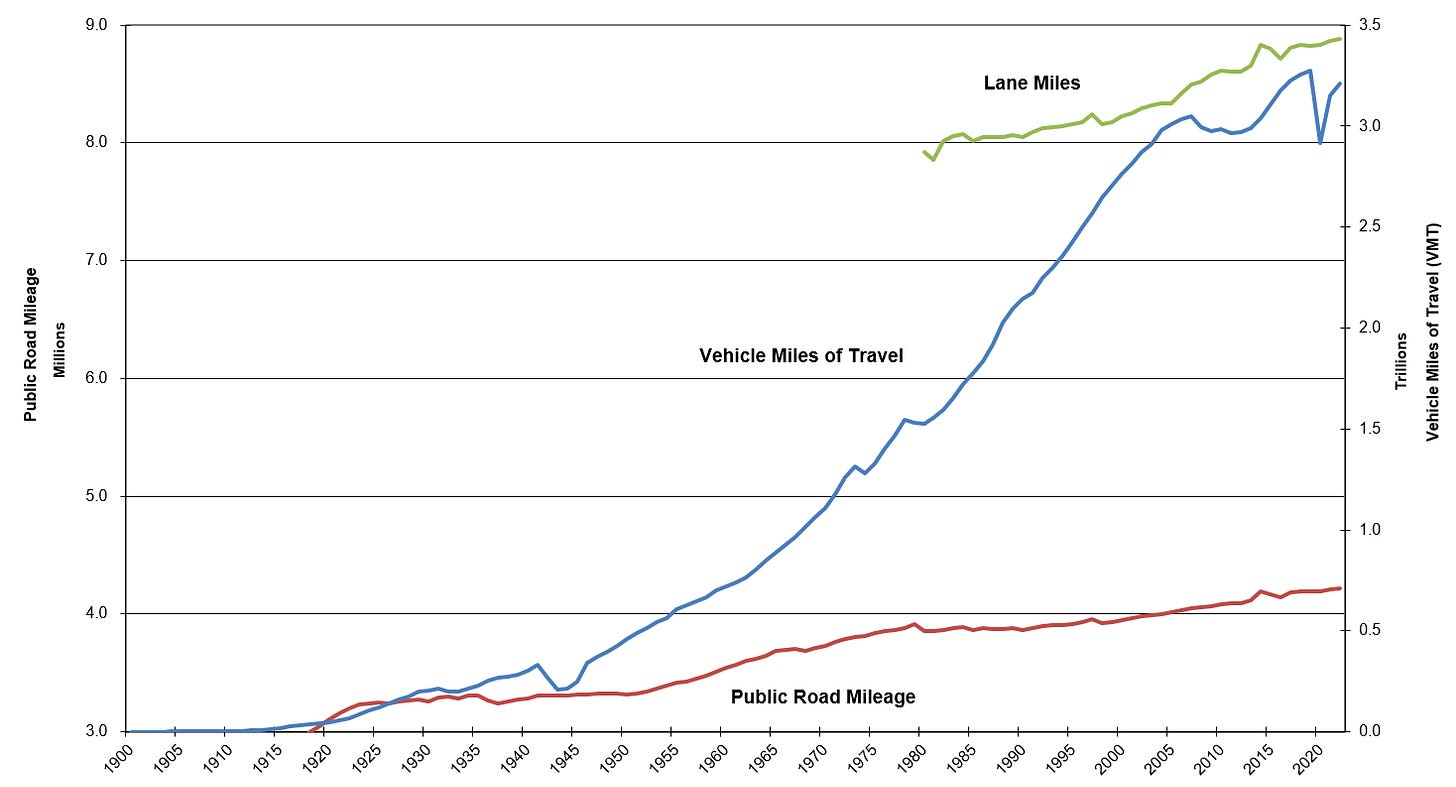

On my Scaling in Human Societies project, I wrote a more extended version of a post I did here a few weeks ago on the rebound effect in transportation. In that post, I included an image showing how vehicle-miles traveled is greatly outpacing road capacity. Here is a more recent version of that figure from the Federal Highway Administration.

You would never guess it from the Democrats’ rhetoric in the recent presidential election, but the Republican Party and their standard-bearer adopted a functionally pro-choice position on abortion in 2024, as discussed by Ed Mechmann, Director of Public Policy and the Director of Safe Environment at the Archdiocese of New York. The pro-life movement has clearly been in serious trouble for a long time, well before the 2022 Dobbs decision from the U.S. Supreme Court.

Nick Nielsen has written several posts recently about what he calls non-integrated industrial production. A characteristic of the industrial economy, especially since the 20th century, has been integrated production, meaning that almost all industrial products are highly dependent on world-spanning supply chains. In my mind, it is an open question whether this is an essential feature of industrialization, or whether it is desirable but not essential, or whether it is dispensable. If the world economy does face a collapse in coming years, such as defined by Joseph Tainter as a major reduction in complexity, perhaps due to demographic decline, we may find out.

For the Jamestown Foundation, Thomas Kent has a new, freely available book How Russia Loses. The book is chock-full of historical background on six case studies: Ukraine, South Africa, the Sputnik COVID-19 vaccine, Nord Stream 2, relations with (North) Macedonia, and relations with Ecuador.

Another great article.

One additional point that I did not see is that Al Queada was not a combat organization in the Afghan insurgency against the Soviet Union. Al Queada means “The Base.” It was meant to be a base of operation, not a combat organization.

It was about providing monetary and logistical support.

Al Queada was only involved in one skirmish with the Soviets and that was at the very end of the war. Apparently, Bin Laden showed real bravery, and that is what created his reputation as being a fighter. But it was the exception, not the rule.

It was only after the Soviets left that the organization shifted to combat and terrorism.