The Problems with CAFE Standards

Today I would like to tackle the Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards for automobiles in the United States. We will consider the history of CAFE standards, the mechanics of them, how well they work in practice, and some practical problems. I am not necessarily against CAFE standards per se, but I will argue that fuel taxes or carbon pricing is a better route to achieve the goals that CAFE standards are meant to achieve.

History of CAFE

Like many energy policies that Americans are familiar with, CAFE was established in the aftermath of the 1973 oil embargo, and specifically in the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975. This major energy bill also established the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and efficiency standards for other kinds of products, which would later entail the familiar Energy Star program. CAFE was the first national policy to govern automobile fuel efficiency and remains the major policy for that purpose.

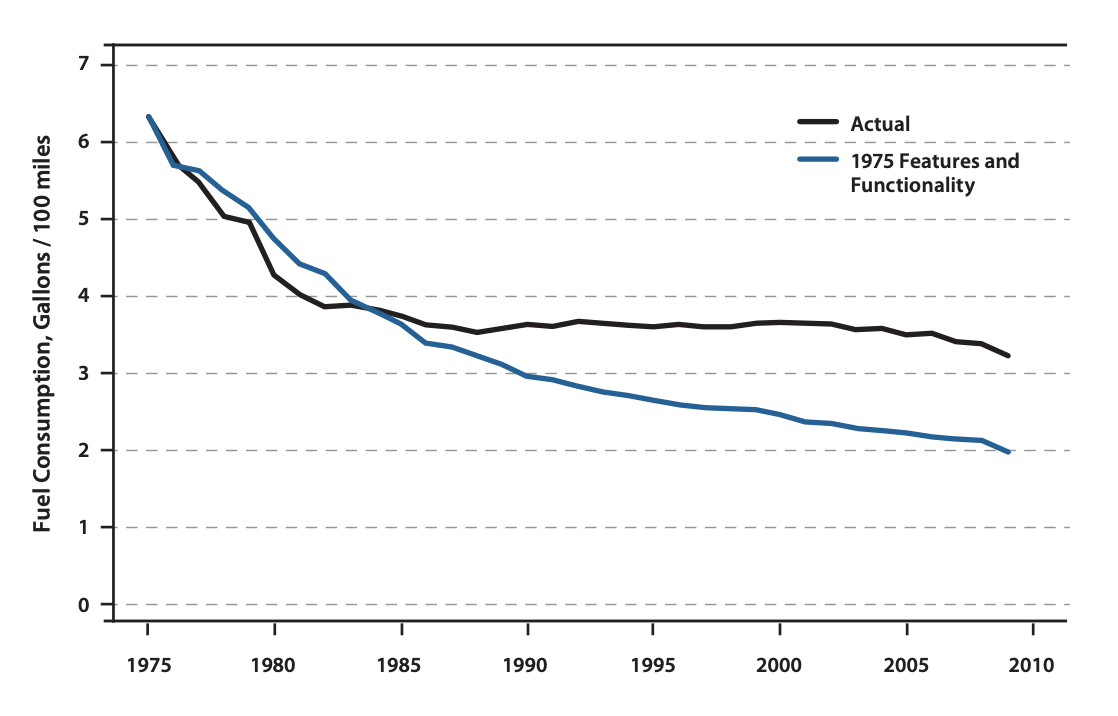

CAFE standards require, as the name suggest, that the average fuel economy of cars sold in the United States meet a certain level. CAFE standards first took effect for model year 1978 at 18 miles per gallon and increased to 27.5 MPG by 1985, where they (roughly) stayed until 2010. Similar, though less stringent, standards were established for light trucks.

The collapse of oil prices in the 1980s and 1990s diminished interest in CAFE. In the 2000s, interest in energy policy was revived by post-September 11 anxiety about energy security, growing concerns about climate change, and rising energy prices that culminated in 2008, and the favorable climate led to two major energy bills: the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007. The latter included the first increase in CAFE standards in decades, which were raised to 30 MPG for domestic model year 2011 and to 42.5 MPG by 2020. The standards of the 2007 law were exceeded by a 2009 agreement under the Obama administration with automakers and state regulators, using the Federal Government’s newfound authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the 2007 Massachusetts v. EPA ruling.

In 2023, the Biden administration proposed higher standards for passenger cars and light trucks beginning in model year 2027 and for heavy duty trucks and vans from MY 2030, rules that were finalized last March. The rule is under legal challenge (something that is not at all uncommon) and could change, especially depending on the outcome of the next election. The rule will raise the CAFE standards for passenger vehicles to 50.4 MPG by 2031.

It has long been the case that the EPA, which administers CAFE, has separate oil-equivalency measures of fuel efficiency for non-petroleum burning cars, especially electric vehicles. The new rule brings some technical changes to how these calculations are done, with the upshot that automakers will have to sell four times as many EVs to comply with the new standards. Relatedly, the Biden administration issued an executive order in 2021 that 50% of passengers cars and light trucks sold in 2030 are zero-emission. I have a hard time imagining how this will be met, but that is a discussion for another time.

It has also been the case since the inception of CAFE that there are different standards for passenger cars and light trucks (e.g. pickup trucks, SUVs), in part to avoid handicapping domestic manufacturers in favor of imports. This paper finds that footprint-based fuel economy standards create an incentive for larger vehicles, and this effect has subtracted 1.4 to 4.1 MPG from fuel economy compared to there being no size effect. CAFE standards are a reason, though far from the only reason, that cars in the United States have gotten bigger over time.

Weighing the Cost and Benefits

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that the new rules will add $932 to the cost of new passenger vehicles, due to added expense of automaker compliance. The NHTSA furthermore estimates that the new rules will save an average of $1043 in fuel over a vehicle’s lifetime. And so, even without attempting to monetize environmental benefits, the rule is a net financial gain. This study finds a negative net value of a 2018 proposal to reduce fuel economy standards. Consumer Reports finds that the NHTSA rule would have even greater benefits than the NHTSA itself estimates, and they wrote a favorable analysis of an earlier proposal to raise standards.

In 2003, the Congressional Budget Office considered whether stricter CAFE standards were warranted. The purpose of CAFE standards, after all, is to address the negative externalities associated with gasoline consumption. The two principle such externalities are environmental damages and national security degradation. The report finds that, as of 2003, gasoline taxes were, on average, higher than the external damages, which means that CAFE standards do damage on net. All this assumes that consumer behavior in the face of gasoline prices is rational; we’ll come back to that in a bit.

One obvious issue is that the financial benefits of CAFE are highly dependent on future gasoline prices, which are hard to predict. For example, this paper finds that the benefits of Obama era standard increases were much less than expected due to falling oil prices from 2014.

The most obvious question to ask, when it is shown that regulatory standards are net beneficial when considering strictly private costs, is why the regulations are needed in the first place. After all, if better fuel economy is a net financial benefit for the consumer, then people should buy more efficient cars without regulatory coercion. I find this to a common issue among energy efficiency proposals in general: white papers claims significant private savings, yet they fail to provide a satisfactory explanation of why the efficiency measures do not occur without regulation. In the case of CAFE standards, I see two plausible explanations. The first explanation is that consumers are not rational and in particular will, absent regulation, purchase vehicles that are less efficient than rational. The second explanation is that there are costs to the regulation that are not accounted for in the models. It is this second explanation that I gravitate toward.

Understanding Consumer Behavior in Car Buying

Let us first consider the question of rationality. Without having yet considered the second question, it is hard to know what kind of car a rational consumer “should” buy. But we can get at the question of rationality indirectly by considering consumer responses to changing gas prices. If the typical car buyer responds rationally to gas prices, then we should see a market shift toward more fuel-efficient vehicles when gas prices go up, and toward less efficient vehicles when prices go down. And that is exactly what happens. This paper finds a shift in buying behavior, induced by changing gas prices, that shows an implicit discount rate that is close to interest rates on car loans for those buyers who borrow. Which is exactly how it should be.

Now let us consider the question of unaccounted consumer preferences. SUVs constituted 48% of new car sales worldwide in 2023, a record high. Consumer preference for large vehicles partially explains the trend toward large cars over time, in contrast to the purported goals of CAFE regulations.

This meta-study finds a willingness to pay of $845 (2015 dollars) for a 1 second reduction of 0-60 miles per hour acceleration. Higher performance comes at a cost of efficiency, and therefore tighter efficiency regulations have a cost in performance, which can be measured by willingness to pay. However, bottom-up engineering cost-benefit analyses of CAFE standards generally fail to do so.

Of course, we can ask whether consumers should prefer size and performance. I don’t fully understand myself why these preferences exists. But they do. To ignore revealed preferences and write policy based on what we think people should prefer is a recipe for bad policy.

Why Carbon Pricing is a Better Solution

Several papers, such as this one and this one and this one and this one, have demonstrated that carbon taxes are significantly more efficient, as defined by a cost/benefit ratio, than CAFE standards in saving energy. I have not found a study that shows the opposite.

The reason why should be clear. Under fuel taxes or carbon pricing, commuters are left with many options to save energy, or not if that is the economically rational decision. They can carpool, take mass transit, forego non-essential trips, or drive sensibly. Buying fuel efficient vehicles may be a good option, but it is only one option among many, and not the only option, under carbon pricing instead of CAFE standards. And as noted above, CAFE standards have perverse effects, such as an incentive for larger vehicles and discrimination against efficient imports.

For this analysis, I drew heavily on a report by the free market-leaning Mackinac Institute. The report draws the same conclusion that I have: fuel taxes or carbon pricing is a far superior solution to CAFE standards. It is tempting to be jaded and suspect that a market-oriented think tank is only endorsing carbon pricing because they do not see it as a realistic option, and when the rubber hits the road, they won’t be there for a carbon tax. I can’t speak for Mackinac, but I can speak for myself, as someone who leans toward free market thinking, that I take carbon pricing very seriously.

I’ve said it many times before, and I’ll say it many times again. There is no credible route to decarbonizing the world economy that does not feature carbon pricing as the centerpiece. CAFE standards, when considered in isolation, may be good policy and they do bring about fuel savings. But they only nibble around the edges of the problem.

Quick Hits

Last year, I wrote a piece about green steel, which is steel that, as an alternative to carbon as a reducing agent, uses (A) hydrogen that is (B) produced by electrolysis that is (C) powered from low-carbon electricity. I wrote fairly enthusiastically about the potential for green steel, but I should have cautioned that the case is highly contingent on learning-by-doing cost reductions for hydrogen electrolyzers and solar and wind electricity. In recent months, I have been working on a large project on learning curves that has made me more skeptical that these cost reductions will materialize as hoped.

After months of limited movement and incremental Russian advances in Ukraine, in the last two days Ukraine has brought the war to the aggressor in the Kursk counteroffensive. As usual, the Institute for the Study of War has good coverage.

In Africa, the military juntas in Niger and Mali have cut relations with Ukraine after that country backed Tuareg rebels in Mali. I’ve commented on West Africa before and the threats posed by Wagner Group-aligned juntas in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The war in Ukraine has been internationalized, and that is all the more reason why it cannot be ignored.

And for something that I intended to comment on last week, there was recently a major prisoner exchange between Russia and Belarus and Western nations. We should celebrate that prisoners, especially Paul Whalen and Evan Gershkovich, are free, but the exchange came at a high cost, including returning the murderer Vadim Krasikov. This, and the Brittney Griner / Viktor Bout deal in 2022, raise serious concerns about rewarding Russian hostage-taking.

Also in the a-bit-late file, there was infamous scene from the opening of the Olympics on July 26, which was seen as making a mockery of the Last Supper. Whether that is the correct interpretation is disputed. I don’t find the argument in the foregoing piece to be very convincing, and regardless, the scene was clearly in poor taste. Still, I’ve been more bothered by the reaction of some Christians than by the scene itself. This has every appearance of yet another culture war issue that is meant to get the blood pressure up but is of no substantive importance. By way of context, over 800 million people worldwide suffer from malnutrition.

The reader may notice that this email is coming early in the morning, Pacific Time. I have started a new night shift job, and so my sleep schedule is now roughly the opposite of a normal person’s.