Thoughts for July 31, 2022

Good afternoon. A long post today, which topics of the Inflation Reduction Act, James Lovelock, The Line, right-wing Solarpunk, South Korea birth rates, Pleistocene societies, and Serbia and Kosovo.

Inflation Reduction Act

The news this week was dominated by an unexpected breakthrough negotiation between Chuck Schumer and Joe Manchin, leading to Manchin’s support of the Inflation Reduction Act, a stripped down reincarnation of the Build Back Better Act which he opposed. Passage of the IRA is not a sure thing; one of the major stumbling blocks will be whether Kyrsten Sinema supports it. All Republicans will presumably oppose it, so all 50 Senate Democrats must support it for the bill to pass. I won’t try to be comprehensive, but I’ll share a few notes.

The title, Inflation Reduction Act, apparently comes from a recognition that federal deficit spending is a driver of inflation, and the bill seeks to reduce the deficit. This high-level budget impact overview shows that the bill will raise $739 billion in revenue, spend $369B on climate policies, $64B on an Affordable Care Act extension, and leave the remaining $306B for deficit reduction. The revenue will come from a 15% minimum corporate tax ($313B), prescription drug pricing reform ($288B), enhanced IRS enforcement ($124B), and addressing carried interest ($14B). An analysis on the distributional impacts finds that people earning <$10K/year will be hit hardest, I presume because of the pass-through effects of corporate taxes, but I don’t know the details.

Despite being scaled back from what the BBB envisioned, the IRA’s climate provisions are still a major climate policy. The always-good Sonal Patel runs through major provisions. It makes a fairly wide set of investments, in the form of tax breaks and direct spending, in various clean energy tools, including electric vehicles, wind and solar power, hydrogen, nuclear power, carbon capture, biofuels, heat pumps, and critical minerals. There are also some provisions on environmental justice, agricultural emissions, and tree planting. See also this overview of the climate provisions. This overview from Vox is less helpful but still provides some useful details.

The reaction from the environmental and climate communities has been mostly positive, though some such as the Center for Biological Diversity object to provisions that would ease oil and gas leasing on public lands. Citizens Climate Lobby, which has focused on getting a carbon fee and dividend through Congress, is pleased in particular with the methane pricing provision. There is also some noise about housing spending and zoning reform, or lack thereof, in the IRA. The BBB had some very modest federal efforts toward zoning reform which are entirely absent in the IRA.

The Rhodium Group has some analysis of the emissions reductions that can be expected. Much of the press coverage states that the IRA will lead to a 40% emissions reduction by 2030. Such statements are misleading because much of the reduction is expected in the absence of the bill. But the IRA is expected to lead to meaningful reductions. In not-yet-published analysis, Jesse Jenkins states that the IRA will induce 5 billion tons of reductions over a 10 year window, the same as the 10 year budget window for the $369B figure above. That works out to $74/ton for emissions reductions. On the expensive side, but not outrageously high.

In his statement about the IRA, Manchin expressed support for permitting reform. I don’t see a whole lot of that in the bill itself, so maybe he’s looking ahead to future legislation? I’d appreciate it if someone in the know enlightened me on this.

My sense is that the climate provisions seem mostly good, and I like the comprehensive approach. But there is a clearly protectionist tinge which surely raises the cost. I would also have liked to see more emphasis on regulatory reform. Here’s the full 725 page bill if you have nothing else to do.

James Lovelock

James Lovelock was a polymathic scientist who is best known for developing the (controversial) Gaia Hypothesis, which holds that living organisms keep Earth in a state of homeostasis. Lovelock died this week at the age of 103.

Using an electron capture detector he invented, Lovelock discovered a presence of CFCs in the atmosphere. However, he didn’t realize at the time that CFCs would release chlorine and threaten the ozone layer.

Lovelock was a strong proponent of nuclear power. He discussed the natural fission reactor at Oklo, in Gabon, and regarded fission as perfectly natural and compatible with life. He regarded climate change as a serious threat which calls for serious solutions, and nuclear power was chief among them. Among Lovelock’s more worrisome views about the climate were that democracy would have to be curtailed and that 80% of the human population would die from global warming in the 21st century, but he later came to regard his earlier views as too alarmist. Lovelock also endorsed the controversial idea of fertilizing the upper layers of the ocean to absorb CO2.

Lovelock’s last book, published when he was 100, is entitled Novacene. He argues that superintelligent machines, which are on the verge of being developed, will be crucial in restoring Earth’s ecological balance. The advent of such machines may also be the beginning of the process of seeding the cosmos with life.

Many people of my generation were introduced to the Gaia Hypothesis, and Lovelock’s Daisyworld simulation to test it, from the computer game SimEarth.

Lovelock wasn’t right about everything of course, but he was a fearless and versatile thinker who showed capacity to evolve his ideas. It’s a trajectory that reminds me of Stewart Brand or the late Freeman Dyson. He is an excellent role model for young scientists today.

The Line

The Line is a newly announced urban development project from Saudi Arabia, part their $500 billion NEOM ambition. It is a 170 kilometer proposed linear city, and it will be 200 meters wide and 500 meters tall (by comparison, One World Trade Center in New York City is 541 meters tall, including the spire). There will be no cars. Day-to-day amenities will be available within walking distance; this, together with the city’s height, will allow very high population density. Travel from one end to the other will be achieved by train, and it will take 20 minutes to travel across. That would be faster than the Shinkansen in Japan and comparable to the fastest maglev trains.

Now, I’m going to root for almost any urban design project to succeed, including this one, but most ambitious, greenfield projects either fail outright or perform well below expectations. And The Line carries some obvious problems.

First of course is cost. I have no idea how much it would cost to build such a structure. Al Jazeera estimates $1 trillion for a structure that would house 5 million people, for $200,000 per person. Sounds OK but too low. Taller buildings cost more per square foot than shorter buildings. It’s that, rather than hard technical constraints, that limit the size of skyscrapers and why 500+ meter buildings are very rare. For some back of the envelop calculations, One World Trade Center cost $3.9 billion (about $4.8B adjusted for inflation) and has 3.1 million square feet of office space. New York City offers 5.4 billion square feet of building space for 8.4 million people. If The Line is to provide the per-capita living space of New York City at the costs of One World Trade Center, the cost would be around $5 trillion, not $1T, which is a million dollars per person. I have a hard time imagining how that could pencil out.

Let’s talk about the shape. One of the first things you learn in urban economics is the standard urban model, which holds that under idealized circumstances, cities will develop as circles. The central business district, which is the densest part, is at the center, and density tapers off until one reaches the edge of the city, where agricultural use is of higher value than urban use. Circles are the most efficient shape for bringing the largest number of people together with the shortest transportation distances. Lines are the least efficient shape.

Greenfield cities are not impossible—all cities were greenfield cities once—but they are at a disadvantage compared to expansion of existing cities. That’s because a greenfield city is hard to get started. You need to attract a first wave of citizens and a first wave of employers, and each will be hard to attract without the other. Often the needed anchor comes in the form of public administration, as was the case in planned capitals such as Washington, D.C., Brasilia, and St. Petersburg. What will be the anchor at The Line? Meanwhile, The Line is to have a construction period of 50 years, and Saudi Arabia’s total fertility rate is crashing and now barely above replacement level. It is hard to imagine strong demand for urban real estate persisting into the late 21st century.

In conclusion, I appreciate the pretty pictures, but it is likely that this project will fail outright, or at best fall far short of expectations.

Solarpunk for the Right

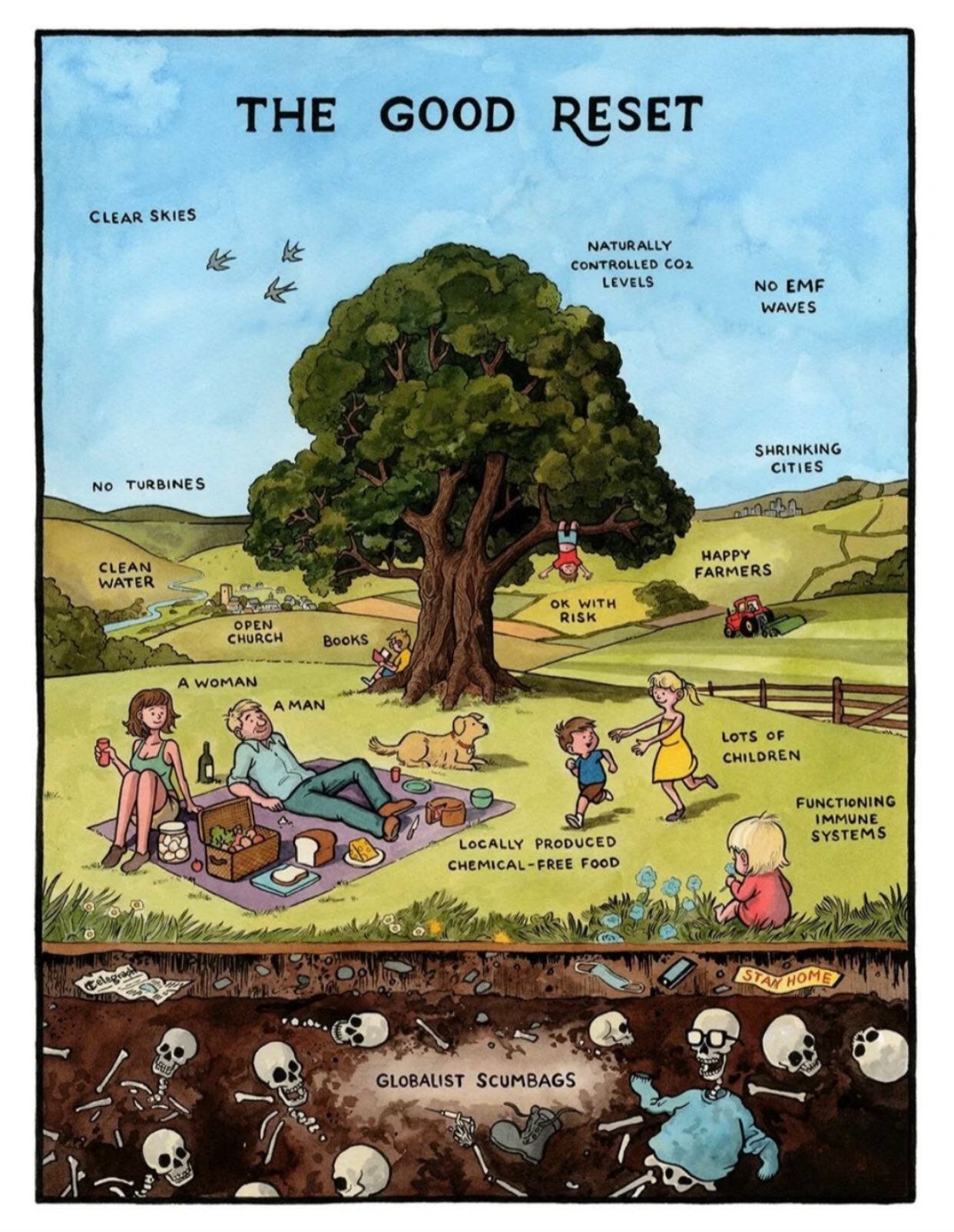

I’m not sure what we would call it, but here’s a picture that came to my attention this week.

The title, “The Good Reset”, is obviously a play on conspiracy theories around “The Great Reset”, and the image plays on a number of conspiratorial hobbyhorses of the populist right. But for better or worse, it presents a definitive eco-utopian vision, parallel and quite similar to Solarpunk aesthetics. Both are rooted in opposition to central authority, craving for decentralization, and glorification of nature. Both share more in common with each other, and with their forebearers in the Romanticism, than either do with, say, ecomodernism. The fact that one is associated with the political left and the other the right is a minor detail.

There is no need to critique everything in this picture, but one should simply ask if it is plausible, let alone desirable. Without fossil fuels (“naturally controlled CO2 levels”), wind turbines, or EMF sources, one wonders where the energy will come from to support a growing (“lots of children”) population. There presumably isn’t much international trade (“locally produced chemical-free food” and “globalist scumbags” in the ground), and there are “shrinking cities”, so how does the economy function? Presumably it is a wealthy, high tech economy if it is to support “lots of children”, and I know of no model for such an economy that doesn’t involve an advanced division of labor enabled by trade and cities.

By the 21st century, I hope most of us have learned our lesson about utopian ideas.

South Korea Birth Rates

South Korea has the lowest birth rate in the world, with a total fertility rate of 0.81, less than half of the ~2.1 needed to maintain a stable population. The value is so low as to threaten the long-term viability of the nation. This video by Sienna Hong discusses the reasons. The video is good, interweaving statistics with her personal experience in Korea.

First, Hong notes that marriages rates are also low. Married couples don’t have exceptionally few children in South Korea compared to other countries. So low marriage rates and low birth rates should be understood together. She discusses several common explanations: high housing costs induced by high concentration in Seoul; high education costs; the desire to put personal life ahead of family life and the related fear of the family/career tradeoff; job discrimination around maternity leave and against married women; and an intense work culture.

I haven’t written as much about birth rates lately, mainly because I got tired of discussing a problem without proposing solutions. But I continue to think about it. One model that unifies most of the explanations in this video is Peter Turchin’s model of elite overproduction, about which I have written before. Under this model, we would expect to see geographic concentration—a particularly severe problem in South Korea—parenting competition in the form of high education spending, and employers who feel empowered to discriminate and demand long hours.

Complex Societies in the Pleistocene

There is a common stereotype of late Pleistocene (~129-11.7 thousand years ago) societies that they were small—only as many individuals who could mutually know each other well—nomadic, and egalitarian. Academia is moving beyond this view, though it remains in academia and is pervasive beyond. In particular, contemporary notions of evolutionary psychology are informed by the “nomadic-egalitarian” model.

Such is the argument of this new paper by Singh and Glowacki. They argue that the nomadic-egalitarian model is outdated and should be replaced by a diverse histories model, which holds that in addition to the small, nodamic, egalitarian societies we associated with the Pleistocene, there were also larger, less mobile, and more hierarchical societies.

The authors note that much of our understanding of pre-Holocene societies is informed by contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, and that there are severe problems with extrapolating from the latter to the former, since proximity with agrarian societies would have changed the hunter-gatherer societies. They document how consumption of seafood and fishing settlements was both earlier and more extensive than previously imagined. While there was no agriculture in the sense we know it now, there were deliberate efforts to cultivate plants such as by fire, which would have required relatively stationary societies.

I noted earlier that research is showing that large-scale cooperation was much more widespread in the Pleistocene than previously imagined. And I also noted, then and now, that our evolving understanding of the Paleolithic past should prompt a rethink in evolutionary psychology especially. Singh and Glowacki document large-scale, hierarchical societies back to the start of the late Pleistocene (~129 kya) and possibly earlier. Thus such societies existed alongside the development of the modern human mind, which may have evolved 70-164 kya. The idea that a nomadic, egalitarian tribe based entirely on personal knowledge is the “natural” state of humans should thus be discarded.

It is exciting to think of how many prehistoric societies there were that demonstrated enough complexity to deserve being called civilizations. Compared to such civilizations, the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza was recent.

Kosovo and Serbia

Today there was a skirmish between Kosovo and northern Kosovo Serbs over regulations on license plates. Hopefully and most likely the affair will pass without major problems, but the status of Kosovo, and that of Serbs in north Kosovo in particular, is a dangerous flashpoint for conflict. Kosovo declared independence from Serbia in 2008. Their status as an independent nation is recognized by the United States and most of Western Europe, but not by Serbia, Russia, or China. There are fears that Serbia, with Russian backing, could launch an invasion of Kosovo. Stalling in their efforts to gain full international recognition for independence, Kosovo is also considering a union with Albania, though this would have its own challenges.

There is a helpful explainer from last year by Caspian Report. The channel as a whole has good analysis of world geopolitics, and I recommend it.