Thoughts for July 17, 2022

Good afternoon. Today’s topics are Sri Lanka, the labor market, and China’s demographics.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, an island nation off the South coast of India, is in the news for a major economic and political meltdown. Protests earlier this month compelled President Rajapaksa to flee the country.

Most examinations of what went wrong begin with the country’s organic agriculture policy. In a move toward making Sri Lanka a fully organic country, the government banned the import of chemical fertilizers. Ted Nordhaus and Saloni Shah explained a few months ago why this has been a disastrous decision. In short, without chemical fertilizer, agricultural yields fell dramatically, which created food shortages and devastated tea exports, an important source of revenue.

Feeding more than a small portion of the world’s population using organic methods is physically impossible. Nitrogen is a necessary ingredient in crop growth, and cutting out nitrogen from the Haber-Bosch process puts hard limits on how much crop can be produced from Earth’s biosphere. Using organic fertilizers, such as manure, don’t get us around this limitation, since the animal feed behind the manure must also have come from synthetic sources. The phenomenon has been called “nitrogen laundering”. Maximizing the use of organic farming, as Sri Lanka attempted to do, would be environmentally devastating. Because yields fall without synthetic fertilizer, more land is required to produce the same amount of food, which means more deforestation and more conversion of wild land.

Still, it would be neglectful to consider Sri Lanka’s crisis without considering other factors. The country suffered a civil war from 1983 to 2009, and since then, there has been considerable violence, particularly major terrorist bombings in 2019. This event, and especially the COVID pandemic the following year, devastated Sri Lanka’s tourist industry and cut deeply into an important source of revenue. This came after years of accumulating a dangerous level of foreign debt, particularly through an overextension of infrastructure projects through China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The debt caused great difficulty with imports—a pretext behind the 2021 fertilizer import ban—and also has caused serious fuel shortages. Visual Capitalist has a brief, useful explanation. On top of that, Sri Lanka’s government is corrupt, and there are serious human rights abuses.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the fertilizer import ban is the cause of Sri Lanka’s problems. Rather, the import ban was one of a series of serious missteps. Defenders of organic agriculture will downplay the importance of the ban, or if they address it at all, consider it a move compelled by the dire foreign debt situation rather than by green ideology. Certainly, by the time the policy was instituted in 2021, Sri Lanka was already in serious financial trouble. But the import ban was a very bad policy. Between this and German Greens supporting the ramping up of coal-burning power, it has been a bad year for the mainline environmental movement.

Labor Shortage

There have been many statements in the press over the last year to the effect that there is a labor shortage in the United States right now. For reasons outlined below, I consider this implausible.

The first thing to get out of the way is that the concept of “shortage” is subjective. “Subjective” doesn’t mean “wrong”, but it means that more context is necessary. For example, above I noted food and fuel shortages in Sri Lanka. This can be quantified by noting rising prices, for instance. According to Economics 101, a shortage does not exist except in the context of a price, and in a free market, if demand exceeds supply of a good at a given price point, the price should rise so that the two are equal. Thus there should not be a true shortage.

Of course, real life doesn’t follow the simplicity of freshman economics textbooks, and shortages can occur for a variety of reasons, ranging from artificial price controls to friction in the market adjusting to changing conditions. Even if there is price equilibrium, we might consider an equilibrium price above what is “expected” to be a shortage. People debate, for instance, whether there is a housing shortage. Such a consideration only adds more subjectivity to the concept, since we now have to parse what market conditions “should” be. For the most part, I find most claims in the popular press about a labor shortage to be so subjective that it is impossible to judge whether they are accurate. But they do admit other grounds for criticism.

See this write-up from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce for a fairly typical overview of labor shortage claims. Read it first if you care to, and I’ll go into some of the ways in which their claims don’t make sense.

The main metric they use to assess a labor shortage, stated at the start of the article, is that there are six million unemployed workers and 11 million job openings. The main problem here is that job openings are not a very reliable measure. Here the Financial Times writes about fake job openings. “Fake” might not be quite the right word; they are more like job openings that a company is not deeply motivated to fill, but they are posted in the hopes of attracting an ideal candidate. Here’s a Reddit thread kvetching about allegedly fake job postings. All this leaves me uncertain how to interpret the Chamber of Commerce’s numbers, and it doesn’t help that they don’t provide any historical data. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that that the unemployed worker to job opening ratio is indeed low now by historical standards, but again, I question the relevance of this metric.)

The Chamber of Commerce notes that labor force participation is down from 63.3% in January 2020 to 62.2% whenever this section was written. Part of that is population aging and a large share of the public being retired. Part of it is the result of short-term factors; the Chamber cites the lack of affordable childcare among others. Still, all else being equal, one would expect labor force participation to go up in the event of a labor shortage, and they don’t make a compelling case that not all else is equal enough to make an appreciable difference.

Last year, there was a common claim that extended unemployment benefits under the CARES Act contributed to the labor shortage. Such claims have gone away now that extended unemployment has gone away, but the alleged labor shortage has not gone away. The claims were never very good to begin with and should not have been given much credence. This paper from 2014 finds that in the 2008-09 recession, extended unemployment benefits increased the unemployment rate by 1/3%—a small fraction of the increase during that time—and did not affect the labor force participation rate, and that the effect was even smaller in previous recessions. This paper finds a “small” disincentive for work as a result of the CARES Act (though I’m not sure what the authors mean by small) and cites some earlier results finding no disincentive effect from similar policies. Recall that some states ended extended benefits earlier than other states. This paper finds a little bit of gain in employment from states that ended early, but the wages from jobs induced in this way were only about 5% of the lost benefits of extended benefits. In short, extended unemployment can explain at best only a small fraction of the alleged labor shortage.

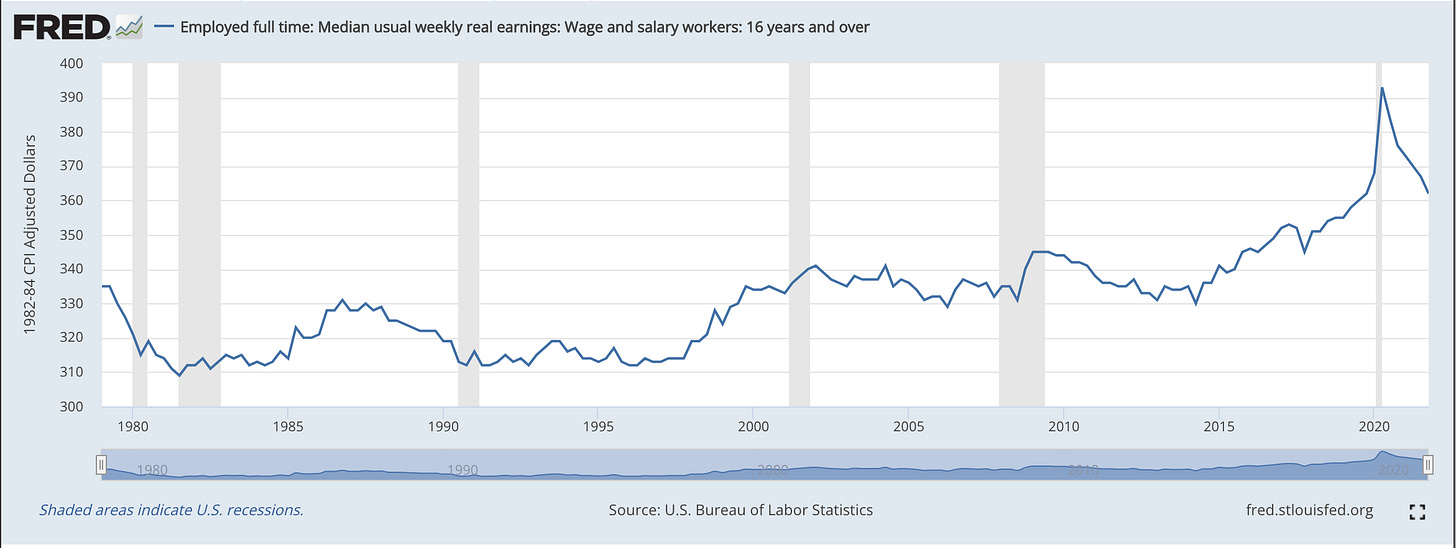

The most compelling evidence against the labor shortage in my view is tepid response on wages.

The spike in 2020 occurred because the layoffs were most prevalent among low-wage workers, raising the median wage even if employed workers didn’t see a raise. The decline in wages after the height of pandemic shutdowns is the same phenomenon, working in reverse. So this data is a little tricky to interpret. But I’m not seeing the decisive increase in real wages that would be expected in a labor shortage. In the June 2020 report, the Bureau of Labor Statistics notes a 0.5% increase in nominal wages from May to June, together with a 1.5% increase in the CPI, leading to a real decrease. They also note a 0.9% decrease in the average workweek, another statistic one would not expect to see in a labor shortage.

The only convincing evidence I can see for a labor shortage is that the unemployment rate is at 3.6%, a low value and about where we were in 2019. Claims of a labor shortage go back to when the unemployment rate was above 6%.

Since most labor shortage articles rely on anecdotal evidence, there is anecdotal evidence against it too. There is a profile of a Florida man who applied for 60 entry level jobs and got no offers. I’ve been running around in various tech-oriented groups for the last few years, and I know no one who found a job as a software engineer, data scientist (supposedly in-demand fields), or something related without considerable difficulty. Someone whose responsibilities include hiring of data scientists told me that they typically get about 100 applications for an entry-level opening, of which 30-40 will be qualified. These numbers are not consistent with there being a shortage.

I was primed to be skeptical of the labor shortage story because I remember well the panic about the STEM worker shortage a few years ago, and how that too turned out to be wrong. I’m not sure why this claim is so widespread when even I, with no training in labor economics or any kind of economics, can easily see flaws. There is a degree of herd mentality and groupthink in journalism, as we saw with Iraqi weapons of mass destruction prior to the 2003 war and the housing bubble in the 2008 recession.

The labor shortage story is also too convenient to pass up. Here’s the Heritage Foundation using the labor shortage as a hook to push some of its policy preferences (I’m not commenting on the merits of these policies, only the way in which they are argued). Many organizations use the labor shortage as an excuse for their shortcomings. Here is TriMet, the Portland Metro area’s transit system, using an operator shortage as an explanation for cutting routes. To be fair, here is also a debunking of the STEM worker shortage a few years ago motivated by opposition to the H1-B visa program.

We once again see, don’t believe something just because it is a widespread belief.

Demographics in China

Last week I discussed demographics in the late Roman empire and the difficult we have in getting a precise handle on the demographic picture. But there are challenges at present times as well. In the case of China, it is because of alleged falsification of statistics. According to the demographer Yi Fuxian, actual population in China is nearly 10% lower than official estimates. Births started to decline in 1991, and population peaked in 2018 rather than the projected 2031. Last year, Fuxian wrote a more extensive editorial on the subject.

Fuxian advocates that China ends the one-child policy, something that they sort of have done but not completely. To that end, there remains considerable debate about what impact the one-child policy has had on the country’s demographics. Daniel Goodkind estimates that as of 2015, the entirety of China’s population control policies had averted 360-520 million births, with the one-child policy in particular having averted 400 million. All estimates are to roughly double by 2060.

Goodkind’s paper was controversial, as detailed in this article. Reading between the lines a bit, the field of demography arose out of postwar population anxiety and had its tone set by what then were worries about overpopulation. The antinatalist tone persists to this day. The human rights abuses that came out of the one-child policy are an embarrassment to the field, and for that reason, most researchers don’t want to “credit” it with having reduced births. This paper is more in that vein. I don’t understand the issues well enough to have a strong opinion about who’s right, but I find it implausible to think that that a coercive population control policy would not have much impact on birth rates.

There are also allegations that China has inflated population numbers in Xinjiang Province in particular to mask the effects of their alleged genocide of the Uyghurs.

China’s year-over-year GDP growth (also suspected of manipulation) was 0.4% in the second quarter, a quite low value relative to recent performance. If the official population figures are correct, then China might still have a few solid years of economic performance left. But if Fuxian’s numbers are correct, they might now have hit a period of chronic economic stagnation, much as Japan did in the 1990s.