September 9, 2023: Defense Spending

Good afternoon. Today we are going to make a brief and, due to the size of the issue, selective tour of defense spending in the United States.

Addendum to Cargo Cults

But first, a reader made the following comments regarding last week’s post on cargo cults.

The concept of Cargo Cults is definitely fascinating - going along and copying things with little understanding of their original purpose can indeed waste time. But on the other hand, mimesis and tacit knowledge are integral to how our species works. This argument is embodied in "Chesterton's Fence", which is also an argument for deeper understanding of past practices, but from the point of view that captures an evolutionary lens - what survived for so long might easily have served a purpose even if it has not been captured explicitly. Still, without frequent culling by forces like competition, strange, useless practices may indeed multiply and be perpetuated.

This also reminds me of the book In Gods We Trust: The Evolutionary Landscape of Religion which makes the argument that practices that are inexplicable are more likely to be handed down unchanged through time compared to that which is intelligible and thus open to continual reworking and change.

Chesterton’s Fence is the principle that one should not tear down a fence without knowing the purpose for which it was put up. In other words, one ought not to modify past practices without understanding their purpose.

One difference between the two principles is that Chesterton’s Fence generally refers to the question of retaining a practice that currently exists, while the goal of a cargo cult is to restore a practice that existed (or is perceived to have existed) in the past but does not currently exist.

Defense Spending

I discussed this before, but I think it is important to review two perspectives that indicate the magnitude of U.S. defense spending. While both are accurate (with caveats), both tell a very different story.

Such international comparisons are not straightforward. First, one must consider purchasing power parity adjustments; a dollar in Russia or China goes farther than a dollar in the United States, and so the disparity based on PPP would not be as great as the disparity based on the exchange rate, as is used in this plot. Second, Mackenzie Eaglen, a defense analyst at the American Enterprise Institute, argues that China is falsifying statistics, as they do with so many other topics, and that their true defense spending is greater than official numbers by a factor of 2.4. We will also see that calculating defense spending in the United States is not necessarily straightforward either.

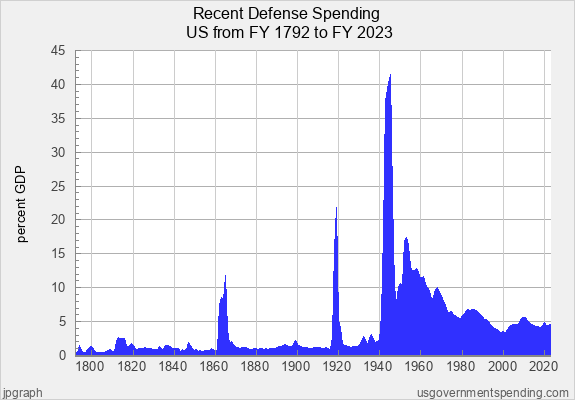

Looking at the U.S. defense budget, as a portion of GDP, over time tells a different story.

Taking the long view of U.S. military spending, one sees very clear spikes associated with the Civil War, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War, and lesser spikes associated with the War of 1812, the Spanish-American War, the Vietnam War, the Reagan-era arms buildup, and the post-September 11 arms buildup.

One observes the general pattern that, prior to World War II, the United States maintained minimal military spending, with spikes at times of war. With the onset of the Cold War, an to an extent persisting past the end of the Cold War, a permanently high level of baseline spending was set. These are the conditions that President Eisenhower discussed in his 1961 farewell address, in which he coined the term “military-industrial complex”. More about Eisenhower and military spending in a bit.

A third pattern is a general decline in military spending since the height around the Korean War, and this is the point that defense hawks seize upon. In 1979, a film simulating a Soviet nuclear attack against the United States called First Strike was released. The premise was alarming (a critic might say, alarmist), and the message that military spending needs to be increased was not meant to be subtle. That is exactly what happened in the 1980s. At no point since the end of the Cold War has U.S. military spending as a portion of GDP exceeded the value in 1979. Given rising federal debt and that population aging necessitates a larger portion of the federal budget to go to Social Security and medical care, I doubt that it ever will, absent a major war. The Peterson Foundation projects that spending as a portion of GDP will continue to decline through the 2020s.

As far as composition of the budget, we can look by activity and find the following changes from 1972 to 2022.

“Operation and Maintenance” covers military operations, training and planning, and non-VA healthcare. It is interesting to notice how that share has increased substantially over the period 1972-2022, despite the fact that in 1972, the U.S. was in the midst of the Vietnam War.

I don’t want to get too overloaded with statistics, so I’ll refer to this article on the FY2024 budget by service. The Army, the Navy and Marine Corps, and the Air Force and Space Force each have roughly equal shares of the budget, with the Navy and Marine Corps receiving slightly more.

Not all defense spending is contained in the Department of Defense, as this article helpfully explains. For Fiscal Year 2022, the DoD has $715 billion, the Department of Veterans Affairs had $113.1B, the Department of Homeland Security had $54.9B, the State Department had $63.6B, and within the Department of Justice, the FBI and Cybersecurity had $10.3B. Oddly, the cost of actual military operations is categorized under Overseas Contingency Operations, which is separate from baseline DoD spending; OCO was $69B in FY2021 and got as high as $186.9B during the surge in Iraq. Responsibility for nuclear weapons is split between the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy; the DoE’s share (mostly laboratory and other supporting work) was $16.3B in FY2021.

New Look

Combined, DoD and DoE spent $42.1B on nuclear weapons in FY 2021 and are expected to spend an average of $63.4B per year in the 2020s. This spending has been critically highlighted by several arms control advocates.

But the strategy of reliance on nuclear weapons was conceived as a cost saving measure under President Eisenhower’s New Look approach to defense spending. Recognizing that matching the Warsaw Pact with conventional forces for a possible war in Europe was not feasible, Eisenhower settled on the nuclear deterrent as a cheap and effective alternative. The Eisenhower administration rejected limitations on the use of nuclear weapons.

Another element of New Look was the use of covert actions, a much cheaper alternative to direct military intervention. Eisenhower authorized the CIA to assist the overthrow of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953, and the following year, the overthrow of Guatemalan President Arbenz Guzmán. Under Eisenhower, the CIA laid plans to depose Fidel Castro in Cuba, though those plans were not executed until the Kennedy administration’s disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion. I recommend the linked article as a good overview of Eisenhower’s foreign policy.

Since 1961, antiwar activists have seized upon Eisenhower’s use of the phrase “military-industrial complex” and his relative fiscal conservatism with regard to the military, without understanding the full implications of that approach.

Savings

The defense budget, as a major component of the federal budget at a time of concern over the debt, is one of the first areas for fiscal hawks to look at. How can this budget be reduced?

The obvious starting point is that the American military budget is so high because American military commitments are far more extensive than those of any other country, as outlined in President Biden’s Natural Security Strategy last year. Very large cuts to the defense budget are probably not possible without scaling back those commitments. That would be beyond what I can write about today. But let’s look at some other possibilities.

The military is notoriously a source of pork barrel spending, especially in the form of bases around the country. At the end of the Cold War, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process was instituted to close or repurpose bases that have outlived their usefulness. BRAC rounds have occurred in 1988, 1991, 1993, 1995, and 2005—no more than once every 10 years from 1988 to 2005—but have not occurred in the 18 years since 2005, nor is another BRAC round on the horizon. The 2014 National Defense Authorization Act explicitly prohibits the Pentagon from preparing for another round of closures, despite having been passed at a time of budget sequestration. These five BRAC rounds have saved an estimated $12 billion annually.

From Fiscal Year 1952 to FY2020, the number of active duty servicemembers has decreased 60%, but personnel costs have more than doubled. The end of conscription (which, to be clear, I don’t think can or should be reversed) means that the Pentagon has limited room to maneuver on personnel costs if they intend to meet recruiting targets, which all branches except the Space Force are missing. The Obama administration tried to rein in costs with, for instance, the Force of the Future strategy, but they made little headway. I expect that, due to demographic trends, the military, like all industries, will be forced to adapt through automation and efficiency.

The military’s usage of cost plus contracts is cited as a major inefficiency, and following great political pressure, the Obama administration and Congress made a move toward fixed price contracting, most notably with the Weapon Systems Acquisition Reform Act of 2009. However, fixed cost contracting has not been the panacea as hoped.

A report from the Heritage Foundation finds a number of ways the military could reduce costs without compromising (in their opinion) capability. If I did the math correctly, they report as much as $54 billion in annual savings, which is about 6% of defense spending, plus several recommended measures for which savings cannot be estimated. Most will be politically difficult (if they were easy, they would already be done), some of them merely shift costs to non-military line items, some of them may actually have an effect on capability, and there are some which, for other reasons, I doubt the wisdom. The Heritage figures include BRAC, measures of personnel costs, and contracting reforms, among other solutions.

I would feel comfortable estimating 10% as a ceiling on how much the military budget could be reduced without scaling back commitments or compromising on the ability to meet those commitments, taking into account realistic political constraints. I would be semi-confident in a ceiling of 5%.

Spending and the Defense Industry

I know that this post is long, but I do think the role of the defense industry has to be commented on.

The notion that the defense budget, and perhaps American foreign policy, is driven by the defense industry is a staple of the antiwar movement, illustrated (among many other places) here. This argument dates at least as far back as 1932, when Xavier De Hauteclocque wrote an essay entitled “Zaharoff, Merchant of Death”, which was expanded in a 1934 book Merchants of Death by Engelbrecht and Hanighen. In response, the Senate Munitions Committee, also known as the Nye Committee under chairman Gerald P. Nye, was created. The committee investigated whether armaments manufacturers unduly influenced American entry into World War I. The committee did not find hard evidence, but it nevertheless influenced the passage of neutrality legislation prior to American entry into World War II.

Since then, I am still not aware of any real evidence that the defense industry exercises undue influence on American foreign policy, despite the popular perception among the antiwar movement. This trope is a bit of a cop-out too; it substitutes an ad hominem attack for serious analysis of how to meet national security needs.

Conclusion

There is obviously a lot to say on this subject, and there is a lot more that I want to say but cut for reasons on length, and so this is a topic that I hope to revisit later on. But I hope that this has been a helpful overview of U.S. defense spending.

Quick Hits

James Pethokoukis wrote an interesting piece on solarpunk aesthetics and the shortcomings of the accompanying ideology, including a critical look at Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel, Ministry for the Future.

The US Megaprojects Database is attempt to crowdsource a comprehensive database of megaprojects in United States history. Feel free to contribute if you have ideas.

It recently came to light that SpaceX, which has been providing Starlink service to Ukraine, cut off that service to foil a Ukrainian attack on Russian warships in the Black Sea. Elon Musk’s explanation for episode, that for SpaceX to provide Starlink during the attack would risk precipitating a nuclear war, does not come strike me as plausible. The episode highlights a risk that too much dominance by SpaceX in the American aerospace industry could allow the company to assume the ability to conduct foreign policy from elected officials.

From 2019-2021, Russia’s military budget was 3-4% of GDP, and the war is expected to bring this figure above 10%.

Also in war news, the United Kingdom is the fifth country to declare the Wagner Group a terrorist organization. The United States has not taken this step, but there is legislation to do so. The Modern War Institute at West Point argues (not very convincingly in my view) that this step would be unwise.

There is an ongoing feud between Pope Francis and conservative U.S. Catholics, with the latest round being the pope accusing the latter group of placing political ideology ahead of faith. A year ago I noted the decline of Christianity in the United States and argued that politicization is a major factor explaining this.