July 15, 2023: The Problem with IPAT

Good afternoon. Today we are going to look at the I=PAT equation in environmental science.

I=PAT is a deceptively simple equation: Impact = Population × Affluence × Technology. Impact measures the magnitude of some environmental concern, such as greenhouse gas emissions or sulphur dioxide pollution. Population is straightforward. Affluence can be expressed as gross domestic product per capita. Technology is the impact per unit of GDP (impact / GDP), and it is the most difficult term to understand. The label “technology” suggests that the technology for things such as energy generation or food production is the most important factor, but this term entails a complex mix of factors that are difficult to quantify. It is highly reminiscent of the residual term (AKA total factor productivity) in the Solow growth model.

To my knowledge, the earliest formulation of I=PAT is in a 1971 paper by Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren. If it wasn’t obvious already, these names should indicate where this discussion is headed.

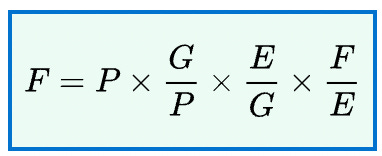

Specifically for greenhouse gas emissions, a modified equation known as the Kaya Identity is usually used. Developed by the Japanese energy economist Yoichi Kaya, the Kaya Identity expresses greenhouse gas emissions (from energy) as the product of four terms:

Before we get into the problems with these equations, they do yield some interesting insights. But before that, a few clarifications. The Kaya Identity is used to measure greenhouse gas emissions from energy, not total emissions. According to the recent Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy, energy constitutes about 87% of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, with the remainder from land use, industrial processes, and other sources. I will be discussing “energy” in terms of primary energy as defined by the EI, though this is not strictly necessary.

One obviously sees greenhouse gas emissions continuing to go up, though at a slower rate in the 2010s compared to the previous decade. Events such as the 1970s oil crises, the early 1980s recessions, the 2008 financial crisis, and COVID-19 can be seen but look like mere blips. The population trend looks like a straight line, though if you squint, you can see the impact of COVID-19—for which the official death toll worldwide as of this writing is about 7 million people and actual death toll as much as four times higher. I don’t know for sure where the EI’s population figures come from, but I would guess they are from World Population Prospects, and as the demographer Yi Fuxian has demonstrated, there are reasons to suspect that the numbers are inflated at least for China and India.

I also find it interesting that over the 1965-2022 time frame, energy efficiency has had about twice the measurable impact as clean energy deployment, with the gap moving in the favor of efficiency over time. Despite this, hopes for deep decarbonization tend to revolve primarily around clean energy deployment, e.g. building solar, wind, and nuclear plants.

Ehrlich and Holdren are noted advocates of population control, and the “P” term in I=PAT was clearly of the greatest interest to them. The “A” term is also of great interest to degrowth advocates. And so it is time to discuss why this equation is flawed to the point of near uselessness in policymaking.

Of course, I=PAT and the Kaya Identity are true in a tautological manner, at least as long as none of the terms in the denominators are zero. But the equations mislead by presenting the terms as both meaningful and independent quantities. An absurd illustration makes this point.

Greenhouse gas emissions can also be expressed in this modified form of I=PAT, where I is Impact (GHG emissions), P is annual number of Pirate attacks, A is the number of Avocados grown worldwide per pirate attack, and T is Technology, or the amount of greenhouse gas emissions per avocado grown. This expression of emissions is also tautologically true, but it is clearly useless. Why is it useless?

It is useless because the variables are dependent in such a way as to provide no information on policy interventions relevant to reducing emissions. If world governments, concerned about the role of P is driving emissions, agree to increase enforcement against piracy, then A will increase inversely to the decrease in P, and there will be no impact on I. Likewise, if concerned about the role of A, governments agree to ban the growing of avocados, then T will increase inversely to the decrease in A, again resulting in no change to I.

Likewise, there are interdependencies between the terms in I=PAT and the Kaya Identity that make the naive linear relationships suggested by these equations too far off to be useful. Let’s look at some of these interdependencies.

Between population and wealth, Malthusian and Kremerian hypotheses can be put forward. The Malthusian hypothesis, deriving from Thomas Malthus’ work on population in 1798, holds that an increasing population will cause greater competition for resources such as farmland and lower the average standard of living. The Kremerian hypothesis, named for Michael Kremer in his work on long-run economic growth, holds that population growth will increase the average standard of living because more people means more researchers and opportunities for trade (agglomeration effects). The former point is also made by Julian Simon. Historical evidence can be mustered in favor of either hypothesis, but I have argued in the past that, at least since the Industrial Revolution (incidentally, at the dawn of which Malthus wrote), the balance of evidence is in favor of the Kremerian model.

Looking the other way, there is a clearly observed trend that birth rates tend to decrease with increasing affluence, though the exact mechanisms driving this pattern are not clear. I wonder if degrowth advocates anticipate that increasing birth rates would be a consequence of the policies they promote, and if so, if they intend to pair degrowth with coercive population control.

Regarding energy efficiency, improved efficiency can manifest itself in many ways, including reduced consumption, increased use of the product, or the expenditure of the energy saved on other things. The tendency for actual energy consumption to decrease by less than what would be suggested from mere efficiency increase has been called the rebound effect. The magnitude of this effect, the mechanisms that drive it, and the factors that govern its strength are all matters of ongoing research, but the evidence is that at least half of the energy savings expected by efficiency are taken back through increased consumption, either on the product that is more efficient or on others. This manifests itself as an improvement in GDP, and so there is a feedback between efficiency and GDP/capita.

Although less well-established, there is evidence of a rebound effect also resulting from clean energy deployment. For example, deployment of rooftop solar panels might result in increased energy consumption rather than merely a displacement of other energy sources. Thus the emissions intensity of energy would also have a feedback on GDP per capita.

But perhaps the most important interdependency is the effect that wealth has on technology and environmental quality. A linear relationship between wealth and environmental impact is contradicted by a large volume of empirical evidence.

Instead, a commonly observed pattern is the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC). Under this pattern, a negative impact increases with wealth up to a point, and beyond that level of wealth, the impact decreases. EKCs have been observed with many forms of air and water pollution and with deforestation. There is furthermore evidence that that the wealth-impact relationship is not merely masked by trade liberalization. While EKCs are commonly observed, they have not yet been clearly demonstrated with carbon dioxide emissions, though I see little reason to suppose that they won’t be eventually.

Let us ask consider, then, a hypothetical scenario where governments agree that, to combat global warming, they will institute a population control plan. Let us furthermore overlook the horrific human rights implications that such policies have had in e.g. China and India and the destruction to those countries’ long-term economic potential, and simply consider the impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Suppose the policy will, after a given time, result in a world population level 5% lower than what the level would be in the counterfactual. A naive application of I=PAT or the Kaya Identity suggests that greenhouse gas emissions would also be reduced by 5%. This policy would also reduce per-capita wealth under the Kremerian hypothesis, which would increase the GHG reduction. But building a clean energy system will require large investments in research, development, and deployment of new technology, and the capacity to do so will be curtailed by diminished economic prospects. So the actual GHG reduction will probably not be 5%; in fact, I would doubt that there will be any reduction at all.

Such is the distinction between environmentalism and ecologism. Environmentalism seeks to reduce pollution, biodiversity loss, and generally improve the quality of the nonhuman environment. Ecologism is a form of environmentalism that believes that the way to protect the environment is to curtail human numbers and well-being. One can embrace environmentalism and reject ecologism, but the problem is that assumptions about wealth and population are so deeply embedded in the environmental movement that it is difficult to do so. I=PAT is a mathematical formalism that gives these assumptions a veneer of rigor. Paul Ehrlich’s abuse of mathematics in this manner was called out by Neal Koblitz back in 1981.

I was recently asked, if I reject population control as a tolerable policy, how would I intend to address environmental problems resulting from overpopulation. I responded by rejecting the premise of the question. Yes, of course there are theoretical limits to how many people can live in the universe, at least under present understanding of the laws of physics. But the more relevant question is, is there a danger of overpopulation under plausible scenarios and in a time frame that is relevant to policymaking, and I would contend that there is not.

The problem with the ecologic assumptions goes far beyond abuse of mathematics. A deeper problem is that, while degrowth and population control are widespread beliefs in the environmental movement, most environmentalists are reluctant to talk about these things explicitly because … well, I don’t have to explain why, and so they talk about these things in a roundabout way that comes across as dishonest. When, for instance, population control organizations talk about “women’s rights” as a way of “solving our biggest environmental problems”, it is hard to believe that they really care about women’s rights. Or when environmental organizations call for expansive use of the precautionary principle, such as against deep sea mining, one wonders if it really about protecting ecosystems or if it is a backdoor for degrowth.

If we regard the founding of the modern environmental movement to be around the original Earth Day in 1970, then by now most of the founders have passed from the scene or are not far from doing so. I am still hopeful that this will be an occasion to get on with the vital work of improving the environment while shedding bad, legacy assumptions.

Quick Hits

Dietrich Vollrath has argued, convincingly in my view, that artificial intelligence will not lead to the explosive economic growth that some advocates are hoping for. See also Matt Clancy’s brief response and an extended debate in Asterisk Magazine.

Since last year, Pakistan has been in a state of serious economic crisis. See this article from a couple months ago for an explanation of what is going on. This older article from the Council on Foreign Relations goes into more detail about Pakistan’s international debts.

Wilson Beaver wrote an editorial today on The Hill about how to provide an adequate defense without increasing the defense budget, with under President Biden’s budget looks like will be the case.

“Looking the other way, there is a clearly observed trend that birth rates tend to decrease with increasing affluence, though the exact mechanisms driving this pattern are not clear.”

Just saw this today in case you’re interested… https://akjournals.com/view/journals/2055/aop/article-10.1556-2055.2022.00028/article-10.1556-2055.2022.00028.xml