This week, I am continuing on the theme of sustainability, and a good way to close out the year is with a blast from the past. Today we’ll look at the peak oil idea: what it is, where it came from, and whatever happened to it.

The Hubbert Peak

The three major fossil fuels—coal, petroleum (crude oil), and natural gas—are critical to the functioning of the modern economy, and today they still comprise more than 80% of the world’s primary energy supply. As the name implies, fossil fuels originate in the decomposition of plant, animal, and microbial life over hundreds of millions of years, and thus they are not renewable over time scales that are relevant to human civilization. It stands to reason that there must be an effectively fixed ultimate potential of recoverable fossil fuels, which implies that in the plot of annual production, there must be an all time peak.

I have not been able to trace the origin of concerns about fossil fuel depletion, which I imagine must go back to the earliest extraction of fossil fuels (if anyone knows some early references, I would appreciate it), but the earliest serious analysis that I am aware of is the Hubbert (1956). M. King Hubbert was a petroleum geologist at Shell who made several important contributions to geology, and he is most famous for what is now known as the Hubbert peak, introduced in the 1956 paper.

Hubbert found that, when one plots the annual production of an oil field or of a region, it tends to form in an idealized sense a normal curve, or a bell-shaped curve. Normal distributions are common among observed phenomena, and so to find a normal distribution in annual oil production of a region is not surprising. A normal curve may initially look exponential, where the value increases by a certain fixed percentage every year, but eventually the observed growth rate decreases, a peak is reached, and then there is a decline, which is the mirror image of the increase.

If the eventual production profile of a region is taken to follow a normal curve, then one can apply a best normal fit to the production of the region observed so far to estimate the ultimate recoverable reserve of that region. Hubbert applied exactly this technique to oil production in the United States and—recall that this was published in 1956—forecast that production in the lower 48 states would peak either in 1965 or in 1970. An actual peak occurred in 1970, making Hubbert’s forecast one of the better predictions of resource depletion that has been done. At least for a while.

I am focusing on oil here. Hubbert forecast that the U.S. would reach a peak in gas production about five years later than for oil production, while coal, the first fossil fuel to be used commercially on a large scale, was also the most abundant and farthest from a peak. Hubbert made a more speculative attempt to forecast a world peak oil production and placed it “about half a century” after the American peak, which should be 2015-2020, though he also said it would be around 2000. According to the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy, world peak oil is no earlier than 2023.

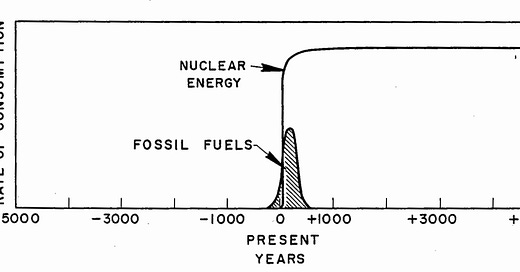

Before we consider how Hubbert’s forecast has held up over the long term, one of the more interesting and less appreciated aspects of the paper is its advocacy for nuclear power, despite that being right in the title. Hubbert forecast that if world population could be stabilized—anxiety about population growth was widespread in those days—then nuclear power, then a nascent industry, could provide the world with a high standard of living for at least 5000 years. Some authors, such as Dittmar (2013), are much less sanguine about uranium availability.

Has the Hubbert Peak Held Up?

In the same year that Hubbert published his work, President Eisenhower signed the Federal-Aid Highway Act, which created the Interstate highway system. The prospect of oil depletion evidently did not have great political salience at the time.

The changed shortly after the 1970 peak, with the coming of the twin energy crises of the 1970s. The United States had been a net oil importer since at least the late 1940s, but the gap between imports and exports grew in the 1960s, and this came to be perceived as a crisis when the price of oil nearly tripled after the OPEC oil embargo. Every U.S. president from Richard Nixon to Barack Obama decried foreign oil dependence and pledged to reverse that trend. It got to the point where commentators grew cynical of energy independence pledges.

But then it happened. Starting in 2009, the United States reversed the long-term trend of declining oil production. The peak in 1970 occurred at 9.6 million barrels per day (mb/d), declining to 5.0 md/b in 2008, and shattering the old peak to reach a value of 12.9 mb/d in 2023, a new high so far. The United States became a net exporter of crude oil in 2020 and remains so up through 2023. The development of Alaska’s North Slope oil fields helped. While the discovery and development of the North Slope predated the 1973 crisis, Hervey (1994) recounts that that high prices aided production.

New technology in later years would dramatically alter reality from Hubbert’s forecast. Analysis from the Cambridge Energy Research Associates in 2006 indicates that, while U.S. oil production had declined to that time, it was 66% higher in 2005 than forecast by Hubbert. More dramatically, Hubbert failed to forecast the increase in production from 2009, which was driven by new technologies such as hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. The advent of fracking owes no small credit to the Eastern Gas Shales Project (1976-1992), a joint venture between the Department of Energy and the private sector. This is an illustration of how high prices lead directly to innovations that increase production, and forecasts that fail to account for this dynamic will surely be too pessimistic.

Some researchers, such as Priest (2014), salvage Hubbert’s predictions by applying it to “conventional” oil and arguing that the forecast does not apply to unconventional oil such as deepwater oil or oil produced from hydraulic fracturing. But this move abstracts away the most fundamental reason why resource shortage forecasts such as Hubbert’s tend to be too pessimistic: they fail to account for the role of new technology.

The Peak Oil Idea

I would date the modern peak oil movement to Campbell and Laherrère (1998), “The End of Cheap Oil”. This short editorial in Scientific American alleges that many of the world’s oil reserve claims are inflated, and that about 1 trillion barrels of oil were either in reserve (850 billion) or yet to be discovered (150 billion) at that time. In contrast, 800 billion barrels had been produced so far. The editorial posits a mechanism by which a peak and decline would occur: the easiest oil is produced first, and later oil requires a high level of capital investment to maintain a flow. Following the idea of a normal curve, Campbell and Laherrère forecast a peak with the simple methodology that in a normal curve, the peak should occur at the midpoint of cumulative production. They forecast a peak to occur no later than 2010. The editorial calls for rapid investment in alternative energy sources, such as nuclear power and synthetic fuels from natural gas, to forestall economic catastrophe.

The 1998 paper came at a time when the price of oil was at a low point of around $10 per barrel and the world was fairly peaceful, or at least appeared to be. It was a good time to get in on the ground floor of the movement. The previous year, Campbell had written a piece in the Oil & Gas Journal warning not only that peak oil was soon, but that it would have dire consequences for the world economy.

Deffeyes (2001) forecast peak oil in 2005 and no later than 2009. Deffeyes imagines that new technology, spurred by the high prices that peak oil would no doubt bring about, would soften the decline, but the peak date was too soon in the future for new technology to significantly alter it. Deffeyes’ estimates of proven and probable reserves are similar to those of Campbell and Laherrère (1998).

Half Gone (Leggett (2006)) forecasts peak oil from 2005 to 2015. A dismissive piece from OPEC notes that Matthew Simmons, author of Twilight in the Desert on Saudi Arabia’s alleged oil production problems, suggested in 2006 that world peak oil may have already passed in 2005. In 2011, Fatih Birol, who was then the International Energy Agency’s chief economist and now the executive director, asserted that peak oil had occurred in 2006.

The Peak Oil Movement

The peak oil movement spawned much more than a few academic papers and predictions. Colin Campbell, an author on an above-mentioned paper, founded the Association for the Study of Peak Oil in 2001, with the first International Workshop on Oil Depletion the following year. In the mid-2000s, the issues found its way back into the popular press, such as with the September 21, 2004 Wall Street Journal article entitled “As Prices Soar, Doomsayers Provoke Debate on Oil's Future”, prominently featuring Colin Campbell’s work.

The Oil Drum, a project of ASPO, became a leading source of detailed information about peak oil. It published content from 2005 to 2013, and then remained as an archive before closing entirely in 2016. I read The Oil Drum for much of that time. Despite an ideological orientation that I no longer share and much information that in retrospect was clearly faulty, I found The Oil Drum to be one of the best-written and most comprehensive specialty news sites on any topic I have ever been interested in.

The peak oil idea came deeper into the mainstream in 2005 with the publication of the Hirsch report, commissioned by the U.S. Department of Energy, entitled “Peaking of World Oil Production: Impacts, Mitigation, and Risk Management”. The report forecast a peak of world oil production by 2015 and concluded that a concerted effort to develop alternative energy sources would take at least 20 years to bear fruit. This leaves at least 10 years of economic disruption between the peak and alternatives coming online.

After Y2K and before the 2012 phenomenon, imagined economic disruptions from peak oil were the nucleus of apocalyptic fears in the survivalist community, as documents Schneider-Mayerson (2015). The same author (Schneider-Mayerson (2013)) found peak oil, and environmental influences more broadly, in many of the disaster movies of the 1990s and 2000s.

Peak oil also became the nucleus of hope for the destruction of socioeconomic systems that are perceived to be harmful. Holmgren (2002), an advocate of permaculture, sees energy descent resulting from peak oil and forced climate change mitigation as a catalyst for permaculture, which he argues is more natural, healthier, and more ethical than the industrialized agricultural system that prevails today. Peak oil also served as a catalyst for the formation of the Transition Towns movement in 2005, a grassroots movement to build more autonomous and resilient cities.

Of course, as a Malthusian ideology, peak oil attracted interest from the uglier side of that movement. Duncan (2001), “World Energy Production, Population Growth, and the Road to the Olduvai Gorge”, takes its title as reference to an archeological site and posits that industrial civilization has a 100 year lifespan, from 1930-2030 (one can quibble about the start date as much as the end date), and it argues that peak oil will result in nothing less than the destruction of industrial civilization. The movement was very much associated with population control and anti-immigration.

The obvious fuel for the peak oil movement was rising oil prices, which also manifested as rising gasoline prices, something very visible to the public. The price of crude oil rose to what seemed like an alarmingly high level of $40/barrel in 2004, and it kept rising to a high of $147/barrel in July 2008, a record which still holds despite a decade and a half of inflation. Two months later, Lehman Brothers collapsed, bringing the global financial crisis into full swing. Unlike the economy, though, interest in peak oil never recovered.

Aftermath

The Oil Drum and ASPO, once key institutions in the peak oil world, are now defunct. Others, such as the Transition Towns movement, are clearly not what they used to be. Many people who were involved with the peak oil movement, such as Joe Romm and Chris Nelder, have moved on to other topics, and others are now simply off the public stage.

The peak oil concept has been repurposed as “peak oil demand”. The International Energy Agency, for instance, projects that oil production will peak by 2030, not as a result of supply shortage, but as a result of diminishing demand due to slowing of economies, cheaper alternatives, and concerns about the environmental impacts of fossil fuels. We shall see if these predictions do better than the supply predictions. Meanwhile, climate change has become by far the dominant environmental issue, falling birth rates have replaced overpopulation as the leading demographic anxiety, and artificial intelligence leads for apocalyptic fears.

Peak oil still has die-hard advocates. Bardi (2019) assesses that the predictions of the movement were largely correct, though obviously the specific date and level of the peak were overly pessimistic. He assesses that the normal curve for annual oil production for a region is correct, though I don’t follow his logic. The Soviet Union/Russia has shown a bimodal production curve due to political disruption, and the United States has due to the widespread use of new technology from the late 2000s. He seems to present the superposition of multiple bell curves as validating the bell curve model, which appears to me to be nonsense. Anything can be presented as a bell curve if we accept that. Bardi believes that the real reason peak oil has faded from the mainstream discussion is that it comes across as a “doomer” idea that people don’t like.

The perception of the peak oil model being wrong is one that I share. The problem is not simply the sensationalist grifters that gravitated to the idea, but with the idea itself. Every Malthusian idea that I have come across makes the same mistakes: they fail to account for new technology, and they fail to incorporate economic feedbacks from shortages and high prices. These problems should have been obvious to anyone who is familiar with The Limits to Growth or any other Malthusian idea.

Still, during the movement’s heyday, I was a believer. At least in my case, the flaws of Malthusian thinking needed to be learned the hard way. Peak oil may be dead, but I fully expect that the idea will be reincarnated in a few years so that the next generation can learn the same bitter lessons the hard way.

Finally, some comment on the movement’s psychology is in order, though the following are strictly my own observations. I strongly suspect that one reason that so many people followed the movement for so long, in spite of the idea’s glaring problems, is that at some level, they wanted it to be true. There are political extremists who see modern industrial civilization, or even human society as a whole, as so corrupt that they wish for its destruction, or people who are simply bored with punching a clock at a warehouse. These are things that I have noticed with many other apocalyptic movements, and especially with those people who bounce from one movement to another as though the old one never happened. My hope, then, is that we at least might learn something from the bad ideas of the recent past.

Quick Hits

In response to last week’s post, a reader pointed out a flaw in my thought experiment. The idea of fully colonizing the Virgo Supercluster in 6400 years, the time it might take to exhaust the supercluster’s resources at a growth rate of 1% per year, is impossible because we assumed adherence to established physics and the Virgo Supercluster has a diameter of 110 million light years. While this doesn’t affect the point that I was trying to make—perceptible exponential growth will exhaust any conceivable resource base on time frames relevant to human civilization—I do appreciate the need for accuracy.

At Vox, Marina Bolotnikova assesses the flaws in the “ultra-processed foods” concept. The term derives from Monteiro et al. (2009) and has since then been used in some other papers. The problem, as the Vox article highlights, is that UPF is only a proxy, and a rather poor proxy at that, for things that we know are unhealthy, such as high sodium, sugar, and fat content. I don’t think it will be long before UPF, and the Nova classification system on which it is based, loses whatever scientific credibility it has like the anti-GMO movement did.

Following the outer of the Assad regime in Syria, mass graves has been discovered containing at least 120,000 victims. Near Damascus, the Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reports that 80,000 disappeared people have been found dead, with 60,000 people having been killed by torture. How much more barbarism from the Assad rule will be found is anyone’s guess, but we can hope at least that this process will be part of that war-torn country’s healing process. Sadly, Bashar al-Assad is living it up, protected by another criminal regime, and will not face justice as Saddam Hussein did.

On this admittedly unpleasant note, I hope you all had a good 2024. I can say that I did. By the way, did you know that 2025 is a perfect square (2025 = 45×45)? It is the first perfect square year since 1936 and the last until 2116. It still seems like we just celebrated the start of the 21st century, and now we’re a quarter of the way through it. Anyway, I have many plans in store for the Scaling in Human Societies project for 2025 and am looking forward to getting to work on them, and so I will see you then.

An excellent analysis of the Peak Oil hypothesis and movement. I was also a believer in the early 2000s and learned its incorrect assumptions as you did.

My father was a petroleum geologist in the USGS, so I can attest that the theory was very widely believed even among experts in the field.