Learning Curves, Dispatches from Markets & Society

I was out last week at the Markets & Society conference and skipped my usual post. While there, I presented on the subject of learning curves for use in energy policy, and how they can be misapplied. Today I’ll talk about my work with learning curves, and then I’ll briefly discuss some other interesting items from the conference. Before proceeding, I offer my gratitude to Josh Smith, for organizing the panel session on electricity policy and inviting me to present there, and to the Mercatus Center at George Mason University for putting on the conference.

My work on learning curves is based on a paper I wrote throughout much of 2024 and am now finalizing to submit to the conference journal. I’ll link the full paper once it is done and published, or if it is not published, I’ll share it in a different form.

What is a Learning Curve?

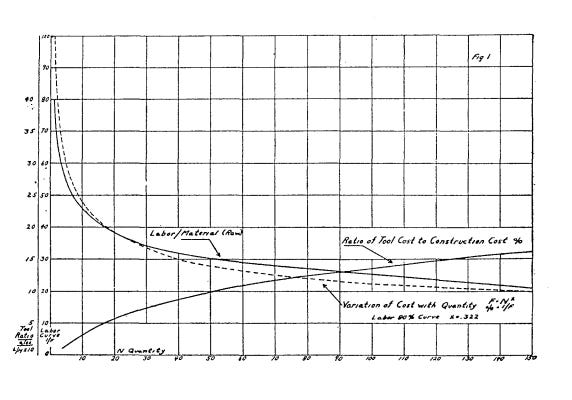

We should start with what learning curves are. A learning curve is a regular relationship between the cumulative production of some good and the price. The idea should make intuitive sense: as individuals, we get better at a task by doing it repeatedly; “better” means more efficiency and fewer errors. In 1936, Theodore Paul Wright observed a similar pattern with airplane production. For every doubling of cumulative production, the price of manufacturing an airplane falls by about 20%, a quantity known as the progress ratio. In honor of the landmark paper, this pattern is sometimes referred to as Wright’s Law or the Wright curve.

Over the subsequent century, the learning curve would go on to become one of the most studied phenomena in econometrics. The related phrase experience curve was introduced by Bruce Henderson, founder of the Boston Consulting Group, and Henderson later found a typical progress ratio of 0.1 to 0.15 for the labor cost of a good and 0.25 for the financial cost.

The learning curve can be expressed mathematically as follows.

Here, c_n is the average cumulative production cost of n units of production (the literature is sometimes sloppy about distinguishing between the average cumulative production cost of the first n units and the cost of the n’th unit), c_0 is the initial cost, and beta is the learning rate. The progress ratio, as described above, can be expressed as 2^(-beta).

Learning curves are widely applicable across industry, but in recent years, learning curves have been used particularly heavily with energy technology, and in particular, with technologies associated with decarbonizing the world energy system. To give just a couple examples, in 2006 there was the landmark Stern Review of The Economics of Climate Change, which concluded,

This Review has assessed a wide range of evidence on the impacts of climate change and on the economic costs, and has used a number of different techniques to assess costs and risks. From all of these perspectives, the evidence gathered by the Review leads to a simple conclusion: the benefits of strong and early action far outweigh the economic costs of not acting.

This conclusion is predicated heavily on learning curves to model the cost trajectory of key technologies.

Many other models of an energy transition, such by Way et al., also predicate their forecasts on learning-by-doing effects.

The other example to highlight is Stripe’s investment in direct air capture. As the name suggests, DAC is a technology that captures carbon dioxide from the ambient atmosphere, which can then be sequestered or used for some other purpose. Theoretically, DAC at a sufficient scale entirely solves the climate change problem. It is hard to determine exactly what the cost of DAC is today, since it is a nascent technology and estimates vary widely, but most hold that DAC is too expensive today for widespread use. This study from 2024 says the cost is $230-540 per ton of captured CO₂, well above most mainstream estimates of the social cost of carbon and the cost of many other mitigation measures.

However, Stripe is optimistic that the price can be lowered to something that is feasible at a large scale.

This thinking [about learning curves] shaped Stripe’s initial purchases and ultimately led us to launch Frontier, an advance market commitment (AMC) to buy carbon removal. The goal is to send a strong demand signal to researchers, entrepreneurs, and investors that there is a growing market for these technologies. We’re optimistic that we can shift the trajectory of the industry and increase the likelihood the world has the portfolio of solutions needed to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

I am not disputing the existence of learning curves. The phenomenon is very real, and it is appropriate for energy modelers to take into account the learning effect. However, there are several reasons why the benefits of learning are less that they initially appear, and these are important caveats for technology modelers and policymakers that are all too often ignored. Here, I will focus on five keys issues.

Five Challenges to the Learning Curve

I’ve identified five main reasons why one should be cautious about using learning curves to model prices of energy technologies, and especially cautious about using them for policies such as setting subsidies.

The first challenge is properly measuring learning rates. At first glance, the problem seems straightforward because for many industrial products, price and production time series data are readily available. Söderholm and Sundqvist find that it is not nearly so straightforward. There are many exogenous factors that affect prices, such as commodity price shocks. Modelers attempt to control for these hidden variables in different ways, which results in widely divergent observed learning rates for the same technology. More recently, Grafström and Poudineh have observed similar problems in measuring learning rates for wind and solar power in particular.

Sagar and Van der Zwaan observe that there is a survivorship bias in learning rates. Those technologies that do exhibit strong learning are more likely to survive, and thus to be studied by academics, than those that do not. Therefore, a literature review such as what I have done is likely to show learning rates that are biased upwards.

The second challenge, closely related to the first, is that it is difficult to establish causality between production and price reductions, a problem that Matt Clancy illustrates very well. He considers specifically Swanson’s Law, the observation that solar photovoltaic prices tend to decrease by about 20% for a doubling of installed volume, an application of the learning curve. As Clancy demonstrates, a story could plausibly be told that flips the direction of causality. Maybe prices fall due to exogenous technological advances, and falling prices cause deployment to accelerate.

The latter scenario might be called Moore’s Law, which is the observation that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit tends to double about every two years. In work with the Santa Fe Institute, Nagy et al. consider whether Wright’s Law; Moore’s Law; the Goddard model, based on economies of scale; and various combinations of these models yield the best price forecasts. The authors find that the Wright model performs the best, but Moore’s Law is only slightly behind. The results are based on a database that was produced by the Santa Fe Institute of 62 price and production time series for various products.

The third challenge is that there is robust evidence that learning rates tend to decline as a technology becomes more mature. Anzanello and Fogliatto review several other mathematical models, many of which show declining learning rates over time, often rates that decline to zero, meaning that the price converges* to some nonzero floor with great amounts of production. Boone argues that a model of declining learning rates forecasts prices better than constant learning rates in the context of procurement by the United States Air Force.

There are many interesting papers, such as by Ferioli et al., that posit a component-based learning model. By this, they mean that the cost of some product should be treated as the sum of several components, each of which may have different learning rates. It can be shown that in a composite model, the overall learning rate declines to whatever the lowest learning rate is among the components, as the authors argue in the context of solar PV, wind turbines, and carbon capture.

A special case of this is incompressibility, a constant term that is added to the Wright model, as described by Johnson in the context of U.S. Defense Department procurement. With incompressibility, the learning rate declines to zero.

I haven’t found a paper that argues this point, but I wonder, in the context of the Sagar and Van der Zwaan paper on survivorship bias, if declining learning rates might be a reversion to the mean.

The fourth challenge has to do with transfer learning, and this is especially a challenge for technologies that are at an infant stage. With a new technology, especially one closely related to a more established technology, it should not be assumed that cumulative production starts from zero, but rather takes advantage of the learning that was achieved with the mature technology. Malyusz and Pem find that a model that incorporates prior experience tends to perform better than one that does not.

To show where things can go wrong, Previsic and Epler consider wave power, a technology that was at a pre-commercial state in 2012, when the paper was published, and still is. They model that the price of wave power should decrease by 15% for every doubling of installed capacity, and since installed capacity was starting from a very small base, there should be rapid initial cost declines. Wave power is advancing, albeit slowly, and it is now clear that Previsic and Epler’s model was too optimistic. A similar problem is observed with offshore wind, and I fear that we may see similar disappointment with direct air capture.

The fifth and final problem, as Bläsi and Requate discuss, relating specifically to the use of learning curves as basis for subsidy, is the need to disentangle when the learning effect is a private benefit and when it is a knowledge spillover that might merit subsidy. There does not appear to be consensus in the literature as to how to deal with this issue. Irwin and Klenow, for instance, looking specifically at DRAM semiconductors, find that firms learn three times as much from their own production (private learning) as they do from that of other firms (knowledge spillovers). They further find that knowledge spillovers are as great between firms internationally as the are between firms in the same country (Japan, in the case they consider), which casts serious doubt on the merits of the idea of the government subsidizing a strategic industry specifically for the purpose of boosting national advantage. By contrast, though, Castrejon-Campos et al. find differential spillovers between domestic and international firms, which leave a small bit of daylight for a role for industrial policy.

Conclusion

I don’t really have a snappy conclusion for all this, but one point that is very obvious from my research is modelers, and especially policymakers, need to be much more careful about their use of learning curves. There is an especially reckless use of learning curves, called solar triumphalism, which holds that solar PV in particular has experienced rapid learning curve-induced price declines, assumes that the price declines will continue into the indefinite future, and therefore other decarbonization options should be rejected.

Large swathes of energy policy—Americans may be familiar with the Production Tax Credit, Investment Tax Credit, and Renewable Portfolio Standards, among others—are predicated on the expectation that these policies will lead to cost reductions that are socially beneficial knowledge spillovers. These policies are more politically palatable than carbon pricing, but if the benefit—and social benefit in particular—of learning curve cost reductions is overestimated, then these policies start to look ill-advised. And so, I will conclude by reiterating a view that I have expressed in many previous posts: if we really want a low-carbon energy system, then there is no viable shortcut to carbon pricing.

I hope to have a final draft of the full paper ready in the next week or two, and somehow or another I will share it with anyone who is interested.

* Technically, it is possible that both the price and learning rate converge to zero, but this is not common is published models.

Dispatches from Markets & Society

Last week was the first academic conference I have attended in many years, and though it was an exhausting experience (as you might deduce from the timestamp of this post, I still haven’t gotten my sleep schedule on track), it was very worthwhile. The conference was hosted by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, a libertarian-ish economics group that is associated with such researchers as Tyler Cowen, Alex Tabarrok, and Bryan Caplan. It took place at the Fairview Park Mariott hotel in Fairfax, Virginia, nestled in an office park populated heavily by defense contractors and trees.

The conference ran from October 11-14, though due to a snafu with my returning flights, I had to skip the last day. Rather than attempt a full run-down, I’ll highlight a few things that I found especially interesting.

I presented on Saturday morning at a panel on energy and electricity policy. Josh Smith of the Abundance Institute organized the panel and presented on rent-seeking aspects in capacity markets. Mark Van Orden spoke about political contributions from electricity utilities and argued that these comprise rent-seeking behavior, as shown by an increase in gold-plating infrastructure and rising electricity prices. Michael Giberson of the R Street Institute was scheduled but did not make it to the conference.

Also on Saturday morning, there was a panel discussion on theological perspectives on the market, which included Erik Matson on Reinhold Niebuhr, Jordan Ballor on the French Calvinist Auguste Lecerf, John Robinson on C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce, and Elisabeth Kincaid on Pope Leo XIII, whose papacy was from 1878-1903. I found especially interesting C.S. Lewis’ perspective on post-scarcity. According to Robinson, Lewis was a critic of visions of post-scarcity, and he portrayed a post-scarcity society as hell, with people being driven apart.

Mario Small gave a fascinating keynote address on payday lenders and the apparent racial gap in how these institutions are seen. I’m guessing that not many readers of this blog have direct experience with payday lenders, and for most of you, what you have read in the press has been mostly negative (if you have had an experience, I would be interested in hearing about it). Small considers whether proximity and exposure influence attitudes, and he notes how much more emphasis payday lenders place on customer service compared to traditional banks.

Nava Ashraf gave another keynote on trust in markets, with Zambia as a case study, and how trust is essential for the flourishing of female entrepreneurship. This seems particularly relevant with this year’s Nobel Prize in Economics going to major figures in institutional economics.

In another panel on the market-state divide, Vincent Carret spoke on how the state has displaced entrepreneurs as a guarantor of full employment, such as articulated by Alvin Hanson’s secular stagnation thesis. Hanson’s Fiscal Policy & Business Cycles argues that permanent deficits as a form of government stimulus are now required, a policy that the American government has taken, with likely eventual dire consequences.

In the same panel, Diana Thomas discussed St. Thomas Aquinas and the Vienna-Virginia tradition. She discussed Patrick Deneen’s book, Why Liberalism Failed, which is a major intellectual influence in the post-liberal New Right, including Republican Vice-Presidential candidate J.D. Vance. According to Thomas, many Christian critiques of capitalism make the error of conflating capitalism with atomism, and she responds by discussing the work of Mary Hirschfeld, bridging economic thought with the work of Aquinas.

Finally, Greg Robinson gave a fascinating talk on unifying Christian values with a humanistic and capitalist worldview. This is an important corrective both to a modern intellectual impulse to sideline religion from public discourse and to the impulse among some Christians to reject humanism and embrace theocratic politics.

That’s enough for now. Conferences of this nature can be like an all-you-can-eat buffet. I want to try everything, but I know I will get sick if I attempt to do so. The conference wasn’t really as theology-heavy as this review might make it seem, but those were the sessions I gravitated toward.

Quick Hits

What, this post isn’t long enough already?

Ted Nordhaus at the Breakthough Institute spoke about the abundance movement, and how it is diametrically opposed to the neo-Malthusian orientation that characterizes the mainstream environmental movement. He uses the word “environmentalism” in a similar way to how I use the word “ecologism”, as I regard the latter, but not the former, as an inherently anti-modern philosophy. As positively disposed as I am toward ideas associated with the burgeoning abundance movement, I have been burned enough times by ideological commitments to be careful about making one toward them.

In a related post a few days later, Ted considered the potential for violence from the environmental movement. This is something that I especially fear now, if a handful of environmentalists feel the need to make a desperate move in the face of declining political influence. The embrace of violence is a Rubicon; once you’ve done it, there is no way to walk back.

Sabine Hossenfelder discusses her skepticism about the transformative role of artificial intelligence in software engineering, a skepticism that I partially share but suspect is overstated, as it fails to account for future developments. She discusses this paper, which finds modest productivity increases and an increase in the number of bugs associated with use of Github Copilot.

U.S. officials recently announced that an ISIS-K Election Day terrorist plot was foiled. The Khorasan Province (Afghanistan and Pakistan) of the Islamic State, ISIS-K is responsible for several major terrorist attacks, including the Kabul Airport attack in 2021 and the Crocus City Hall attack in Russia earlier this year that killed 130 people. Ever since the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, I’ve predicted that we’ll be back, and for the same reason that we were there in the first place.

And finally, long-time video game music composer Nobuo Uematsu has announced his retirement from the industry. Uematsu is best known for his work on the Final Fantasy series, having been the sole composer for the first nine games and partial composer for X, XI, XII, and XIV. I don’t consider it an exaggeration to characterize Uematsu as one of the greatest composers in history or to suggest that the Final Fantasy series would not have been successful without his work. A sampling of his music can be found here.