This week, I am continuing with issues of sustainability, and for that, we will take a close look at one of the most notorious books in the history of the environmental movement: The Population Bomb by Paul and Anne Ehrlich. The book was first published in 1968; the version I read was mostly the 1968 and 1971 editions, with an afterword from 1978. I am going to make some guesses as to which material is from which edition; my apologies in advance if I guess wrong. Also, all page number references are based on the 1978 edition.

If you are familiar with the history of environmental politics, you know that this book has a reputation. Most environmentalists today don’t want to be associated with it, and it serves as an easy punching bag for critics of the movement. Today, we will examine how Ehrlich diagnoses the problem, what solutions he proposes, why his analysis is faulty, and how the legacy of the postwar population control movement is stronger than you might think.

If you aren’t too familiar with the history of environmental politics, you might be thinking, “C’mon, it can’t be that bad, can it?” Let’s find out.

The Problem, According to Ehrlich

The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.

From the very first sentences in the prologue, you know you are in for a treat.

The core thesis of the book, standing in a long line of similar arguments going back to Thomas Malthus, is that human population grows faster than the ability to provide for human needs, inevitably resulting in mass deprivation.

Ehrlich observes how medical technologies had greatly reduced the death rate in the industrial era. With that, the large families that characterized pre-industrial societies, rather than being necessary to support a stable population, were leading to rapid population increase.

It had been observed, going back to Warren Thompson in 1929, that societies tend to go through a four-phase “demographic transition” process. The pre-industrial stage is characterized by high birth and death rates; in the industrializing phase, birth rates remain high and death rates fall; in the mature industrial phase, birth rates fall, slowing down population growth; and in the post-industrial phase, population is stable with low birth and death rates.

Ehrlich mentions but dismisses the demographic transition, noting that no country at that time had achieved subreplacement birth rates without deprivation. Even Malthus, writing in 1798, observed that wealthy European countries tended to have lower birth rates than other societies, but neither author fully considered the significance of this pattern.

Like Malthus, Ehrlich discusses at length the impossibility of feeding a growing population. Unlike Malthus, Ehrlich forecasts a specific time frame—within a decade—in which mass death in inevitable. Also unlike Malthus, Ehrlich broadens the set of social and ecological problems whose root cause is overpopulation. He discusses a wide range of environmental problems that were at the forefront of the public’s attention at the time, including eutrophication from pesticides, phosphorus runoff from detergents, smog, pollution in Lake Erie, lead, and species extinction. He even connects overpopulation to various social ills such as crime, traffic congestion, and large classroom sizes.

Ecocentric vs. Anthropocentric Values

Speaking as an ecologist, Ehrlich warns that species extinction will lead to simplification of ecosystems, which raises the risk of ecological collapse. On pp. 43-44, he talks about how he is not going to talk about the valuation of nature for its own sake, or what other authors have termed an ecocentric view of nature. This is opposed to an anthropocentric view of nature, which constitutes the the rest of the book, that ecological thinking is called for because it is good for human well-being.

Like all broad ideas, the true origins of ecocentrism are lost to the misty recesses of time, but the concept is often credited to the conversationist Aldo Leopold in A Sand County Almanac in 1949.

A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.

With what may come across as an arrogant moralism, Ehrlich does not believe that most people are capable of showing ethical concern toward nonhuman nature, and therefore the only way to be taken seriously is to express his concerns in anthropocentric terms. This is a fairly common pattern in ecologic policy advocacy, particularly around wildlife conservation, and it bothers me for several reasons.

First, it is a dim view of humanity that does not give the general public enough credit. There are plenty of policies in existence around nature conservation, animal cruelty, and so forth that do not have obvious utility to humans. Whether these policies are sufficient is another question, but it cannot be said that the general public is incapable of caring about nature for its own sake.

Second, honesty it critical, and dishonesty, especially about one’s intentions in advocating a policy, will be noticed and not looked upon kindly. It makes a person wonder, when they hear the reasons for a proposal, what the real reasons are and why they are not stated forthrightly.

Existential Risk

Ehrlich does not use the term “existential risk”, but there are two points in the book that are of interest from the standpoint of XR thinking within the effective altruism community.

Ehrlich presents a rather unnuanced view of warfare being driven primarily by population-induced resource competition. He takes a dim view of American foreign policy in particular, seeing anti-communism as nothing more than a cover for resource grabs, while saying nothing critical of the Soviet Union’s foreign policy. Warfare is, in Ehrlich’s view, another consequence of overpopulation. He argues, for instance, that Germany’s aggression under Hitler, and particularly the doctrine of Lebensraum, or living space, was driven by population pressure.

The population of Germany was 70 million in 1940 and 84 million today. Those 84 million people enjoy a far higher standard of living than in 1940, and without engaging in military conquest since 1945. As Robert Zubrin puts it, the atrocities of the 20th century were caused by people who claimed that there were resource shortages, not actual resource shortages.

According to Ehrlich, since resource pressure exacerbates the risk of conflict, overpopulation is a contributor to the threat of thermonuclear war. He alludes to nuclear winter, a theme that he and coauthors developed in a 1985 book, The Cold and the Dark: The World After Nuclear War. As I discussed before, the nuclear winter hypothesis has deep flaws, and I greatly doubt that nuclear war poses an existential threat to humanity.

The risk of a global pandemic is yet another ill of overpopulation, according to Erhlich. Starting from p. 62, Ehrlich presents a fictional scenario in which Lassa fever explodes into a pandemic that kills billions of people. A higher population increases the number of points at which an epidemic disease can enter society and the number of human-human interactions which can spread the disease. Such anxieties persist to the present day. Spernovasilis et al. (2021) write,

In conclusion, epidemics and pandemics seem to be fuelled by human overpopulation and the elicited disruption of the balance between humankind and nature. If action is not taken to address the various factors that affect this balance, the COVID-19 pandemic will probably be just the beginning of many more to come.

The Strained Relationship with Christianity

Thomas Malthus was a clergyman, and for him there were two facets of the Malthusian crisis: “misery and vice”. Misery is the more familiar form of the Malthusian crisis: human numbers must be checked by starvation, war, or disease. Vice is the less familiar but equally serious crisis in Malthus’ conception. Since Malthus considered it morally normative for people to marry at a young age, human numbers might be checked by people not marrying and having children, a socially degenerate outcome.

No such concept of vice is found in The Population Bomb. Ehrlich portrays having more than two children as a grossly irresponsible act (in case you’re curious, Paul and Anne have one child and Malthus had three).

The book endorses Lynn White’s 1967 The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis, which blames the Christian conception of human dominion over nature for environmental problems. Ehrlich instead points to the New Age spirituality that was in vogue at the time, loosely based on Eastern religious traditions, with an emphasis on a circular conception of history without “progress” rather than linear conception, and a pantheistic relationship between humans and non-human nature.

Starting on p. 136, Ehrlich heaps particular scorn on Pope Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae, which reiterate the Catholic Church’s opposition to birth control. The Church’s position on birth control, which has not changed to this day as Ehrlich had hoped, has been a controversial subject among the Church’s members.

There is no inherent reason for Christianity and environmentalism to be at odds. Despite flaws, Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato si’ shows how an environmentalism rooted in Christian values can function.

The Solution, According to Ehrlich

There is no subtlety about it. According to Ehrlich, the only real solution to minimizing catastrophe—avoiding it entirely is no longer possible—is population control. Before we get into the specifics, in this book, “population control” might not mean exactly what you think it means. Ehrlich’s use of the term is broad, and it refers to any effort, coercive or otherwise, to reduce birth rates.

He advocates equal pay for men and women (pp. 134-135) in the hopes that better job opportunities will encourage women to have fewer children. He praises the sexual revolution of the 1960s, particularly the cultural acceptance of birth control. He advocates extensively for legalized abortion—the first two editions of the book came shortly before Roe v. Wade—and praises Senator Bob Packwood’s (R-OR, 1969-1995) 1970 bill to legalize abortion.

Ehrlich proposes (p. 132) luxury taxes on items for childcare and endorses (p. 131-132) a plan, from Senator Packwood again, to reduce the child tax credit for the second and third children and eliminate it entirely thereafter. According to Rabin (1972), Packwood’s proposal was made with population control in mind.

High on post-1970 Earth Day activist energy, Ehrlich sees an important role for the public to change social norms. He calls for an letter writing campaign for advertisers and the media to portray large families in a negative light and small families as normative.

While Ehrlich might take a dim view of humanity as a whole, he shows remarkable faith in government to set and execute population control policies in a sound manner. He calls for the establishment of a Bureau of Population and Environment (pp. 132-133) to conduct research on the optimum population level and propose policies to achieve it. Among the tasks of the BPE would be to research a method to deliberately select the sex of a child, since there is a preference for boys over girls, and a couple with girls might keep trying until they have a boy. Quanbao, Shuzhou, and Marcus (2011) document the demographic problems that have resulted from sex-selective abortions in China after the One-Child Policy, though they are conditions that Ehrlich would likely not have considered to be problems. In a scenario on p. 75, he describes the hypothetical World Commons Control System, a United Nations agency that would have regulatory authority over population policies. I can scarcely imagine the conspiracy theories that such an organization would be the subject of.

On pp. 151-152, he “goes there” and advocates that the Indian government forcibly sterilize men with three or more children, after observing on p. 82 that such an idea might have some political and logistical problems. India reached its peak of forced sterilization during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, with 8.1 million sterilizations in 1977. By comparison, the Nazis sterilized 400,000 people over the course of their 12 year regime.

As I noted last August, there is a strong interrelationship between population control and immigration restriction. The subject of immigration does not come up directly in The Population Bomb, but Ehrlich does advocate (p. 160) joining Zero Population Growth, which would be led from 1975 to 1977 by the anti-immigration activist John Tanton, who I discussed in August. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, Ehrlich also served as an advisor to the anti-immigration Federation for American Immigration Reform.

Touching on some other topics, Ehrlich is also concerned about high resource usage and advocates what future generations might call degrowth. He is encouraged by the reporting requirements from the newly-enacted National Environmental Policy Act in the 1971 edition. He offers guarded praise for Nixon’s environmental policies. On p. 145, maybe the 1971 edition, he supports nuclear fission, fusion, and hydroelectricity with some appropriate measures to address their ecological downsides, but by the 1978 afterword on energy on pp. 212-216, he had read Amory Lovins’ Soft Energy Paths and got with the environmental program of opposition to nuclear power.

Why Ehrlich is Wrong

Obviously, the forecasts in The Population Bomb were not even close to being accurate. It is worth exploring why they were wrong because most of the problems are common to Malthusian works and continue to be repeated.

It is hard to be too quantitative because the book itself does not give many numbers. But one obvious problem is that The Population Bomb routinely underestimates the capacity of food production. Ehrlich pooh-poohs the capacity of the Green Revolution to deliver lasting yield improvements, and he argues that the pesticide requirements of the Green Revolution would cause more harm than good. Citing data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Pingali (2012) finds that

The rapid increase in agricultural output resulting from the [the Green Revolution] came from an impressive increase in yields per hectare. Between 1960 and 2000, yields for all developing countries rose 208% for wheat, 109% for rice, 157% for maize, 78% for potatoes, and 36% for cassava.

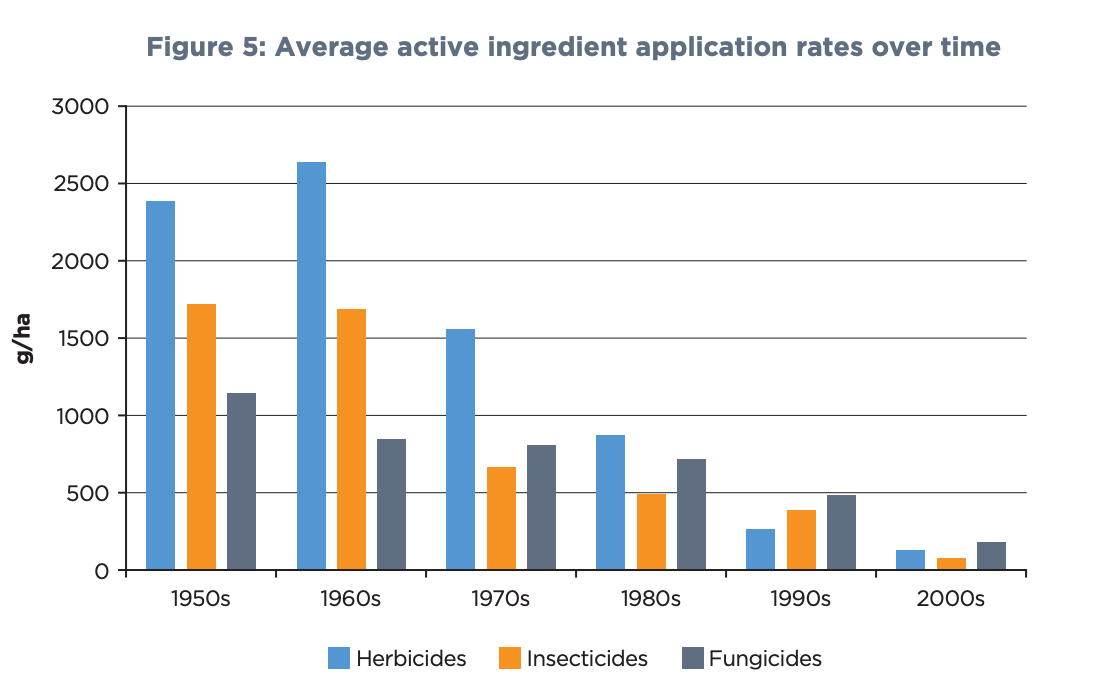

Ehrlich argued that this would require an intolerable use of pesticides. Of the top 10 pesticides by ton of active ingredient in the United States in 1968, the year of the first edition of the book, six are now banned, with the notorious DDT being banned in 1972. With improved technology, the United States requires far fewer tons of pesticides to grow food.

In the 1968 edition, Ehrlich is pessimistic that the United States will ever adopt meaningful environmental policy voluntarily, though more optimistic by 1971 after some highly productive years for environmental legislation. On leaded gasoline, which Ehrlich rightly identifies as a health and environmental atrocity, the peak in grams of lead per gallon of gasoline occurred in 1969, a year after the first edition, and a phaseout began in the 1970s, culminating in a complete ban by 1996, as Newell and Rogers (2003) document for Resources for the Future. Banning of the most harmful pesticides occurred as noted above.

Those who remember the 1970s will remember how bad smog in Los Angeles used to be. Ehrlich identifies smog as another intractable problem with overpopulation as the root cause. According to the EPA, aggregate emissions of six common air pollutants dropped by 78% from 1970 to 2021, and vehicle miles travelled nearly tripled over the same period.

I could go on and on, but I think the picture is clear. Obviously, not all environmental problems are solved. On the most prominent environmental issue of our time, which Erhlich refers to as the “greenhouse effect” with the quotation marks, emissions have roughly doubled from 1968 to 2023. Opponents of nuclear power have helped increase emissions. Still, there are plenty of solutions on the table that do not involve population control, degrowth, or dismantling capitalism.

There is every reason to believe that new and existing technology, used wisely with the right moral grounding and probably some regulation, will solve the climate change problem and other ecological problems of our time. This requires innovation, which requires a culture that respects freedom and human potential. On pp. 139-140, Ehrlich gives the opposite vision.

The Rienows estimate that each American baby will consume in a 70-year life span, directly or indirectly: 26 million gallons of water, 21 thousand gallons of gasoline, 10 thousand pounds of meat, 28 thousand pounds of milk and cream, $5,000 to $8,000 in school building materials, $6,300 worth of clothing, and $7,000 worth of furniture. It's not a baby, it's Superconsumer!

That the baby will also grow up to be a producer of these goods, and that s/he might become a scientist who will contribute to the solutions to these myriad problems, are not ideas that Ehrlich considers. His view on human potential is strictly negative. On p. 152, Ehrlich sounds like the villain of a bad movie.

I wish I could offer you some sugarcoated solutions, but I'm afraid the time for them is long gone. A cancer is an uncontrolled multiplication of cells; the population explosion is an uncontrolled multiplication of people. Treating only the symptoms of cancer may make the victim more comfortable at first, but eventually he dies -often horribly. A similar fate awaits a world with a population explosion if only the symptoms are treated. We must shift our efforts from treatment of the symptoms to the cutting out of the cancer. The operation will demand many apparently brutal and heartless decisions. The pain may be intense. But the disease is so far advanced that only with radical surgery does the patient have a chance of survival.

Ehrlich sees no instrumental value for human beings, and he certainly sees no intrinsic value. He doesn’t go into any serious discussion of population ethics, but he does comment, on the ethics of abortion,

Biologists must point out that contraception is for many reasons more desirable than abortion. But they must also point out that in many cases abortion is much more desirable than childbirth. Above all, biologists must take the side of the hungry billions of living human beings today and tomorrow, not the side of potential human beings.

The intrinsic ethical value of bringing new life into the world is a deep question that is foundational in population ethics, which I discussed a while ago. It is no surprise that Ehrlich has an easy answer to a difficult philosophical question that neatly fits the rest of the argument.

There are certain issues for which Ehrlich does not have a clear answer, such as the environmental effect of supersonic flight, which was a hot-button issue at the time and banned overland in the United States in 1973. He turns uncertainty into a strength by making an argument that would later be formulated as the precautionary principle; uncertainty over the impact of supersonic flight is reason to ban it. Then on p. 35, he argues that various unknown combinations of pesticides, radioisotopes, and detergents in the environment might cause cancer in ways not yet known. The precautionary principle is sensible to a point—a degree of risk aversion is appropriate when considering major environmental issues—but it cannot be taken to the extreme. Those who argue that something is dangerous have to give at least some plausible reason to justify their fears, lest they devolve into fearmongering.

If one wants to solve a difficult problem, then one typically breaks the problem into smaller, manageable pieces. Conversely, if one doesn’t want to solve a problem, then they can bundle several tractable problems into a single, amorphous, seemingly intractable problems. This rhetorical technique of problem bundling is especially common in ecologic works, since it derives from a basic principle of ecology. As Barry Commoner, a luminary of the early environmental movement, said in The Closing Circle (bold added by me),

All this results from a simple fact about ecosystems—everything is connected to everything else: the system is stabilized by its dynamic self-compensating properties; those same properties, if overstressed, can lead to a dramatic collapse; the complexity of the ecological network and its intrinsic rate of turnover determine how much it can be stressed, and for how long, without collapsing; the ecological network is an amplifier, so that a small perturbation in one network may have large, distant, long-delayed effects.

Incidentally, Commoner was a staunch critic of Ehrlich’s emphasis on population.

To summarize, Ehrlich vastly underestimates the potential of new technology, and he writes in a sensationalist manner that violates David MacKay’s dictum, “numbers, not adjectives”. It is quite clear that he wrote from ideology, not from a good-faith attempt to accurately portray the subject under discussion. No wonder the forecasts were so far off.

Before we wrap up this section, let us note a non-reason that Ehrlich was wrong, and that is the erroneous notion that falling birth rates, achieved by noncoercive population control, have in fact achieved what Ehrlich desired. In the 1978 update on p. 204, based on then-recent demographic data, Ehrlich projects that the United States would peak in population in the year 2025 at 250 million people. According to the Census Bureau, population in the United States was 340 million in 2024, with a projected peak in 2080 at 369 million, though granted I would not take too seriously a projection so far in the future. Foreign born population was 9.7 million in 1970 and 46 million in 2022; I suspect that the increase in immigration and their US-born children explains most of the difference between Ehrlich’s forecast and reality. Note that the aforementioned environmental improvements occurred despite, or maybe because of, population growth.

World population was about 3.5 billion in 1968 and around 8.2 billion today, or more than twice the 1968 value which Ehrlich characterized as too many. And yet by most material metrics, the world average standard of living is better today than ever before.

Paul Ehrlich’s forecast in The Population Bomb was comically wrong, virulently misanthropic, and inspirational to some of the worst atrocities of the 20th century. You might think that this, as well as the fact that birth rates that have fallen across much of the world, especially wealthy countries, into subreplacement levels, would have thoroughly discredited the overpopulation scare. You would be wrong.

The Enduring Legacy of Population Control

Unless you remember the 1960s and 1970s, or you have read a lot of history of the environmental movement, it is hard to appreciate the centrality of population anxiety to the environmental thinking of that time. That anxiety is dormant now, not gone, and it may be coming back to life.

It is widely held in mainstream intellectual circles, and almost universally held in the environmental community, that the lower the birth rate, the better. Here, for instance, Max Roser offers a fairly standard account of contemporary understanding on fertility with an unmitigated antinatalist tone. Petchesky (1995) observes that the shift in language of international NGO work on childbearing from population control to womens’ autonomy may have been more rhetorical than substantive. More than 14,000 scientists signed Ripple et al. (2021), warning of a “climate emergency”, which includes population control—with the flowery language of “stabilizing and gradually reducing the population by providing voluntary family planning and supporting education and rights for all girls and young women”—as a solution.

Population control, or at least ideas closely adjacent to that, are embedded deeply in American politics and society. Legalized abortion and immigration restriction, two ideas closely associated with the postwar population control movement, are more popular today than ever. Almost all cities have zoning codes and many have urban containment policies, generally popular policies that are localized population control measures. Casual expressions that there are “too many people” in one’s area are common, even if the speaker does not understand the nature of these sentiments.

Most of all, whether for ideological, economic, or cultural reasons, the general public around the world is acting out antinatalism by having few kids or none at all. Until there exists a deep and broad pronatalist movement—and as I wrote last year, the one that exists now has its own set of problems—the followers of Malthus will rule the day, and the social ills they bring will persist.

The 1968 edition said that the famines were inevitable in the 1970s - the 1980s reference was added to the later editions (with of course no acknowledgment by Ehrlich of the change). Why the change? Let’s just say that Borlaug’s Green Revolution had taken off with the result India was exporting grain rather than importing it.