Thoughts for July 24, 2022

Hi all. Today’s topics are a revisiting of the labor shortage, decentralization, and ossification of canon in science.

Labor Shortage Redux

Last week I wrote about the common description of a “labor shortage” in the press, supposedly going on right now, and reasons that I am skeptical of this claim. A reader responded with a couple points.

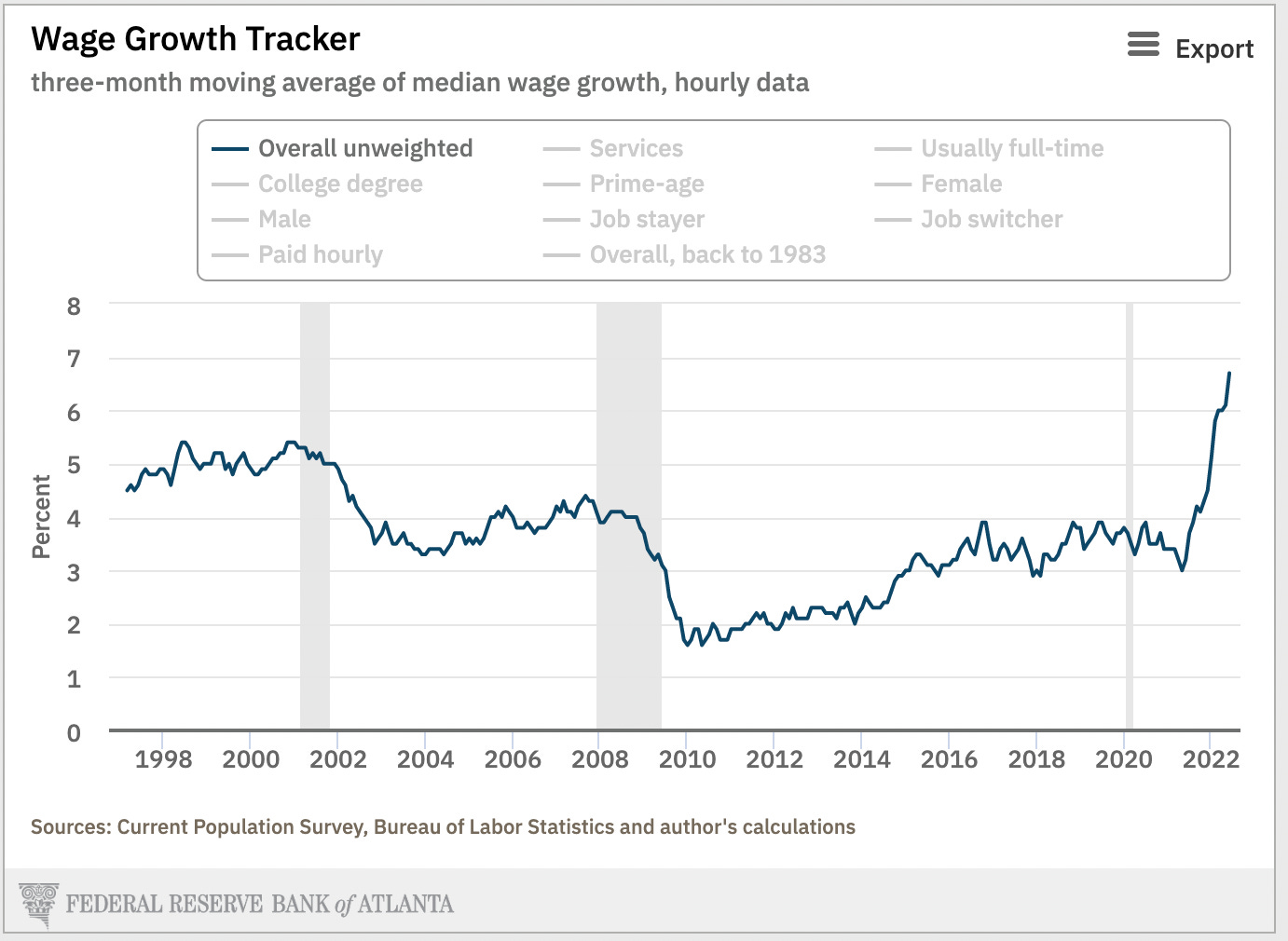

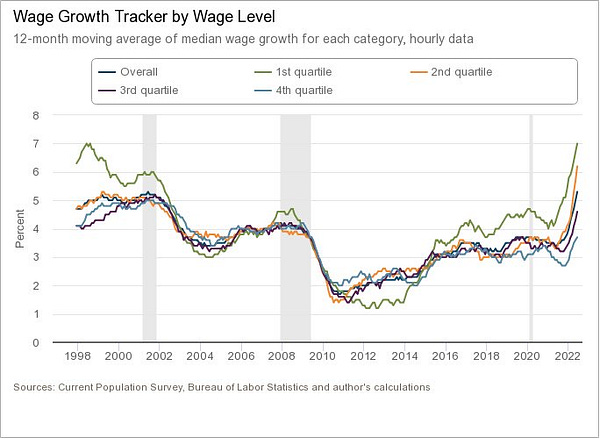

First, he thinks that I cited misleading wage figures and that this data is more relevant.

Unlike the figures I cited last week, these figures do not show a spike in median wages during the height of the COVID shutdowns. Last week’s figures were median wages across all workers, while these figures track the wage growth of individuals who remain in the same occupation. I’m not sure all the statistical details, but it seems to be a more accurate picture of how wages are evolving. It also portrays percentage growth rather than absolute levels, making it easier to see trends. This looks like clear evidence of an improved bargaining position for labor from 2021, until one remembers that these are nominal, not real wages, and that inflation spiked around the same time. I don’t have real wage figures in front of me, but I believe these figures are less than the inflation rate since mid-2021, indicating that real wages have been going down. Again, not what one would expect in a labor shortage.

One nugget of good news, though, is that since 2015 or so, wages for the lowest quartile have been going up faster than than all other quartiles. Given heightened concerns about income inequality, this is a relief.

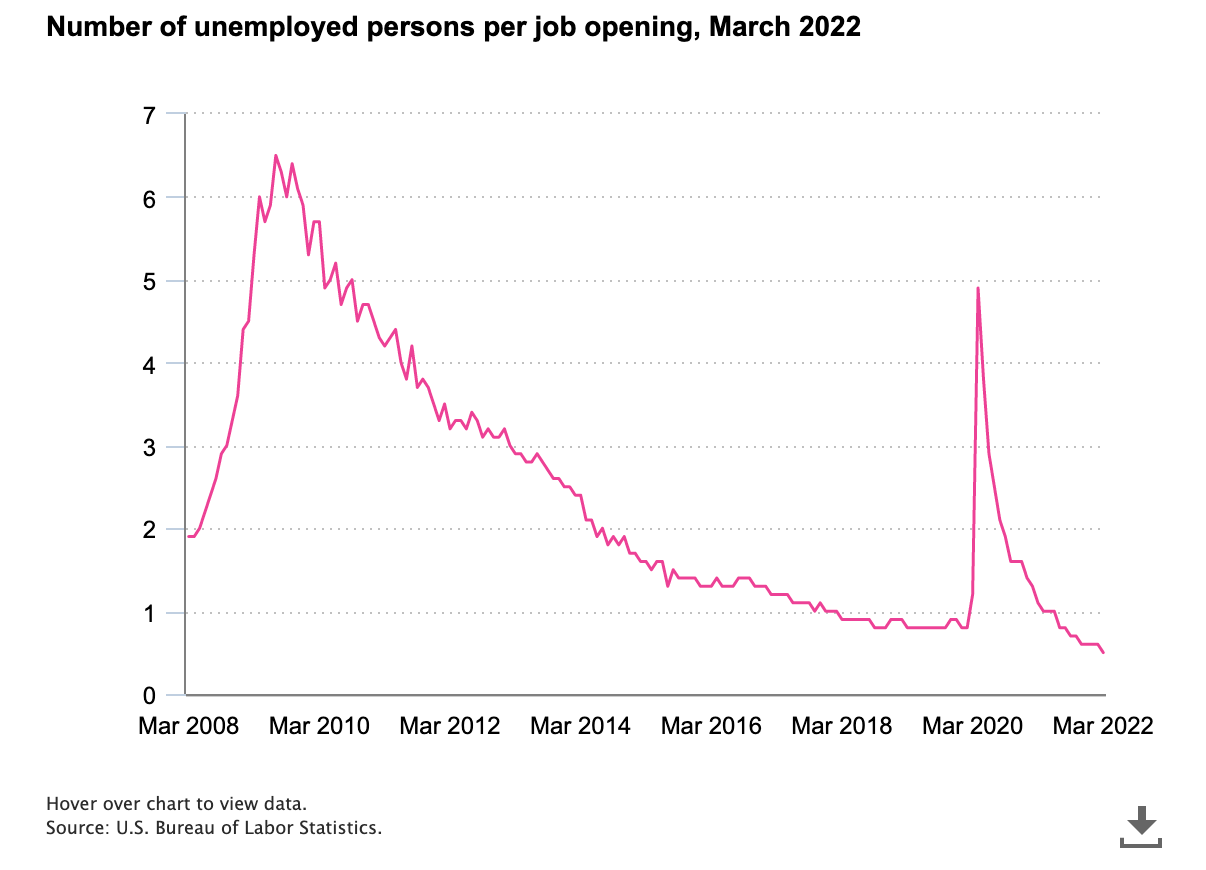

Another point the reader made is that, while the absolute level of the unemployed people to job opening ratio is hard to interpret, the trend is relevant and shows a clear sign of benefiting labor in the last couple years.

Last week, I was dismissive of this statistic on the grounds that “job openings” can be a deceptive measure of the demand for labor. I cited some anecdotal reports of job openings that would presumably count toward these statistics but are not actually open jobs. The reader acknowledges that this may be the case—though it is hard to quantify—but finds it implausible that the phenomenon of fake job postings could have increased so much as to explain most of this decrease. That’s a fair point.

The evidence is admittedly mixed, but I stand by my claim that labor market conditions do not benefit labor to nearly the extent that is often claimed in the press. I also stand by the observation that the phrase “labor shortage” is too subjective to convey meaningful information, and this phrase should be ditched for something more quantifiable and verifiable. One set of related statistics I would like to see, but haven’t been able to find, are some figures on the difficulty of finding/filling openings. How many applications does one typically need to make to get an interview and an offer, how long does a job search typically take, how many applications does an opening typically receive, and how have these figures evolved over time?

The Dream of Decentralization

Since the mid-2000s, production of hearing aids has gone mostly to 3D printing. This paper finds that there was no evidence of a move toward more localized production, as production and trade of hearing aids went up by the same amount since then. They find similar results for a number of other (partially) 3D printed products.

This got me thinking about the myriad ways in which thinkers have imagined that the economy might decentralize, while it hasn’t.

3D printing will replace centralized manufacturing. While 3D printing is growing as a share of manufacturing, as noted above, there is no sign that this is causing decentralization.

Renewable energy will decentralize power production. Writing for The Breakthrough Institute in 2015, Will Boisvert argued that the Tesla Powerwall, the battery system that was in the news at the time, would not decentralize the grid. History has proven this assessment correct. If a major shift toward renewable energy proves to be technically feasible, it would disrupt petrostates and large fossil fuel companies, but it would add new centralization in the form of complex critical mineral supply chains, and further upgrades to grid infrastructure in the form of high voltage transmission and/or storage.

Alternatives to agribusiness. Dread about the role of large corporations in agriculture, such as Monsanto, motivate much of the impulse toward organic agriculture and hostility to genetically modification organisms. Much has been written about the disaster that Sri Lanka’s lurch toward organic farming has been and how widespread organic farming is infeasible. High tech hopes for decentralization have been put on vertical farming, but for now the energy needs are mostly prohibitive. If widespread cheap energy becomes available such as to make vertical farming practical on a large scale, it is not at all clear that the result would be a localization of agriculture. Cheaper energy should also facilitate trade.

Web 2.0 democratizes content creation. Breathless articles such as this one, highlighting how YouTube has democratized video production, already seem comically anachronistic in an era of populist backlash against “Big Tech”, even though their analysis is correct. The trouble is that, while it is certainly much easier to produce and distribute videos today than it was in age of network television dominance, the locus of power has shifted toward those who are able to program services such as YouTube and control the infrastructure. People who don’t like the content moderation policies of social media have few credible alternatives and resort to pushing their case through government regulation.

Web 3.0 will counter the centralizing tendency of Web 2.0. The recent crypto crash has done much to pull the wind out of the sails of this idea. I would remind the reader again of Samo Burja’s argument of the inevitability of Internet centralization. See also Moxie Marlinspike’s analysis.

To my knowledge, history furnishes no example of a major decentralization of power except in times of severe deprivation, such as Europe in the aftermath of the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Hopes that this will happen in the context of prosperity have been dashed, and attempts to do so have met with disaster. There are real problems with centralization, such as greater systemic risk of institutional failure or high housing costs through regional concentration. But any effort to deal with these problems should be based in rigor, not just a romanticization of a decentralized lifestyle.

In some sense, advocates of decentralization can never win, because even if society moves in a direction they hope, they will turn against the institutions that are driving the change when they become the big institutions. Look how fast the progressive left turned against Elon Musk and his companies, or against the “sharing economy”, such as Uber, Lyft, and AirBnB, or how the “techlash” has emerged. I can already hear people objecting to the characterization of a sharing economy, but this was once the hope.

Finally, it has to be questioned whether the concept of de/centralization introduces a false dichotomy. Two major trends since the onset of industrialization have been an increase in personal freedom and a growth of corporate and government power. Both can happen simultaneously because economic growth has brought about an overall increase in human agency, and thus individual agency and corporate agency are not in a zero-sum competition.

Ossification of Canon

There was an interesting paper last year, showing that when scientific fields get large, there tends to be a slowdown of turnover in central ideas, or what they describe as an ossification of canon. This casts light on the much-discussed Bloom et al. Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find. They document falling productivity in research across many fields, and so the amount of spending on science must increase to counterbalance declining productivity. The results of Chu and Evans suggest, though, that falling productivity might be happening precisely because of increased spending.

With public investment into R&D, there is a need for more rigor on how effective the spending actually is. One principle would be to orient public funding more toward novel research. But it appears that incremental research is more likely to be funded instead.