December 9, 2023: Drone Delivery

Good evening. Drone delivery, or the idea of delivering parcels with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones), is an idea that has been a part of futurism for a while. There are no obvious technical barriers, and drone delivery would clearly be of great value. So where do things stand today?

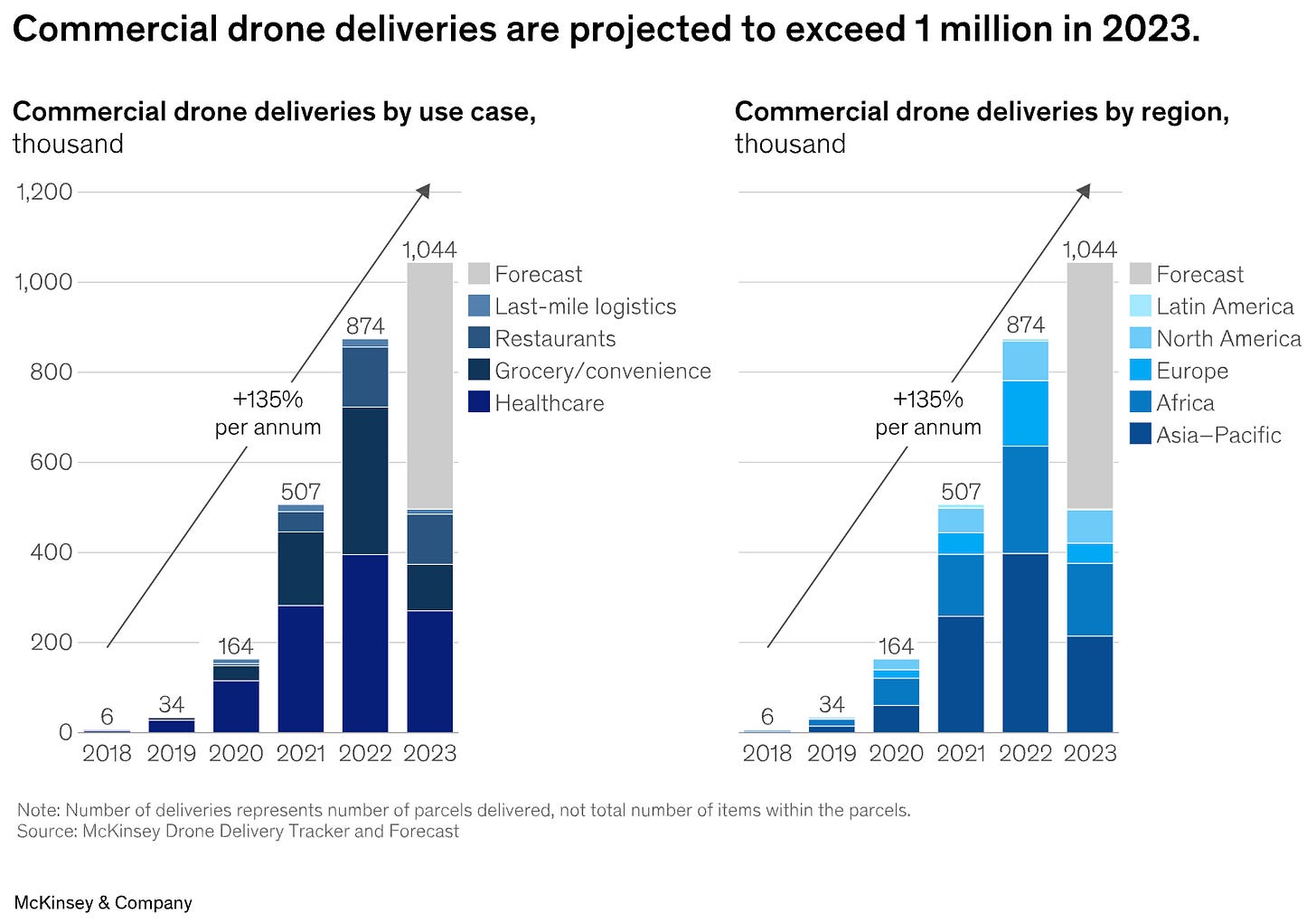

The technology is growing quite well.

This compares to 159 billion parcels delivered worldwide in 2021, so drone delivery constitutes less than 1/100,000 of the total. The idea is still very much, if you will pardon the pun, in the pilot phase.

One recent project is Swoop Aero’s trial for a medical drone distribution network in Ethiopia. The trial has been regarded as successful and is planned to expand next year. This project is an ideal proving ground. Vaccines need to be refrigerated, and thus the speed of delivery is critical. The project serves areas that are not well-served by roads. Vaccines are small and have a high value-to-weight ratio.

Also for medical distribution is Amazon’s trial project in College Station, Texas, which delivers prescription medications to customers in the area. Chick-fil-A is also trialing drone delivery at a location in Brandon, Florida. These three things are just a sample of recent projects.

The advantages of drone delivery are numerous, and we will start with the obvious advantage: cost. In 2020, Gartner estimated that drone delivery would have a 70% lower operational cost than van delivery. An article from a few years ago estimates that the operational cost for drone delivery is €1.59/parcel, compared with €4.59/parcel for vans. In dollars, that would suggest a total savings potential of $458 billion annually worldwide, though the actual amount would be less, given practical limitations of drones. Along with lower cost is faster delivery times. On the minus side, drones have a higher capital cost than e-bikes, which is a major competing solution for a low-ecological-impact delivery method.

Speaking of which, a paper last year finds that delivery drones, compared to diesel delivery trucks, save 94% energy consumption and 85% greenhouse gas emissions. On both metrics, drones perform significantly better than electric delivery trucks as well, though e-bikes perform even better than drones. Over 159 billion packages, the energy savings is 1.6 exajoules, or about 0.25% of world primary energy consumption, and the greenhouse gas savings is 59 million tons of CO2, or about 0.15% of world total. Again, these are overestimates because not all parcels are suitable for drone delivery, nor is a diesel truck necessarily the counterfactual in all cases, but I present them for illustrative purposes.

(The model in this paper estimates that 41% of parcels are suitable for drone delivery, taking several constraints into account. On the other hand, the volume of e-commerce is growing rapidly. The Pitney Bowes analysis that estimates 159 billion parcels delivered worldwide in 2021 forecasts this number to be 205 billion in 2024, and we should expect continued growth from there.)

Road space is another major advantage to drone delivery. Urban freight transport is estimated to comprise 7% of the traffic on the roads but generate 28% of the congestion. Another study finds that congestions from truck traffic causes a loss of $28 billion. It’s not clear to me what share of this traffic could be replaced by drones, but we are looking at billions of dollars worth of congestion costs relieved. Traffic congestion is, in my analysis, the most potential bottleneck to urban density, and those with experience at planning commissions will recognize congestion as a leading objection to new development. Drone delivery is a solution for building compact cities with a high quality of life.

All emerging technologies face growing pains, and drone delivery is no exception. Residents in areas with drone delivery trials complain about noise; the passage of a delivery drone generates noise that is comparable to a leaf blower or a lawn mower. The very word, drone, has an alternate meaning of a monotonous, annoying buzz. There are ongoing efforts to develop quieter drones.

Safety worries revolved around the “last meter” problem, which is the final separation of the package to its destination. The drone could drop its package, hurting someone on the ground of damaging the package itself, or have a collision in the drop-off process. A drone could crash due to mechanical failure or other causes. There are also cybersecurity risks.

There are privacy objections as well, and also objections about the visual obtrusiveness of drones. There are non-issues too, such as worries about unemployment as drones are more efficient than delivery vans; see my post on technological unemployment for more discussion.

These issues are very real, but I don’t see any show-stopping concerns. Problems around noise and visual pollution, security, and privacy are best resolved through the experience gained from small-scale trials, which is exactly what is happening now. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration has set a line-of-sight rule for all drone operation, including delivery drones, that requires that the device remain within the line of sight of a human operator. The FAA then grants waivers on a limited basis. This policy is, in the judgment of the Center for Data Innovation, overly restrictive.

Finally, the rebound effect must be commented on. In energy economics, the rebound effect is the well-known observation that when an innovation enhancing energy efficiency occurs, either more of the more efficient good will be consumed, or some of the energy savings will then be spent elsewhere in the economy. We should expect that parcel delivery will continue to grow no matter what, but we can also expect that if drone delivery becomes widespread, the growth will be greater than it would be in the counterfactual, though I cannot hazard a guess as to what the magnitude of this effect might be.

The rebound effect is a good thing. It means that people can order more things they want. The rebound effect is only be a bad thing if the more-efficient activity has so much negative externality that the increase in negative externality outweighs the increase in consumer surplus. The best solution is to eliminate negative externalities by internalizing them, such as with carbon pricing, and where this is not feasible, a secondary solution is to regulate where necessary, such as perhaps noise ordinances on drones. Trying to kill an efficient activity with regulation is not a reasonable solution to the rebound effect.

Drone delivery should be recognized as one of many solutions for last-mile logistics. E-bikes, as noted above, have many advantages too. There are ground-based delivery robots. There are micro-hubs for customers to pick up packages in a central location. Logistics are a central, perhaps the central, problem in urbanism. The whole point of a city is the agglomeration economy that comes with the reduced transportation costs of proximity. Thus the efficient transportation of goods and people is the core issue.

Quick Hits

There is a long-standing border dispute between Venezuela and Guyana over the Essequibo region, which is internationally recognized to be part of Guyana. Last weekend, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro pushed through a referendum on whether the territory should be considered part of Venezuela, which raises the specter of armed conflict. The recent discovery of oil in the region is a major reason the issue has come back to the forefront of attention. Most international media has recognized this action as an unwarranted land grab by Venezuela. As the United States Congress debates a further round of funding with regard to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan, the dispute is yet another reminder of the extent of aggression in the world.

“Company Man” is another YouTube channel that I have started watching and enjoying. His videos are about companies, mainly well-known consumer brands, and why they have achieved good or bad times in the market. I found his analysis of JCPenney particularly interesting. While JCPenney still exists, it has clearly fallen on hard times lately. The main problem, according to his analysis, is that Ron Johnson, previously an executive with Apple, tried to make Apple Store-like changes to JCPenney that simply didn’t work. This is a good example of what I previously described as cargo cult-thinking.

Brian Potter of Construction Physics considers why ADUs (accessory dwelling units) are more expensive to build in California than it appears they “should” be, considering that California has adopted the HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development) Code in an attempt to streamline construction. He doesn’t have a definitive answer to this question. It looks to me that, in the absence of market clearing, construction costs are a kind of negotiation between what the inherent cost is and what the property owner is willing to pay, and so we might ask what additional barriers to ADUs still exist.

Maxwell Tabarrok suggests that the overall burden associated with NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act that is often seen as a barrier to building things, peaked in 2016. The FAST Act, legislation in 2015 to streamline approvals, is suggested as a possible cause of this, but it is not clear.