Thoughts for November 20, 2022

Good evening. Topics this week are environmental impacts of desalination, drug policy, hunting and conservation, and defense priorities.

Environmental Impacts of Desalination

Desalination is the practice of taking water unsuitable for drinking or other uses (salty sea water or inland brine) and processing it in a way that it is usable. A few water-stressed regions, such as in the Middle East, South Africa, and California, use desal heavily. But the environmental impacts of desal are controversial. Here I want take a closer look.

Several environmental issues are raised with regard to desal, but the three biggest are (i) energy usage, (ii) entrapment and entrainment of organisms though water intake, and (iii) impacts of brine disposal.

On energy usage, reverse osmosis, the most common desal technique, requires 3.5-5.0 kWh per cubic meter. California uses on average 95 billion cubic meters of water per year, so if that entire supply were to come from desal, that’s about 320-480 TWh of electricity per year. California used 278 TWh of electricity in 2021, so the load from desal would be quite hefty but doable. Keep in mind that meeting 100% of water demand from desal is far more than would conceivably make sense.

On entrapment and entrainment, the WaterReuse Association—a trade group representing companies involved with water recycling and desal—wrote this report in 2011. The analysis is based on a desal plant in California which intakes 110 million gallons per day of sea water and produces 50 million gallons per day of fresh water. That’s a ratio of 2.2; most of what I have seen puts the ratio between 2.0 and 2.5. Based on power plants on the California coast with once-through cooling, this plant impinges 2 pounds of wildlife per day. By comparison, a pelican eats up to 4 pounds of food per day. They also look at entrainment of fish eggs and find that the desal plant entrains 235 million fish larvae per year, which sounds like a lot, but given that fish lay many thousands of eggs, is the equivalent of five adult halibut (n.b. there are some points in this analysis that confuse me, and I am reporting the figures as are).

Back to California, if all water were supplied from desal, 1378 plants like the one described above would be needed. The impact would be 1250 kilograms of wildlife per day impinged—the equivalent of about 700 pelicans’ diets—and fish egg impingement equivalent to 6500 adult halibut. Something may be missing here, but these impacts seem very modest in comparison to the benefits.

On brine, as noted above, desal produces 1-1.5 cubic meters of brine for every cubic meter of fresh water. Environmental concerns are that brine is at a higher temperature than ambient water, the salinity impact on sea life, decrease of dissolved oxygen, and lowering of pH. I haven’t yet found a good quantitative representation of the impact, however.

Several environmental approaches, such as that mentioned above, treat desal as in opposition to efficiency, conservation, and recycling, and oppose it on those grounds. That’s the wrong approach. The right approach is a comprehensive strategy such as that which Israel uses. The strategy entails the National Water Carrier to deal with the nation’s unevenly distributed supply; drip agriculture, which Israel invented; recycling rates of treated water and stormwater that are the highest in the world by far; and desalination; among other strategies. There is no good reason why these strategies should be placed in opposition to each other.

Even more absurd is the use of the threat of water scarcity as a pretext for population control, as e.g. Peter Gleick does. I roll my eyes as population control in general, but it especially ridiculous in the context of water supplies, as water access is an easily solvable issue.

Drug Policy

Right now, there is considerable movement toward decriminalization of illegal drugs. Decriminalization might retain fines or other civil penalties for drug use, but would remove criminal penalties such as prison time. Decriminalization might also retain criminal penalties for distribution of drugs rather than usage. A larger step would be full legalization. This is a complex issue, and I am still trying to wrap my mind around it.

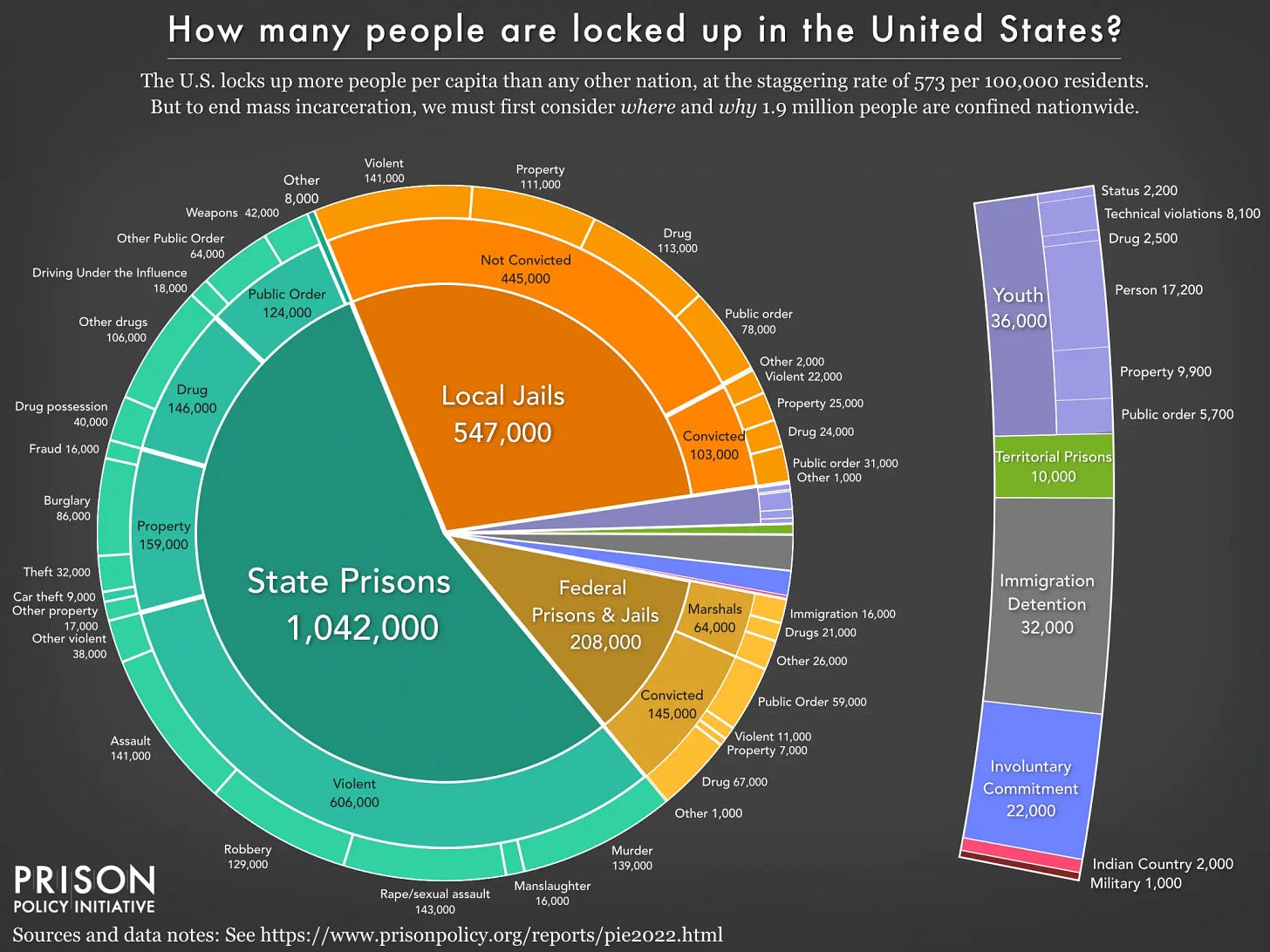

About 20% of all people currently incarcerated in the United States are incarcerated on drug charges, including people who are in jails and have not (yet) been convicted.

Mass incarceration in the United States is a complicated issue. Whatever the merits of drug decriminalization, that is not a quick fix to the problem. Though one thing this chart doesn’t make clear is how many people are incarcerated for multiple crimes, or how drug use/criminalization plays into other crimes.

Basic economic reasoning suggests that under decriminalization/legalization, the price of drug use as experienced by the user goes down, so the amount of use should go up. It looks like the empirical evidence supports this but is mixed. This paper does not find a significant increase is drug use in Portugal after decriminalization in 2001, though it should be noted that the practical effects of decriminalization in Portugal were more modest than often imagined because even prior to 2001, the legal regime had been weakening, and Portugal retained criminal penalties for distribution after 2001. Here is some evidence that drug-related deaths did increase in Portugal after 2001, and also in Italy after they decriminalized. Marijuana use in Colorado increased after decriminalization.

There are three anti-trafficking international agreements, to which most countries in the world are a party, that would have to be considered in any major decriminalization/legalization effort.

Here’s the 2021 UN World Drug Report. They find that 275 million people (out of about 8 billion) use illegal drugs, with 200 million cannabis users. They say there are 30 million people with “drug use disorders”. Drug use cost 500,000 lives and 30 million disability-adjusted life-years in 2019.

Despite common beliefs, it is not correct that cannabis is harmless. Cannabis contributes to car crashes, and overdose deaths/injuries have been observed. There is also a risk of long-term costs to brain health, especially among adolescents. These risks should be considered alongside health benefits of medical marijuana.

We should be careful not to lump all decriminalization policies together, as the appropriate treatment of, for example, cannabis, heroin, and cocaine might be very different. For that matter, we have drugs—alcohol and tobacco—which are mostly legal but highly regulated around the world, and we can ask whether this is the most appropriate regime for them. Decriminalization also plays deeply into questions of personal freedom that cannot be readily resolved by statistics. Whatever the solution is, it should be informed by good data.

Hunting and Conservation

Hunting and conservation are two activities that may seem to be at odds with each other, but they are tried up due to financial decisions.

It is commonly believed that hunters in the United States, through taxes and licensing fees, pay for most conservation. This is not really true. A study by the Mountain Lion Foundation found that hunters paid 6.1% of federal and philanthropic conservation funds, and much of that is from general tax revenue which hunters pay by virtue of being citizens, and which has nothing to do with hunting.

This report doesn’t discuss state conservation though. They find $1.3 billion come from hunters for federal and private conservation; there is an additional $800 million for state programs that comes mostly through license fees. The dependence is sufficiently great that states are worried about the decline in hunting and conduct R3 (Recruit, Retain, and Reactivate) programs to increase hunting.

The political economy behind such arrangements is easy to imagine. Using hunting licenses and taxes such as those of the Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson Acts allows hunters to portray themselves as a positive environmental force, and it creates a broader constituency for hunting. One sees similar calculations at work with arrangements such as state lotteries for education for cigarette taxes for CHIP. But these dedicated tax arrangements also get policy trapped in local optima.

Defense Priorities

Mackenzie Eaglen has a useful editorial on what she sees as an excessive prioritization of capability over capacity in the U.S. defense posture. In defense jargon, capacity refers to the overall size of a military force, while capability refers to its technological prowess. Given a fixed budget, there is a tradeoff between the two, as one can choose to investment more of the budget on expansion of personnel and acquiring more equipment today, or more of the budget on R&D for future equipment.

The editorial discusses the issue mostly in the context of the risk that China would attack Taiwan. Given China’s long-term economic and demographic challenges, I expect that if such an invasion occurs at all, it will occur in the 2020s. Furthermore, U.S. supplies to Ukraine has and will continue to deplete equipment stocks, which need to be rebuilt.

This occurs at a time when the procurement to R&D ratio is at a low value, currently 1.11:1. The ratio was 2.74:1 during the Reagan arms buildup, and Eaglen suggests a value of 2.25:1 as appropriate. U.S. military spending was about $800 billion in 2021. Moving the ratio from 1.11:1 to 2:25:1 would entail shifting about $130 billion from R&D to procurement if overall spending remains fixed, or (as I think is more appropriate), increasing procurement spending by $430 billion if R&D spending is held constant. That would increase overall spending spending to $1.23 trillion. This increase would put the defense budget, as a percentage of GDP, below the level of the Reagan arms buildup, and well below that of the early Cold War period.

Not knowing the intricacies of defense spending, two considerations come to mind. First, Eaglen discusses that on the personnel side, the Army, Navy, and Air Force all fell well short of their recruiting goals. She portrays this as a problem with the budget. But the condition is reminiscent of anecdotal reports of labor shortages in a wide range of industries, and with population aging expected to continue for the foreseeable future, it should be understood that the military, like everyone else, is going to have to adapt with more labor efficiency. Additionally, the same condition of population aging places greater demands on Social Security and Medicare, and defense budgets at the level seen from World War II to the end of the Cold War will be difficult to achieve. These considerations suggest that a focus on capability is appropriate.

On the other hand, I’ve observed from nuclear power and other industries that capacity is capability to a large extent. While some nuclear advocates suggest small modular reactors, Gen IV reactors, or fusion as the answer to the industry’s stagnation, new technologies will not address issues of supply chains, regulation, a strong workforce, and effective contracting. These will happen only through a focus on deployment today. Likewise, I would wonder that if the U.S. military puts too much focus on technology, that they might not be well equipped to make the best use of that technology when it does arrive. This consideration suggests that a focus on capacity is appropriate.

But what I gather to be the overriding concern from the editorial is that, with the ongoing war in Ukraine and the threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, the 2020s may be a particularly perilous decade. Defense spending would be one area where more of a short-term focus is called for.