March 25, 2023

Synthetic Jet Fuel, Speculation and Commodity Prices, Operation Inherent Resolve, United 23.

Good afternoon. Here’s a long post for today.

Synthetic Jet Fuel

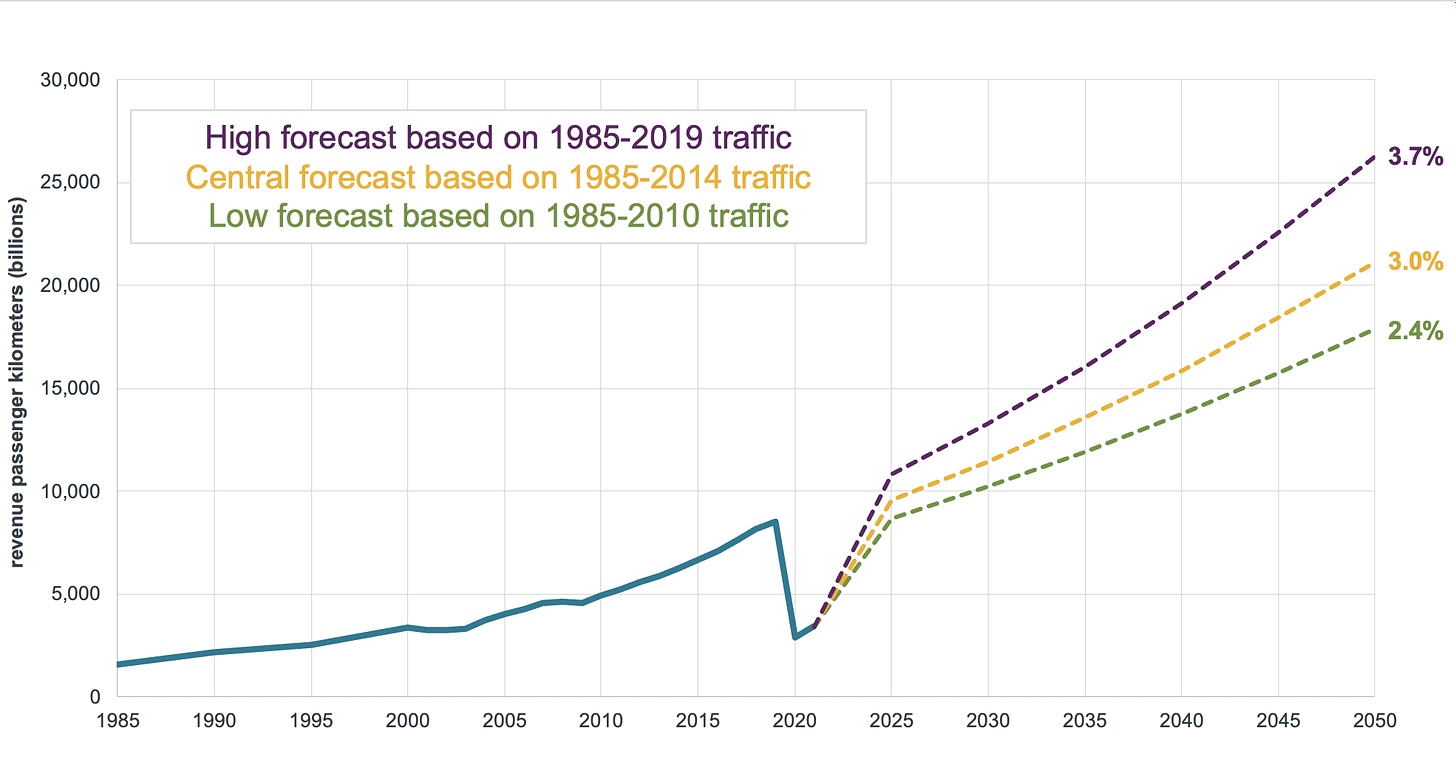

When we consider what a low-carbon, non-fossil fuel based energy system might look like, one of the most vexing challenges is jet fuel. Unlike with cars or trains, electric planes are not a viable option except for short, regional routes because batteries do not have sufficient energy density. Even ammonia and methanol might not have sufficient density. Drop-in jet fuel, which can be substituted for kerosene, may be the best option.

This paper points out that, aside from the energy density issue, another difficulty with any kind of fuel transition is that, during the transitional period, airports would have to supply two kinds of fuel, which would greatly complicate logistics. This transitional period would be long because aircraft have a capital lifespan of at least 20 years. Drop-in fuels, also called electrofuels or e-fuel, and what I am calling synthetic jet fuel or synfuel, solves this problem because it could be used with existing aircraft.

Also discussed in the aforementioned paper, one snag is that synthetic fuel is not a perfect substitute. Conventional kerosene contains aromatics, a type of organic compound that, despite the name, is not defined by smell. Aromatics are generally undesired, but a certain amount of them are needed due to the way aircraft O-rings are designed. Regulation (ASTM D7566) permits a blend of no more than 50% synfuel, and at least 50% regular kerosene, for jet fuel. Work is underway to modify the standards for 100% synfuel. I imagine this is doable, but the industry is understandably very cautious of changes that may affect safety. The Royal Air Force recently demonstrated a flight with 100% synfuel.

But cost is the real challenge. Before the oil price spike in 2022, kerosene cost around $2/gallon, which is roughly $650/tonne. It is estimated (converting currency and adjusting for inflation) that synfuel costs exceed $4100/tonne today and might reach $1720/tonne in 2050. Even with anticipated reduction, substantial environmental benefits are needed to justify the cost.

Excluding transportation, the carbon intensity of kerosene is about 3.16 kg for each kg of fuel. I’ll assume that synfuels are carbon neutral. That works out to a carbon mitigation cost of ~$339/ton, which exceeds any reasonable estimate of the social cost of carbon.

But there are additional benefits of getting rid of aromatics, since that cuts down on contrail formation. Contrails also provide an immediate global warming effect. Recent studies suggest that jet contrails cause twice the warming as CO2 emissions, and that low-aromatic synfuels could reduce contrail formation (if I read this paper correctly) by 50-70%. So we might crudely estimate that the contrail reduction benefit is equal to the CO2 reduction benefit, which would reduce the carbon mitigation cost to $169/ton. Still pretty steep, but it gets in range with the IPCC’s estimated social cost of carbon in 2050.

All in all, one has to squint pretty hard to make the numbers come out favorably for synfuels. If the world does in fact make a successful transition to a low-carbon energy system, aviation will probably be one of the last sectors to decarbonize.

As opposed to synfuels generated through electrolysis, aviation biofuels are a more preferred pathway for aviation synfuel at present, and a significant amount of blending already takes place. Aviation biofuels are at present cheaper than electrolyzed synfuels, but land use is a major environmental impact and barrier to expansion. Hydrogen is another option. Or rather than decarbonizing aviation directly, emissions could be offset by direct air capture or some other means.

The military is a special case. They tend to be less cost-sensitive than private industry, and fuel is a major logistical problem that alters the economic equation. In addition to the RAF, the U.S. Department of Defense is putting significant resources into synfuels. The military will be a driver of progress in this area.

Speculation and Commodity Prices

A colleague recently brought to my attention some work by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. The paper asserts (pp. 5-6) that speculation was a factor behind the food price spike in 2008. To support this theory, the paper cites this paper by Jayati Ghosh, which documents the price rise, documents the level of speculative activity in commodity markets in 2008, but does not meaningfully connect the two. Remember that if two trends occur at the same time, there is not necessarily a causal connection between them.

Basic economic reasoning suggests that speculation should not contribute to commodity prices. If speculators raise the price of a commodity above the clearing price (the price that the commodity “should” be based on supply and demand), then supply would be greater, and demand lower, than the “natural” value. This would cause inventories to rise. Fairly quickly, the price would have to fall below the clearing price to reduce inventories.

Basic reasoning can be backed by empirical evidence. In this paper, referring to the oil price spike at the same time, “We show speculation had little, if any, effect on prices and volatility”. A literature review finds,

A popular view is that the surge in the real price of oil during 2003-08 cannot be explained by economic fundamentals, but was caused by the increased financialization of oil futures markets, which in turn allowed speculation to become a major determinant of the spot price of oil. This interpretation has been driving policy efforts to tighten the regulation of oil derivatives markets. This survey reviews the evidence supporting this view. We identify six strands in the literature and discuss to what extent each sheds light on the role of speculation. We find that the existing evidence is not supportive of an important role of speculation in driving the spot price of oil after 2003. Instead, there is strong evidence that the co-movement between spot and futures prices reflects common economic fundamentals rather than the financialization of oil futures markets.

Looking at commodity markets more broadly, this paper finds, “that either there is no genuine overall speculation effect in agricultural, energy and metal markets, or the research design of the frequently applied GC [Granger causality] testing is not powerful enough to detect those effects”. More debunkings can be found here and here, though see this paper for a contrary view. And this and this and this papers provides a more mixed view. This paper highlights limitations of Granger causality, a key econometrics tools that underpins rulemaking following Dodd-Frank and much work on this subject.

Nevertheless, the belief in a major speculation-price nexus persists, also (incorrectly, see also this) in the housing market. Why is this? Part of the problem is that commodity supply and demand tend to be inelastic, especially in the short term. This means that supply and demand are not very responsive to price changes, and so a relatively small shock to either supply or demand can cause large price swings. People don’t understand this and so they imagine that prices must be somehow manipulated. There is also some scapegoating. Actual solutions for energy security, food security, and housing prices are difficult, and it is much easier to blame speculators, and few politicians can resist the temptation to do so.

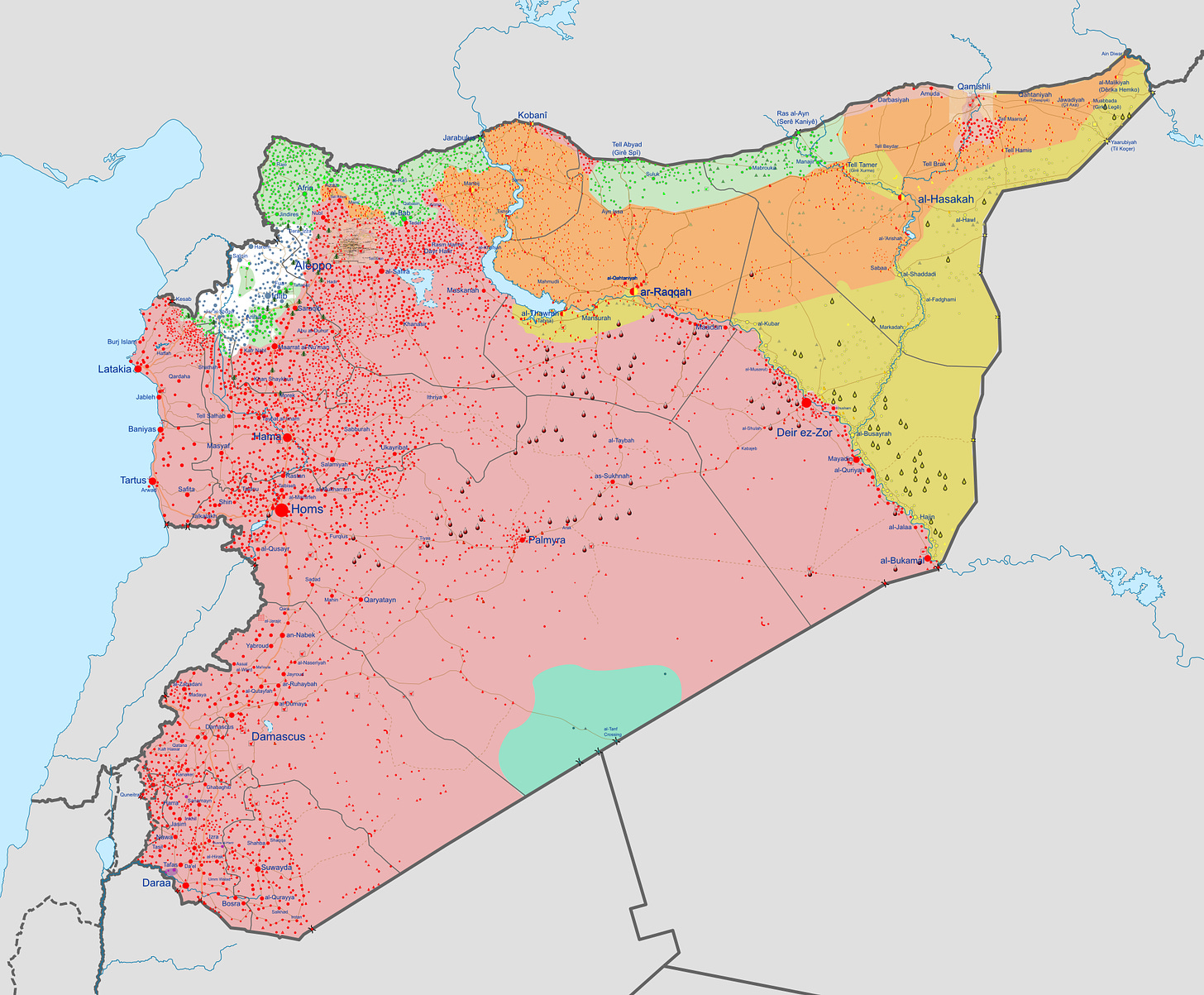

U.S. Mission in Syria

This week, there was an Iranian drone attack that killed an American in Syria and injured others, prompting Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to order retaliatory airstrikes. It is worth reviewing what the American presence is about.

The Wikipedia article gives a decent overview of the sequence of events. See also, the Congressional Research Service’s brief last month and a more detailed CRS overview from last November.

In 2011, protests emanating from the Arab spring devolved into civil war. The United States assisted rebels to fight the President Bashar Al-Assad and the Islamic State under the Syrian Train and Equip Program and the CIA’s covert Timber Sycamore, though neither of these programs were successful. In June 2014, the United States launched a coalition to defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Operation Inherent Resolve. Though centered in Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State operates in West Africa, Afghanistan and Pakistan, Central Africa, East Asia, and the Caucasus. They are the most threatening terrorist group in the world today.

By 2019, the Islamic State had ceased to control territory in Syria, and its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, had been killed. President Trump ordered a withdrawal of some American forces at that time, and had intended to withdraw completely, but due to opposition was persuaded to retain a residual force, which remains to this day.

Greatly complicating the matter is that, while Assad is a brutal dictator, the American response to his depredations has been waffling. In August 2013, the Syrian government launched a chemical attack on Ghouta, killing hundreds. Despite proclaiming a “red line”, President Obama wavered on retaliatory airstrikes and was bailed out, in the short term, by a deal with Russia to secure Syria’s accession to the Chemical Weapons Convention. However, following further chemical attacks, Russia refused to abide by the agreement to hold Syria accountable. See this from The Century Foundation for details on the subject. On April 7, 2017, the United States launched a cruise missile strike on the Shayrat Airbase in response to another chemical attack.

The Syrian government’s repression has caused an enormous humanitarian disaster, which has caused political problems in Europe and elsewhere. The intervention has strained U.S. relations with Russia over the latter’s support of the Assad regime; see this Brookings analysis for more on that. The intervention, especially the U.S. decision to back the Kurdish YPG, has strained relations with Turkey as well.

While weakened, ISIS is not gone, necessitating an ongoing U.S. presence in Syria. And while the emergence of ISIS caused the United States to deprioritize the threat posed by Assad, the threat and the history of brutality remain.

United 23

Could there have been a fifth airplane that was intended to be hijacked on 9/11?

As readers over the age of 30 surely recall, four airplanes were hijacked on the morning on September 11, 2001. They were

American Airlines 11, which was crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center,

United Airlines 175, which was crashed into the South Tower,

American Airlines 77, which was crashed into the Pentagon, and

United Airlines 93. Passengers, aware of the World Trade Center crashes, took back control from the hijackers. In the struggle, the plane crashed in Somerset Country, Pennsylvania. According to the 9/11 Commission, the intended destination was Washington, DC, likely either the Capitol Building or the White House.

A recent documentary from TMZ details suspicions by the pilot of United Airlines Flight 23 that terrorists were aboard his plane as well. The flight was scheduled from JFK in New York to Los Angeles. However, by my understanding the plane’s departure was late. While it was taxiing, the UA175 crash happened and the FAA ordered a ground stop, forcing the plane back to the terminal. Here is some more information about it, and some more.

I don’t regard any of the three news sources linked above to be reliable. TMZ specializes in celebrity gossip, with more than its share of sensationalized or outright fabricated “news”. I am not aware of any treatment of this issue from a reliable source. The 9/11 Commission doesn’t mention it at all.

Sometimes good information comes from unlikely places. The National Enquirer broke the John Edwards affair story for instance. But as far as I can tell, the TMZ documentary doesn’t introduce any new information, and I don’t regard these reports, which are anecdotal and based on memories of events that are now far in the past, as trustworthy. But I am still bothered by the lack of authoritative information. Even a rebuttal would be valuable.

Reference to “unanswered questions” about 9/11 undoubtedly triggers associations with baseless conspiracy theories, but disassociation with conspiracy theories does not imply that all important information is known. What really happened with UA23 is one such question. Much more serious is the degree of complicity of officials in the Saudi government, a topic that more than 20 years later, Americans have yet to adequately grapple with.