Lessons from the Dust Bowl

I would like to discuss agriculture again this week, but this time moving beyond food loss and waste. Over the last month, I touched on many issues around agriculture that I could only discuss briefly, and then only in the context of food loss and waste.

One issue in particular that I do not feel was done justice is mechanized farming, which I discussed for its potential to reduce postharvest losses. But there is much more to farm mechanization than labor and yields, including some important controversial aspects. And I think the best way to deal with the complexity is to examine an historical episode that, particularly for Americans, looms large in our consciousness.

The Dust Bowl is, of course, itself a highly complex event. Today, we will consider how the Dust Bowl came about; how agricultural practices of the late 19th and early 20th centuries caused it; and what we have learned about farming, migration, and government responses to disaster.

Origins of the Dust Bowl

The importance of Western expansion in American history is something that is hard for a contemporary person to appreciate, particularly with today’s intellectual milieu of anti-colonial sentiment. The term “manifest destiny” was coined by the partisan newspaper editor John L. O’Sullivan in 1845, well after the British establishment of colonies on the eastern seaboard, the Louisiana Purchase, and many other expansions of United States. O’Sullivan used the term to argue for annexing Texas, and Democrats quickly seized on Manifest Destiny as a slogan for expansionism toward the Oregon Territory.

Acquiring land was one thing, and settling and utilizing the land was quite another. The U.S. federal government has implemented several Homestead Acts, from 1841 to the New Deal era, notably the Homestead Act of 1862. An expanded Homestead Act had been a high priority for the short-lived Free Soil Party, and then the Republican Party, and the circumstances of secession opened political space to pass legislation.

The 160 acres afforded by the 1862 law may seem generous, but conditions on the dry plains of the West rendered it difficult for families to support themselves. The situation greatly improved with the Railroad Act shortly thereafter, culminating with California Governor Leland Stanford driving the Golden Spike on May 10, 1869, completing the first transcontinental railroad. The refrigerated rail car was especially crucial in allowing farmers and ranchers to bring their products to markets in the growing metropolises of the late 19th century.

The 19th century also saw the Industrial Revolution come to the farm. Among the many manifestations are Cyrus McCormick’s reaper, patented in 1834. The first practical combine (so named because it combines several harvesting operations—reaping, threshing, winnowing—into a single process) was patented in 1836. A steam engine replaced animals as the source of power in the 1880s, and the J.I. Case and John Deere tractor-pulled combine came in 1927.

Despite these advances, the aridity of the Plains, relative to the East Coast, remained a challenge that was tragically not well understood before the 1930s. The phrase “rain follows the plow” was coined by Charles Dana Wilbur in 1881, and it holds that tilled soil would absorb more moisture, which, as the soil dries, would be fed back into the climate as increased rainfall. This novel terraforming theory, which several railroads used to market land, had some superficial plausibility as wetter years corresponded to post-Civil War migration, but it was discredited with a drought in the 1890s.

Markets were as capricious toward farmers as the weather. Due to the disruption of World War I, the price of wheat jumped from $0.78 to $2.12 per bushel from 1913 to 1917. Average prices were $2.16 in 1919, but with the end of the war, they crashed to $1.03 by 1921. The government responded with several pieces of legislation, including McNary-Haugen bills that were vetoed by President Coolidge, and then the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which President Roosevelt signed in 1933.

High wheat prices in the 1910s motivated farmers to plant as much as they could. Deep plowing, along with cattle grazing and burning to control weeds, removed the grasses that held the soil together. When prices fell again with the onset of the Great Depression, farmers made up for lost income by planting even more wheat.

An exceptional drought began in 1930-1931, with 1934, 1936, and 1939-1940 also particularly bad years. The stage was set for the worst ecological disaster in American history.

Disaster Unfolds

The term “Dust Bowl” is used broadly, referring to the series of disasters throughout the 1930s, though there were several distinct events. Geographically, the most severe drought was on the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles, western Kansas, eastern Colorado, and northeastern New Mexico, though the entires Plains region was affected.

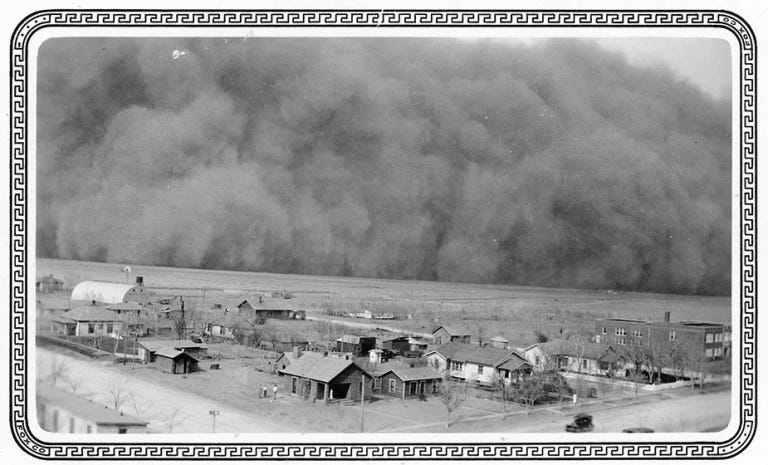

Crop failures began in 1931, and also in 1931 was the first of several dust blizzards. These are events in which desiccated topsoil, no longer held in place by grasses, was picked up and blown by the wind. The worst dust blizzard occurred on “Black Sunday”: April 14, 1935. On this aptly named day, dust was so thick around the Texas and Oklahoma panhandles that the sun was entirely blotted out, and visibility was reduced to three feet. Dust was transported as far away as Washington, D.C. and provided a convenient boost to proponents of the soon-to-be-passed Soil Conservation Act.

During 1935, 850 million tons of topsoil blew off the Southern Plains, more than the 540 million tons of ash that were released in the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens. Dozens of dust storms continued through 1941. At the peak year of 1935, 100 million acres of farmland were affected; there were 1.2 billion acres of farmland in the United States in 2012. Many of the hardest-hit farms never went back into farming.

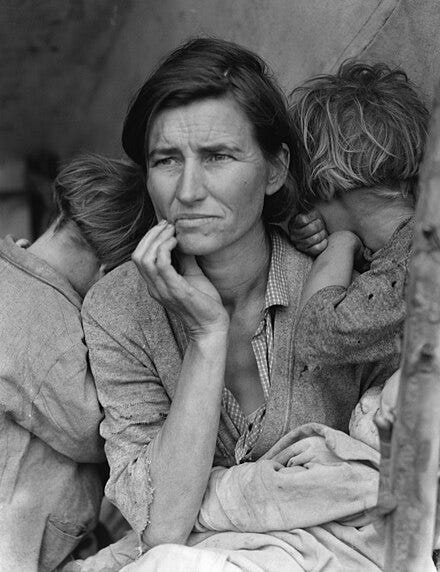

About 7,000 people died from the storms, mostly from diseases caused from dust inhalation. The Dust Bowl created 2.5 million refugees from the Plains States, of whom 200,000 settled in California. No doubt there are some readers with ancestors who were affected in this way.

As noted above, Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which was intended to stabilize prices as a form of aid to farmers that were struggling during the Great Depression. Under the AAA, six million pigs were slaughtered with the meat wasted, and 10 million acres of cotton were plowed under. At a time when hunger was widespread, these actions did not sit well with the public. The AAA was ruled unconstitutional in 1936 and replaced with a new AAA in 1938, which remains in effect. Also to provide relief for farmers, the Resettlement Administration encouraged farmers from the hardest hit areas to move to less dry areas of the Great Plains, and it provided additional poverty relief. The Resettlement Administration was followed by the Farm Security Administration.

Also as noted above, in 1935, Congress passed and FDR signed the Soil Conservation Act, which established the Soil Conservation Service within the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The SCS was renamed the Natural Resources Conservation Service in 1994 to reflect a broadened scope. For erosion control projects, the SCS employed labor from the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Works Progress Administration, and the Civil Works Administration. The Flood Control Act of 1936 expanded the SCS’s mandate to flood control projects for vulnerable watersheds.

Also to control erosion, the federal government responded with the Great Plains Shelterbelt, which planted 220 million trees by 1942. The Shelterbelt was effective in reducing erosion, a benefit when continued into the following century, though the trees conflicted with irrigation and other agricultural uses.

After enormous economic and human tolls, the Dust Bowl left permanent imprints on popular culture, such as Woody Guthrie’s ballads and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, which vividly portrays the travails of migrants from Oklahoma. We have also learned much about managing moisture and erosion on dry farmland, with soil conservation practices now standard in a way that they weren’t prior to the 1930s. Now we will take a closer look an erosion control, and particularly the role of mechanization.

Mechanization and Erosion

The Dust Bowl shortly followed the widespread usage of large, powered equipment, and so naturally the role of mechanization has been scrutinized for making the soil vulnerable to erosion.

The mechanism of concern is compaction. Heavy equipment causes the soil to compact, particularly at deeper (>50 centimeters) layers, which inhibits the soil’s ability to absorb nutrients. This damages productivity, causes runoff, and makes the soil vulnerable to erosion. Focus groups in several countries in Africa have identified this as a problem. The phenomenon has been observed in vineyards in Catalonia, Spain. Advocates against industrialized agriculture more broadly have seized upon the compaction issue.

However, the relationship is not straightforward. A recent study in China has found that mechanization improves “agricultural environmental efficiency”, which is an agglomeration of several environmental metrics. In particular, the study found that erosion in China decreased by about a third from 2010 to 2021, with mechanization increasing significantly over that time period.

It would be imprecise at best to say that mechanization caused the Dust Bowl. One would be on firmer ground in arguing that mechanization enabled the bad practices that, along with drought, contributed to the Dust Bowl. Although the drought of the 1930s is the worst in recent history, there have been more droughts since then, and nothing like the Dust Bowl has recurred. The Depression and Dust Bowl were impetuses for conservation measures such as cover cropping, terracing, and many others. This was done without going back to mostly manual labor.

A Migrant Crisis

The most visible manifestation of human suffering from the Dust Bowl was a large-scale exodus of farmworkers who, socked from both the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, had to look elsewhere for their livelihoods.

The 2.5 million refugees from the disaster did not find a warm welcome at their destinations. Though the term existed before, “Okie” (and related terms like “Arkie” and “Tex”) became a slur for migratory agricultural workers. California in particular, a popular destination for people fleeing bad conditions, took harsh actions against refugees. In 1936, the overzealous Los Angeles Police Chief Jim Davis ran the “Bum Blockade”, interrogating those who crossed the border with Arizona and turning back or placing in concentration camps those who could not prove California residency. This operation lasted for two and a half months.

In 1937, California passed an “anti-Okie” law, which made it a misdemeanor to assist a poor person in entering the state. The law lasted until 1941, until the Supreme Court ruled in the 9-0 Edwards v. California decision that the law was unconstitutional. Grounds for the ruling were Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution, particularly the Commerce Clause, and also that to freely traverse state borders is an implied right of a U.S. citizen, and thus California’s actions violated the 14th Amendment.

States legally cannot directly block migration from elsewhere in the United States, but less direct means, such as strict zoning and urban containment, are widely used. I find it odd that such policies have not received greater legal scrutiny.

Although the actions described here are legally and morally indefensible, one should remember that California, like much of the rest of the world, was itself mired in the Depression. Although we might not like to admit it, much of our moral magnanimity results from abundance, and poverty is morally coarsening.

Finally, nowadays immigration restrictionist rhetoric tends to revolve around international migration, and it is argued that only citizens of one’s own country should be regarded as morally significant for the purposes of legislation. But California’s various anti-Okie policies are but one of many examples showing how nativism can just as easily be turned against one’s fellow citizens.

Can It Happen Again?

Nothing like the Dust Bowl has occurred anywhere in the world since the 1930s. Aggressive soil conservation measures driven by dire conditions of the Dust Bowl, as well as the environmental awareness of the 1970s, have made Plains agriculture far more environmentally conscious than it was prior to the 1930s.

On the other hand, it is feared that climate change will exacerbate heat waves and droughts in the Plains. So far, no drought on the scale of that of the 1930s has occurred since, but it obviously could. The Plains also relies heavily on irrigation from the Ogallala Aquifer, which faces long-term depletion.

But I think another Dust Bowl unlikely, at least as long as ingenuity is free to combat the problems that face agriculture today.

Quick Hits

Germany is a nation historically renowned for engineering prowess and feared for … you know. But the German edge is slipping away, argues Sabine Hossenfelder. Internet infrastructure is not that good, trains are unreliable, and Germany continues to make monumentally foolish decisions with energy policy, especially the nuclear phaseout. Squandering those advantages will no doubt prove much easier than getting them back.

Andrew Ng wrote in his latest newsletter, The Batch, about California’s SB 1047, a piece of legislation that would hold developers of artificial intelligence models responsible for harms that may result from them and would create a state oversight board. Ng believes, as do I, that this is a foolish piece of legislation, and he goes into some detail as to why. Ng has argued in previous newsletters that, insofar as AI is to be regulated, regulation should focus on applications and not base models. We don’t hold manufacturers of electric motors liable if those motors are used for nefarious purposes.

Several news articles have recently taken a sour line on electric vehicles, which I find hard to understand. Maybe people conflate EVs with Tesla and thus Tesla’s troubles, which is becoming less accurate as Tesla’s market share has slipped below 50% (disclosure: I am an owner of Tesla stock). The adoption of EVs is occurring more slowly that many advocates would like, but by all evidence it is still occurring.

I mostly wrote this post yesterday and earlier today, before the apparent assassination attempt against Donald Trump. If I have anything to say about it, that will wait for next week.