Thoughts for March 18, 2023

Iraq War, Defense Budget, Energy Superabundance

Good afternoon. It only took me a little more than a year to figure use the subtitle to list topics.

Iraq War

It was on March 20, 2003, 20 years before Monday, that the United States, along with the UK, Australia, and Poland, launched an invasion of Iraq. This would be a good time to look back.

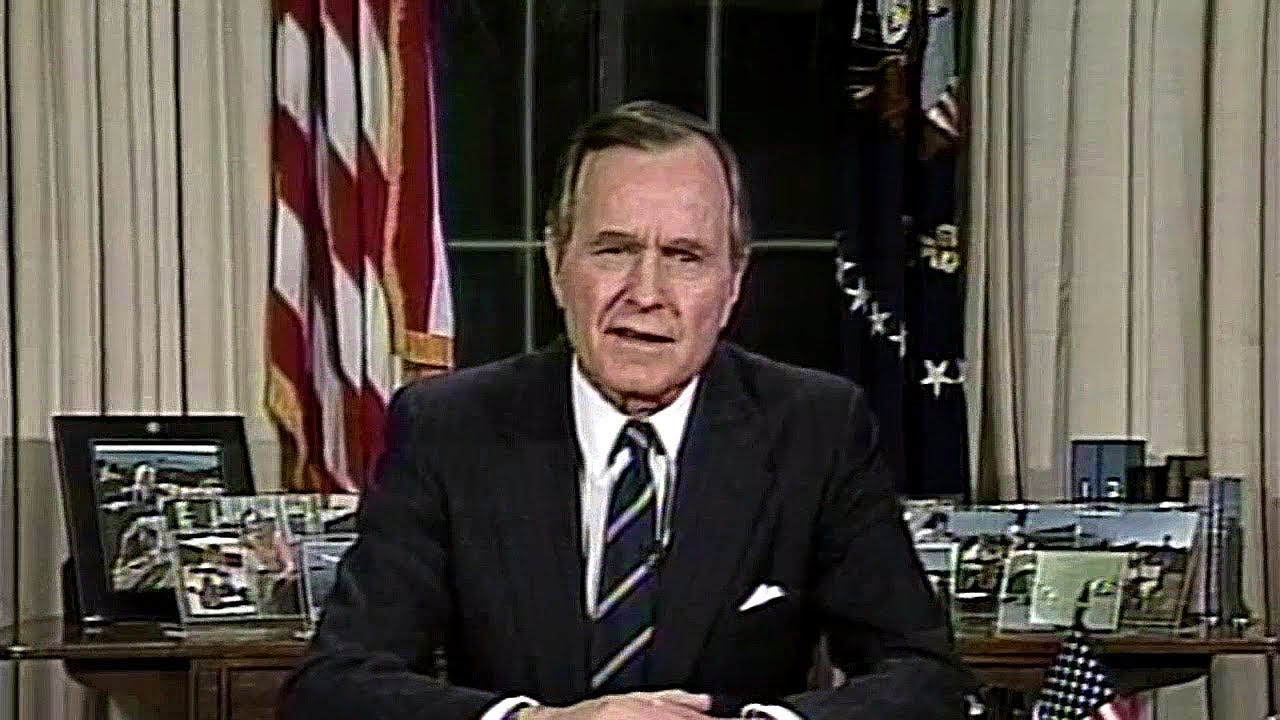

It is important to remember the political atmosphere at the time. Following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the United States organized a coalition to defend Saudi Arabia and liberate Kuwait, first in Operation DESERT SHIELD and then Operation DESERT STORM. The latter consisted of an air campaign against Iraqi radar sites, followed by a ground war against the Iraqi Republican Guard units in Kuwait. The operation was a decisive coalition victory, and it halted the invasion.

Following DESERT STORM, President George H. W. Bush made the decision to end the war and not attempt to depose Saddam Hussein. The decision was controversial, but there was clear logic to it. Overthrowing the Iraqi government and installing a new one would have split the coalition, would have been logistically difficult and costly, and would have caused difficulty with Turkey, a NATO ally, over Kurdish rebellion. But this decision would cause problems for the United States over the next 12 years.

The Iraqi government had conducted genocide against the Kurdish population, with the worst killing in 1988. More massacres occurred after a 1991 uprising against Saddam. The Bush administration has been accused of encouraging, then abandoning, those uprisings and thus sharing in the blame for the massacres. During the Gulf War and for 13 years thereafter, the UN Security Council imposed sanctions on Iraq, with severe humanitarian consequences and questionable effectiveness. The U.S. conducted several attacks against Iraq during that time, including in January 1993 due to Iraqi violation of the No-Fly Zone and fears they may attempt to reinvade Kuwait, in June 1993 after an attempted assassination against George H. W. Bush, in September 1996 in response to the central government’s offensive against the Kurds, in December 1998 for violating UN Security Council resolutions against developing weapons of mass destruction, and in February 2001 for again violating the No-Fly Zone.

In 1997, the Project for a New American Century was founded and released a Statement of Principles, which advocated

•We need to increase defense spending significantly if we are to carry out our global responsibilities today and modernize our armed forces for the future;

• We need to strengthen our ties to democratic allies and to challenge regimes hostile to our interests and values;

• We need to promote the cause of political and economic freedom abroad;

• We need to accept responsibility for America's unique role in preserving and extending an international order friendly to our security, our prosperity, and our principles.

PNAC became a leader in the neoconservative movement, which had a great interest in deposing Saddam from the second term of the Clinton administration, as well as unilateral action broadly, increased defense spending, and missile defense. Leading neoconservatives were appointed to prominent positions in the George W. Bush administration, and following the September 11 attacks, they had their chance to make a major imprint on foreign policy. Bush’s 2002 National Security Strategy outlined his goals of promoting democracy and preventing Iraq from acquiring weapons of mass destruction. The NSS linked state sponsorship of terrorism with efforts to acquire WMDs and outlined the doctrine of preemptive warfare.

Although the Iraqi WMD claims have been discredited, they were plausible at the time, and the notion that Bush officials “lied” about WMDs is exaggerated. Saddam had violated numerous UN Security Council resolutions demanding verifiable disarmament, and Security Council Resolution 1441, passed unanimously by the Security Council in November 2002, offered a final chance to comply. Nevertheless, the U.S. intelligence behind the WMD claims was clearly wrong and the result of errors of reasoning.

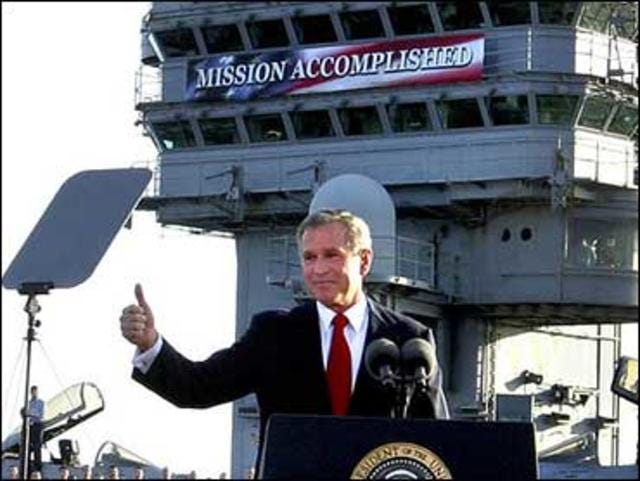

The invasion was a rout, deposing Saddam within three weeks, but only afterwards did major problems develop. There were many mistakes made in the conduct of the war, but two stand out. First, Paul Bremmer, as head of the interim Iraqi government, made two grave errors that created a power vacuum into which the insurgency could grow: de-Ba’athification, or removal of all senior officials in Saddam’s Ba’ath Party from civil service positions; and second, the disbanding of the Iraqi military.

The second mistake was the military’s initial hands-off policy to the deteriorating security situation, starting with Donald Rumsfeld’s “freedom's untidy” reaction to the looting in April 2003. These factors, along with the mismanagement of Prime Minister Nouri al-Malaki, helped lead to the insurgency and the civil war. Only with the Sahwa (Sons of Iraq) program and the troop surge did the situation start to turn around. U.S. troops withdrew in 2011, but later returned to fight the Islamic State.

In identifying what went wrong, the easiest answer would be that the United States should not have invaded Iraq in the first place. But I would posit two other answers to why the war turned into the strategic and political disaster that it did. First, it is clear that the Bush administration had not thought through some basic questions about what post-war Iraq would look like, as well as holding unrealistic expectations of democratization in Iraq. The country is now considered “Not Free” by Freedom House.

The second problem is the extent to which the war, and American foreign policy more broadly, was politicized. There was Bush’s infamous “Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists”, and then there was this from Bill O’Reilly:

Once the war against Saddam Hussein begins, we expect every American to support our military, and if you can’t do that, just shut up. Americans, and indeed our foreign allies who actively work against our military once the war is underway, will be considered enemies of the state by me. Just fair warning to you, Barbara Streisand and others who see the world as you do. I don’t want to demonize anyone, but anyone who hurts this country in a time like this, well. Let’s just say you will be spotlighted.

In some particularly notorious politicking, in Georgia’s 2002 Senate race, Saxby Chambliss ran an ad insinuating that his opponent, Max Cleland, who had been wounded in Vietnam, was disloyal to the United States.

Republicans scored victories in 2002, one of the few instances in which the president’s party gained seats in both houses of Congress in the midterm elections, and Bush won a more decisive victory in 2004 than in 2000. But whatever the short term benefits of politicizing national defense, it meant that when things started to go south, fair weather supporters would quickly bail. Republicans did badly in the 2006 midterms and the 2008 election. This is after a majority of Senate Democrats, and almost half of House Democrats, voted for the authorization of the use of force.

Given the atmosphere immediately post-9/11, it is interesting that in 2008, Democrats nominated a presidential candidate who ran on having opposed the war at the time. It is more interesting that in 2016, Republicans nominated a candidate who (at least claimed to have) opposed the war at the time. And it is even more interesting that in 2016 and 2020, Democrats nominated candidates who voted for authorization. Not because they changed their mind, but because the war had ceased to be salient to primary voters. Such is the depths of isolationism in the United States today, and bad experiences in Iraq have more to do with this than any other factor. Though the debacle in Afghanistan in 2021 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 may be changing things.

Recent commentary is decisively negative. Reason skewers the war as a major mistake, and Eli Lake offers only a tepid justification. But is the negativity fully justified? Iraq’s president Abdul Latif Rashid argues that most Iraqis are grateful that Saddam Hussein is gone. People forget just how bad Saddam was. It is also a mistake to blame the insurgency and civil war entirely on the invasion. Saddam presided over a Sunni government, which was the minority against a Shiite majority, and had brutally put down Shiite rebellions. To blame the invasion for the violence is to argue for severe repression to maintain peace, a position that I don’t think is tenable. Finally, though it is hard to determine counterfactuals, one wonders how different the outcome might have been if the coalition had not made the major mistakes outlined above.

One lesson I take from the war is that the public evaluates policy on how it turned out. Thus, from a political perspective at least, doing things right is more important than doing the right things.

Defense Budget

Now turning to contemporary defense issues, the Biden administration recently released its FY24 budget proposal. The budget includes $842 billion for defense. This is a 3.2% increase over FY23 levels. Given that forecasts predict (rather optimistically) a 3.3% inflation rate for the coming years, the defense proposal is for flat spending, not an increase.

The Missile Defense Agency is requesting $10.9 billion, basically flat in real terms from the $10.5 billion this year, despite

“Missile threats continue to increase, growing more numerous and complex,” MDA’s budget overview released today explains. “Adversary missile systems are becoming more mobile, survivable, reliable and accurate, while also achieving longer rangers. Hypersonic glide vehicles delivered by missile boosters are an emerging threat that pose new challenges to missile defense systems.”

Though it looks like amphibious warships, not included in the budget proposal, will be the biggest item to argue over.

As discussed a few weeks ago, U.S. military spending is heavy on capability (new technology) and light on capacity (breadth of production). The imbalance is still there, but the budget does include a 19% increase in spending on munitions. Mike McChord admits the problem.

We are moving into the multi-year space on munitions in a way that we have not done before. In the past, it was considered that you would buy munitions in much higher quantities generally than airplanes and ships so multi-years weren’t necessary and weren’t done. But we have still found the industrial base is not where it needs to be on this front.

There was an article recently in the Wall Street Journal that drives the point home: the U.S. is struggling to maintain adequate ammunition stockpiles in the face of supplies to Ukraine. How then will enough be produced for a direct war, especially with China?

Here’s an inventory of what the U.S. has supplied Ukraine since Russia’s first invasion in 2014, though I think most of these numbers have been accumulated since February 2022. Supplies include over 1 million 155mm artillery rounds. The Defense Department is working with contractors to increase production of artillery rounds.

Army Secretary Christine Wormuth separately told reporters that the U.S. will go from making 14,000 155mm shells each month to 20,000 by the spring and 40,000 by 2025.

A tripling of production in two years sounds impressive, but 40,000 a month is equivalent to 480,000 per year, still half of the million that have been provided to Ukraine so far (assuming that is also over a year).

Incidentally, the Pentagon recently used the Defense Production Act to speed production of hypersonic missiles and rather dubiously for clean energy technologies, and while the DPA has been suggested specifically for the types of equipment going to Ukraine, I am not aware of this having actually been done.

This is just a quick glance at a few components of the defense budget. There are some good signs, but overall, I don’t see this proposal as reflecting the seriousness demanded by present national security challenges.

Energy Superabundance

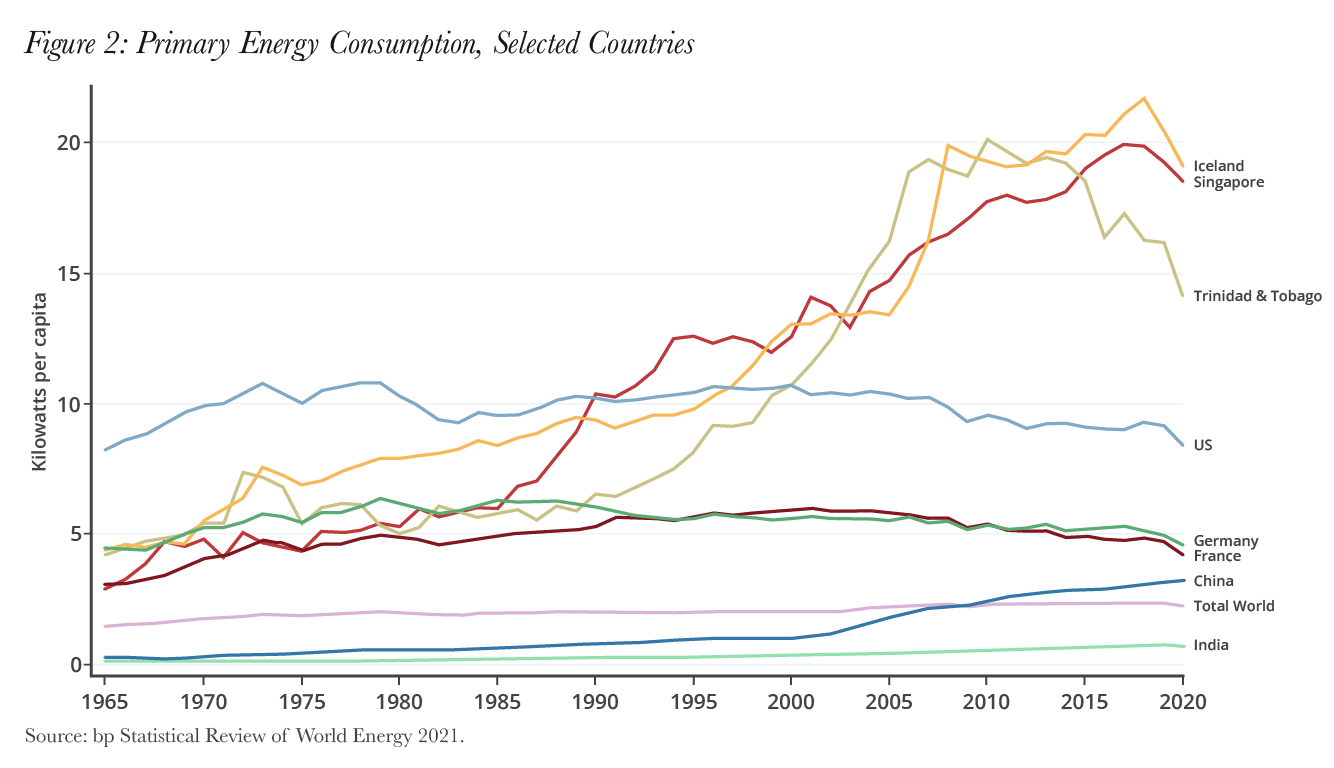

Austin Vernon and Eli Dourado at the Center for Growth and Opportunity have written an interesting piece on energy superabundance. By this they mean,

In this policy paper, authors Austin Vernon and Eli Dourado explore what life would be like with endless energy. Coining the term “energy superabundance,” they look at energy policy, not in the usual sense of trying to restrict energy consumption, but as a way to promote energy abundance—a future in which energy is so clean and plentiful, limiting consumption would be entirely unnecessary.

This is not the way energy policy is pursued now, and it shows in the track record.

The report proceeds apply energy superabundance to transportation, agriculture, water provision, steel and cement, new city development (enabled by transportation), and leapfrogging infrastructure in low-income countries.

The report is interesting, though I have a lot of questions about how realistic the concepts are. For each concept, it would be nice if they made a rough guess of the energy price (electricity price, I presume) that would be necessary, how much energy would be needed, and what sources could supply it. Also, what kind of non-energy advances would also be necessary, as there are many? For example, they discuss last-mile deliveries (drones and sidewalk bots) and electric and autonomous trucking. I don’t think energy prices are a bottleneck to these things.

Regardless of details, there is a need for more creativity in how we imagine the future.