Good evening. This week, the Energy Institute released the 2023 edition of the Statistical Review of World Energy, and today we are going to look at a few highlights. The Statistical Review is a premier source of information about the world energy picture. The product was maintained by BP from 1951 to 2022; this is the first year that the Energy Institute has released a Statistical Review. Despite the change in management, the product is very similar and the data is continuous with past releases. The Energy Institute is a professional society of engineers and other specialists in energy.

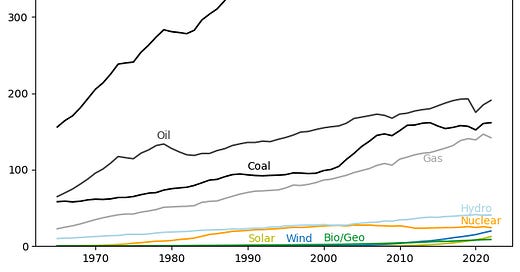

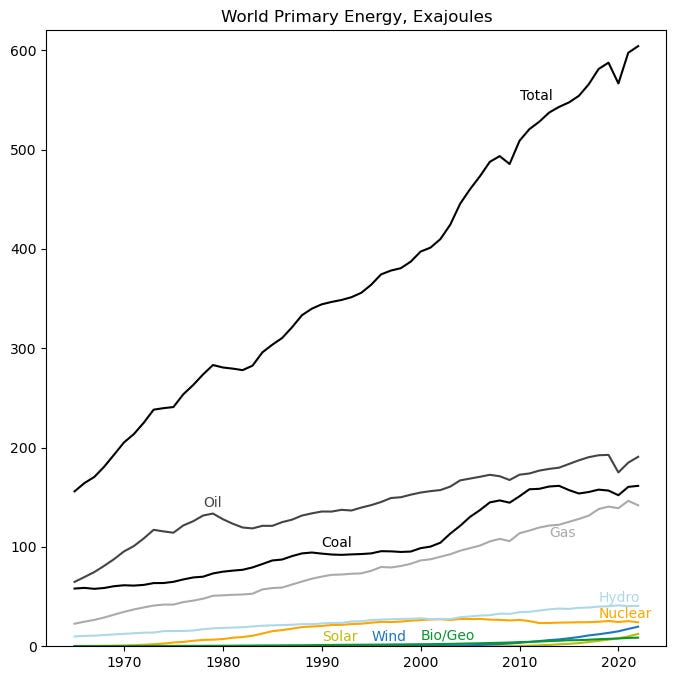

The world primary energy picture is as follows.

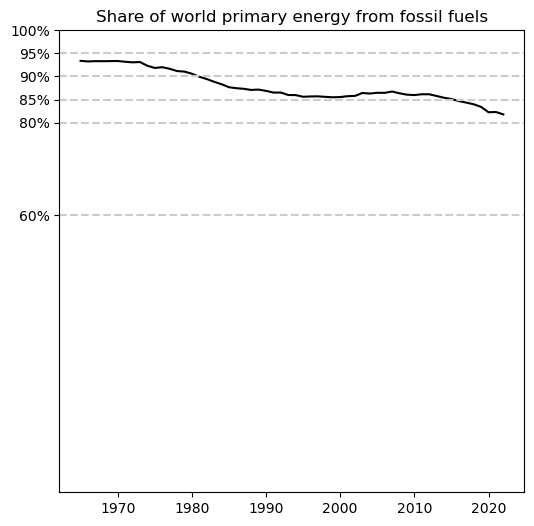

As is clear above, despite the impressive growth of wind and solar power in recent years, fossil fuels are still the dominant constituent of the world energy system. As of 2022, coal, oil, and gas together comprised 82% of world primary energy.

The share was about 86% in 2012 and 82% in 2022. At this rate of progress, fossil fuels will be out of the world energy system by around the year 2209.

Most credible pathways to a low-carbon energy system have two main pillars: low-carbon electricity generation and the use of electricity for most end uses (electrification).

Most low-carbon energy sources are used to produce electricity.

Based on the 2012-2022 rate of progress, which appears to be anomalously fast based on the trend since 1985, we will reach a 100% non-fossil electricity system in the year 2104.

On electrification, the world is again making progress but slower progress than we might like.

At the rate of progress observed from 2012 to 2022, we will see a 100% electricity energy system around the year 2146.

The last few years have shown impressive progress with wind power and solar power for low-carbon electricity, even as two other staple low-carbon sources—nuclear power and hydropower—are stagnating. On electrification, there have been impressive advances with lithium-ion batteries. Nevertheless, it should be clear from a cursory perusal of the data, as was clear from prior editions of the Statistical Review of World Energy, that the rate of progress is far from sufficient to build a low-carbon energy system on the time frame that many governments and NGOs say is necessary to avoid highly damaging impacts from global warming. To drive the point home, let’s see how we’re doing on greenhouse gas emissions.

For most of the climate movement, the main hope for addressing global warming in reasonable time is that advancement in low-carbon technology will continue and the rate of deployment of these technologies will accelerate to the point they displace fossil fuels from the energy system at a much faster pace than was derived above merely from extrapolating recent trends. It is far from clear that this will actually happen. As I discussed a few weeks ago, there is evidence that the trend of falling costs for three technologies considered central to climate change mitigation—solar panels, wind turbines, and lithium-ion batteries—has come to an end, though it is too early to declare definitively that this has happened.

As also I discussed a few weeks ago, if the falling costs trend were to end, the result would be fatal to the climate movement as a mass movement. That’s because the belief in perpetually falling costs allows the movement to defer consideration of difficult questions, such as creating a regulatory environmental hospitable to nuclear power, mining of minerals critical to the energy transition, and permitting reform to address NIMBY objections to solar and wind farms and transmission. If costs of solar, wind, and batteries stabilize, then the movement will be forced to confront these questions and will fracture.

So far, the rate of deployment of wind and solar power has not matched historical deployments of nuclear and hydropower, as demonstrated by Grant Chalmers, looking at the same data.

One non-climate observation is the Statistical Review offers an encouraging view on the state of the world economy, given that energy consumption is a good proxy for overall economic health. The last two years have shown a robust recovery from COVID-19-related disruptions, and energy data does not show a clear sign of global economic stagnation. Worldwide disruption from the war in Ukraine is not nearly as evident as many of us feared at this time last year.

That is enough for now, though I have only scratched the surface of what the Statistical Review of World Energy has to offer. The Review provides the same data for most large countries as well, and country trends tell many important stories that one would miss from simply the world trend. Perhaps that will be a subject for a future date. Thank you to the Energy Institute, and to BP in past years, for making this data available.

Quick Hits

Shortly after I published last week’s post on the Wagner Group, CaspianReport (Shirvan Neftchi) profiled Wagner’s activities in Africa. And Raphael Parens for War on the Rocks considered the risk of jihadi blowback from Wagner activities. It has since been announced (Wall Street Journal) that the Russian Ministry of Defense will take over Wagner’s global operations, not just their activities in Ukraine. It will be some time before the full implications of this can be understood.

A recent paper considers the urban wage premium in the United States, or the question of how more money a person might make by living in a city as opposed to a non-urban area. The paper demonstrates that the premium decreased during the study period of 1940 to 2010. It also argues that other sources tend to overestimate the wage premium because they fail to account for sorting effects. This means that while it can be demonstrated that people who live in cities make more than people who don’t, city living doesn’t necessarily cause wages to go up; some of the disparity is the result of people who make more choosing to live in cities.

Another recent paper demonstrates that Texas’ Heartbeat Act (S.B. 8) resulted in 9799 more live births between April and December 2022 than otherwise would have been the case. The law bans abortion after a heartbeat can be detected, which is around the six week mark. I had earlier said that, due to regulatory arbitrage, post-Dobbs abortion restrictions would not have a noticeable effect on the abortion rate. Apparently I was wrong about this.

Paul Graham’s new essay, How to Do Great Work, is a little on the long side, but it is very interesting and chock full of ideas that may be of use.

Earlier today, I thought that Twitter was down for a few hours. Instead there was a new rate-limiting policy put into place. It was rolled out suddenly and without explanation (at least that I saw). I don’t think there would be much value in reviewing the many problems Twitter has had in the past year, but it is clear that overall quality of the site has taken a steep dive since Elon Musk took over. It has gotten to the point where every time I share the link to my blog post on Twitter, I wonder if it will be the last time I do so.