Thoughts for December 4, 2022

Good afternoon. Today’s topics are human space flight, whaling, and sperm counts.

Human Space Flight

Many spaceflight enthusiasts approach the question of spacefaring from an envisioned distant endpoint. A spacefaring civilization will, it is hoped, support a far larger population, at a far higher standard of living, with far greater scientific and technical knowledge, and with far greater freedom than a perpetually earthbound civilization could support. Furthermore, such a civilization, it is hoped, could function with minimal environmental impact on biotic ecosystems and would be more resilient against catastrophic events.

But there is the major challenge of how we reach that point. Last week I took a stab at that question, arguing that a spacefaring economy will be an extension of the present global economy, and it will not develop independently of the larger economy. I left an out: “It is a broad and somewhat vague definition by design, as how, or even whether, the process will unfold is hard to predict.”

The work of space migration will be conducted by entities that, even if motivated by a grand, multicentury vision of a spacefaring civilization, must be focused on near-term business objectives or political considerations. Historically, progress is driven by near-term considerations, with the macrotrends of industrialization, economic growth, advancing technology, and rising standards of living emergent properties of those considerations. I cannot readily think of an example where a macrotrend has been the primary motivation of a successful engine of progress. And so space advocates are left to put the cart before the horse: presenting a plausible business or political case that will move us closer to the vision.

This leads to some casting about. Space tourism, discussed in my post last week, has been a major hope as a kickstarter for space migration since Dennis Tito’s trip to the International Space Station in 2001. After Tito’s and several more trips to the ISS in the 2000s, space tourism mostly halted in the 2010s, with again a few successes in the 2020s, such as Inspiration4 and Blue Origin’s New Shephard launches. See also this review of space tourism ventures that have come and gone without producing success. It remains unclear whether space tourism is a viable driver for more widespread spacefaring activity. Hope is also placed in SpaceX’s plans to settle Mars, but the plans remain a black box.

The case for the broader space industry is indisputable. Satellites for Earth observation, communication, and ballistic missile detection and possible interception, as well as interplanetary probes and scientific instruments such as the James Webb Space Telescope, are now widespread, and this industry is expanding with a solid business case. But it is unclear how this translates into a case for human space flight and a pathway to space migration.

Compounding the problem is that much of the opposition to human space flight is from an environmentalist perspective and is, upon cursory examination, severely misguided. First, the impacts of human space flight today and in the foreseeable future—which are mainly ozone depletion, black carbon emissions in the stratosphere, and greenhouse gas emissions from energy—are so minuscule in comparison to other activities that it is clear that the opposition, like that against plastic straws or cryptocurrency mining, is driven by a desire to pick a culture war rather than by any serious environmental concern.

The tired refrain, “why are you focused on space when there are problems on Earth?” could just as well be asked to critics of human space flight as advocates. Some such comments, such as those of Prince William, when paired with the same’s remarks on population control, suggest that misanthropic motivations may be at work as well. The grand vision of a flourishing human civilization spreading through the solar system and the galaxy is a positive view of humanity, and it is fundamentally at odds with views that human flourishing is a negative thing that needs to be restrained.

But while opposition to human space flight can be dismissed as curmudgeonly antihumanism, doing so does not obviate the need to be rigorous in developing a pathway to space migration. It frustrates me how little rigor there is on the subject.

Whaling

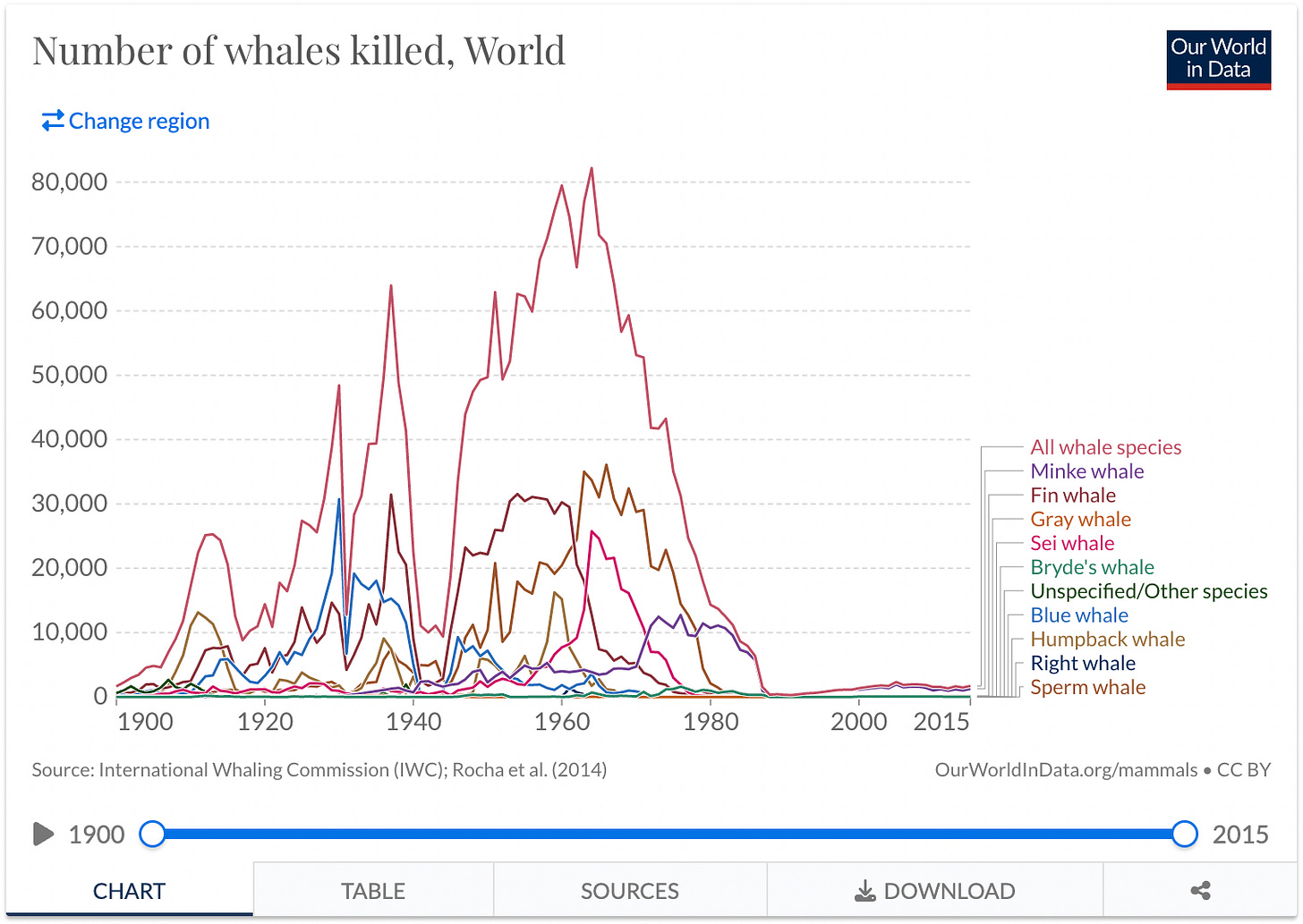

The trends in whaling mark a major environmental success, though one that is still incomplete. It also illustrates several broader environmental principles.

Commercial whaling has mostly disappeared today compared to the peak in the 1960s.

Whaling has occurred since Neolithic times, and it greatly expanded in the Middle Ages. Whaling was an important industry in the colonial America and the United States, with products including whale oil and spermaceti for lighting, baleen for fashion, and ambergris for perfumes. These products have disappeared, and today whaling occurs primarily for meat.

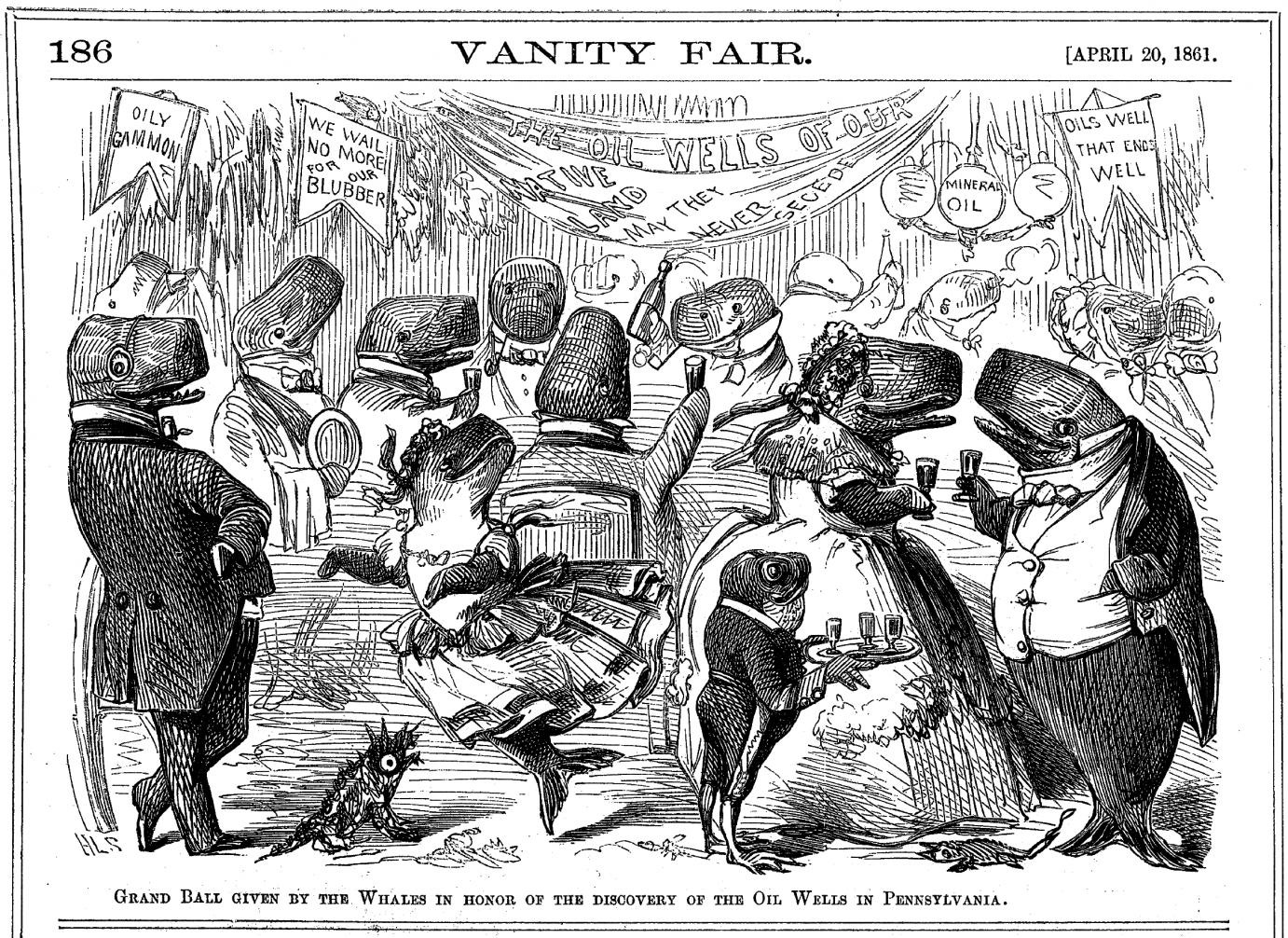

The above image depicts a celebration by whales of the discovery of petroleum drilling, an alternative to whale oil. Terrestrial alternatives for baleen and ambergris would follow. But the celebration was premature; in 1853, at the height of profitability, the American whaling industry, which was the largest in the world at the time, killed 8000 whales, a tenth of the world total at the peak year in 1964.

Due to concerns about falling whale populations, the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling was established in 1946, which established the International Whaling Commission. In 1982, the IWC banned commercial whaling, a ban which took effect in 1986, though the ban had some exceptions for scientific research and subsistence hunting. Since 1986, Japan, under the heading of scientific research, has been the top whaling nation, followed by Iceland and Norway. In 2018, the Florianópolis Declaration ended the scientific research exception for hunting, prompting Japan to withdraw from the IWC.

Anti-whaling advocates look to whale watching, an industry they hope will create more economic value for whales alive than hunted. Advocates also hope that whale watching will foster greater concern for whales among the public. While the IWC’s position of whaling is motivated (ostensibly but controversially) by conservation, anti-whaling campaigners also invoke cruelty concerns. Beyond legal strategies, anti-whaling campaigns take the form of direct action, which in many cases amounts to ecotage and violence.

What can we learn from all this that is applicable to other environmental issues? First, economic alternatives to an environmental ill are a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition to remedying that ill. The peak of worldwide whaling came far after petroleum drilling, electric lighting, chemical alternatives to baleen and ambergris, and hoop skirts going out of style. The story of stratospheric ozone, where discovery of the ozone hole, development of low ozone-depletion refrigerants, and the Montreal Protocol came in rapid succession, can be a misleading template for how environmental issues unfold.

Second, too harsh of a legal regime can generate blowback, as was the case of Japan’s 2018 withdrawal from the IWC. Environmental activists may dislike compromise when deeply held moral convictions are at stake, but compromise is necessary to get things done.

Third, there seems to a disconnect between anthropocentric and eco/biocentric motivations behind environmental policy. Conservation, which itself straddles the three worlds, was the main factor behind the drop in whaling in the late 20th century. Whale watching is clearly an anthropocentric consideration, while the biocentric motives behind anti-whaling campaigns have been mostly sidelined. Although I have my skepticism about invoking anthropocentric arguments behind environmental values that are held for different reasons, I don’t know if there is a clear alternative.

Sperm Count

Over the last few decades, several studies have demonstrated a significant reduction in human male sperm count. Especially prominent is a 2017 metastudy by Levine et al. Reviewing past sperm count studies, Levine et al. find a 59.3% decline in sperm count worldwide from 1973-2011. A trio of related studies in 2017/18 found major declines in Europe, in Africa, and in Asia. Although this subject have been controversial, Levine et al. has proven to be more convincing to experts in the field than past work.

Not everyone is convinced, though, at least not the authors of this 2021 study. This study, however, seems to dispute the significance of the metric and the political implications of Levine et al. more than it disputes the basic conclusions.

Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that, while there is some evidence of rising male infertility, the degree of the rise is nowhere near as drastic as the numbers might lead one to believe. As best as I can tell, the decline in birth rates around most of the world in the last few decades is caused mainly by cultural and economic factors, not by infertility.

The cause of falling sperm count is unclear, though plenty of speculation has been made. Alleged causes include unhealthy diets, pesticides, microplastics, and endocrine disruptors such as BPA and DDT. I would consider these hypotheses interesting but unproven.

Children of Men is a good movie, but I don’t see grounds for panic that a similar type of mass infertility scenario is in the cards. Nevertheless, with good evidence for dropping sperm counts, no sign that the downward trend is ending, and the cause for the decline unclear, there is cause for concern. But there is more cause for concern about whether modern societies are, from a cultural and economic perspective, conducive for families.