Last month, the Energy Institute released the annual Statistical Review of World Energy, but only now am I writing about it. The Statistical Review was published from its inception in 1952 to 2022 by British Petroleum, and for the last two years it has been housed by the Energy Institute. Thus the Statistical Review is an institution in itself, older than the International Energy Agency and the U.S. Department of Energy, both of which have their origins in the 1973 oil crisis. The Statistical Review offers concise, high level energy statistics, and its annual June release is an event that people such as myself who work in energy policy look forward to every year.

Much has been said, including by me, about an energy transition, which generally means a transition of the world energy system to a system without net carbon dioxide emissions. Today (well, recently enough that the picture has not changed substantially), more than 70% of greenhouse gas emissions, of which CO2 is the most significant, come from energy combustion. But as we will see, evidence for the energy transition, at least on a time frame that most of us would consider to be acceptable, is not there.

The Big Picture

World energy consumption by major fuel source is as follows.

The most obvious point is that oil and coal are at record highs. Gas is near the record high set in 2021. Hydropower has shown slow but steady growth, at least until 2020. Nuclear power has been struggling for decades, despite the so-called nuclear renaissance of the 2000s. The growth of wind and solar has been impressive, though they would look more impressive if we didn’t plot them on the same scale as everything else. Other forms of renewable energy—I wrote about geothermal and ocean energy in April—are struggling to gain traction.

Greenhouse gas emissions from energy set a new record in 2023, exceeding 35 billion tons per year for the first time, and a full 1.6% higher than the previous record set in 2022.

Natural gas is controversial, but viewed mostly negatively, among environmentalists despite producing half the emissions per kilowatt-hour as coal and relatively little of other air pollutants. For this reason, natural gas is sometimes called a bridge fuel, meaning that while a coal-to-gas transition is a win for emissions reductions, it is inadequate in and of itself. PAGE, a natural gas advocacy organization, points out that a coal-to-gas switch has been the most important driver of emissions reductions in the United States in recent years, but it should be kept in mind that the hydraulic fracturing revolution, which has greatly increased low-priced gas on the American market, has not been replicated worldwide.

To keep things very simple, I plotted the share of primary energy from fossil fuels.

It is not obvious due to zero-scaling, but the fossil share went up in the late 1990s and early to mid 2000s. During this time, the struggles of nuclear power were very apparent, while wind and solar had yet to grow enough to put a big dent in the fossil share. Environmentalist opposition to nuclear power is one of the most destructive errors in the history of the movement, though as I wrote about last year based on Jack Devanney’s work, environmentalist opposition is the least of the industry’s problems.

At the rate we’re going, the share of energy from fossil fuels will reach zero in the year 2420. Hopes for a faster transition rest heavily on learning curves, the idea that as more wind and solar energy are deployed, the cost of these technologies will fall, thus stimulating further deployment. We should end up with a growth curve for wind and solar that looks as exponential as we have seen in the past, so that these technologies will become the dominant energy sources in a few decades. I am working on a large project on learning curves now and will have more to say about them later, but for now, if one really believes that climate changes poses an existential threat to civilization, then pinning hope for a solution on learning curves is an extraordinarily reckless move.

Substitution or Augmentation?

I’ll come back to learning curves in a bit, but now I want to turn to another question: are low(er) carbon energy sources actually replacing high carbon sources, or are low-carbon sources simply augmenting the energy supply? Renewable energy subsidies are based on the expectation that renewables will displace fossil fuels, and therefore renewables have an external benefit that merits a subsidy. The following is an attempt to answer that question. The graph is a bit confusing, so I’ll explain.

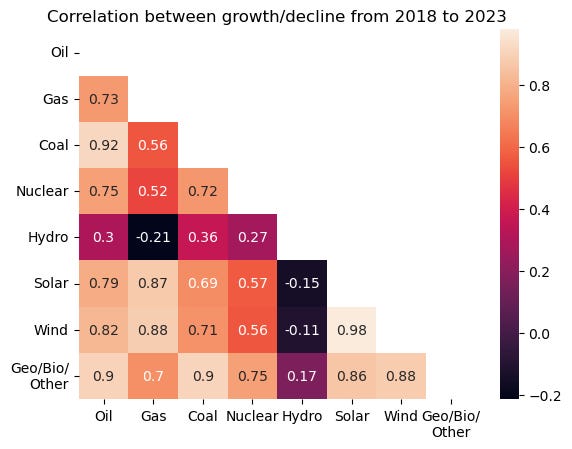

A value of 1.0 would be a perfect, lock-step correlation. Wind and solar have a remarkably high correlation, which shouldn’t be too surprising. What is more surprising is that, with the exception of hydropower, any two energy sources show correlation at least 0.5. Nuclear shows a relatively weak correlation with gas, wind, and solar, which might explain some of the nasty politics between advocates of these sources. But overall, it is clear that energy sources are generally complementary, not substitutes, and so subsidizing one probably does very little to replace another. I think what is going on with hydropower is that, while hydro overall is stagnating, the year to year differences are highly dependent on weather, and so this turns the correlation into noise.

This is a quick and dirty calculation, which can be seen in a Jupyter notebook here. I encourage the interested reader to experiment with different time frames or different growth metrics, and the apparent result might vary.

An analysis by Richard York agrees; he finds that when alternative (i.e. non-fossil) energy sources are deployed, more than 75% of the new energy is added to the supply or displaces other low-carbon energy, and less than 25% displaces fossil fuels. With electricity, less than 10% of low-carbon energy displaces fossil fuels. Little and Sardosky find a more generous 18% supply rebound, rather than 75%+. Another paper finds that natural gas generally does not replace coal in the electric grid. This appears to be a common pattern, and it is highly analogous to the rebound effect for energy efficiency.

Let us also consider the historical perspective. The Industrial Revolution can be told as the replacement of traditional biomass energy with coal, then oil, then natural gas. But that’s not exactly what happened. In the year 1800, biomass constituted 98% of the world’s primary energy supply. In 2000, that value was 10%. But in absolute terms, biomass consumption peaked in 2000 at over twice the 1800 value, at it is still (as of 2022) nearly twice the 1800 value. Imagine, if you will, the year 2224 in which energy consumption is 20 times the current level, dominated by fusion and/or space-based solar, and yet fossil fuel consumption is twice the present level.

The bottom line is that there is little evidence that new energy supply displaces some undesired old supply, and the fact that decades of energy policy has been predicated on the assumption that it does is ludicrous.

Electrification

One more item based on the Statistical Review. Electrification is one of the key pillars of most energy transition scenarios, by which it is meant that that most energy is derived, directly or indirectly, from electricity. This means, for instance, electric vehicles, electrolyzed synthetic fuels, electrolyzed hydrogen as a reducing agent for steel production, and so on.

As shown in the Statistical Review, electrification is proceeding, but not at at pace that is acceptable to most clean energy advocates.

I wouldn’t take the apparent slowdown around 2000 too seriously. The Energy Institute offers a constant primary energy factor up through 2000, followed by a gradually increasing PEF. If a constant PEF is used for the whole time series, then the slowdown disappears, and the entire plot looks linear. Using the EI’s PEFs and extrapolating the 1985-2023 trend, we should see a 100% electricity world energy system around the year 2239.

Once again, hopes for faster electrification rest on learning curves. This paper extrapolates learning curves for electric vehicles, heat pumps, low-carbon electricity production, and various other technologies and estimates that 66% of the world’s final energy demand should be from electricity by midcentury. I figure this translates to around 80% of primary energy. We are on track to get to 80% by around 2164. To get there by 2050 instead, electrification would have to accelerate by more than a factor of 5.

Once again, I don’t find this result to be plausible, and it is grossly irresponsible to pin so much hope about the energy transition on wild extrapolations of learning rates.

Conclusions

The need for rapid decarbonization of the energy system has been stated so many times that it is a cliché, and yet by all appearances, we are still in the parking lot. “Oh, but you wait and see, the Inflation Reduction Act will be the catalyst that finally puts the transition into the fast lane”. Maybe so, but I have been working professionally in energy policy, and before that following as a hobby, for a long time now. During that time, I have seen similar claims about the Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022), COVID-19 (2020), the Paris Agreement (2015), the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009), Al Gore’s movie An Inconvenient Truth (2006), September 11 (2001), and the Kyoto Protocol (1997). I have no qualms about saying that I’ll believe it when I see it, especially when the same mistakes are being made with the IRA as in the past.

There are many important ideas out there, like using technology-neutral clean energy standards rather than renewable energy standards, or various reforms to the permitting of solar, wind, and high voltage transmission. But we need to be clear-eyed about the scope of the problem. Supply rebound is real, and learning curves are not magic. I see only the following possibilities.

Option 1: some sort of international carbon pricing on the order of at least $50 per ton of carbon dioxide. My favored policy for doing so is a carbon fee and dividend, but there are many plausible pathways to putting a price on carbon.

Option 2: come to peace with a warmer world.

Option 3: there is no option 3.

Perhaps Option 2 merits further reflection. I am a believer in revealed preferences, and for all angst from academia and NGOs about climate change, there is a lack of apparent urgency from most governments. Most of the environmental lobbying establishment is content to use the issue as a vehicle for fundraising than to propose actual solutions, and the IRA itself uses climate change as a vehicle for a smorgasbord of policies, such as domestic manufacturing and environmental justice. Last year, I predicted a major immanent reckoning for the climate movement, as the party must come to an end when learning curves falter and cannot deliver the goodies that various constituencies expect. It remains to be seen if there is any accuracy here, but if not a date, I stand by the general concept. I can only hope that the collapse of the mainstream climate movement comes quickly and opens space for some real solutions.

Quick Hits

Speaking of permitting reform, Austin Vernon has a piece at the Abundance Institute on streamlining solar permitting, as permitting obstacles, rather than panel costs, are now the most significant barrier to solar expansion. It is worth a read, and I can’t think of anything here to argue with. It is also good to see the Abundance Institute filling out its material.

Relevant to last week’s piece on electrofuels, there is a recent paper on methanol synthesis. The paper is very technical, but basically it discusses a new catalyst that will make methanol production more efficient. Electrofuels are mostly way too expensive for mainstream use today, but at least there is plenty of room for progress.

Now that Kamala Harris is the Democratic presumptive nominee, Republicans have been trying various attacks, such as JD Vance’s accusation that Harris and other Democrats are “childless cat ladies”. I dislike this not so much because it is a mean-spirited insult, though it is, but that it further politicizes child rearing, which is of critical societal importance. I wrote about this a few months ago. I argued in that piece that the loudest sectors of today’s so-called pro-natalist movement are more interested in using the issue for campaign and fundraising purposes, rather than coming up with anything that even remotely resembles a credible solution. My cat Natsu dislikes the remark too.

This week, I finished a playthrough of Final Fantasy XVI, which finally gets me caught up on the single-player main series games. Like the others in the series, it is quite good, though unfortunately it is very much not a kid-friendly game. I’ve decided that if I write a more comprehensive review, I will do so on another blog and link to it here. I do like to have a variety of topics, but there should be a limit on that.